In the early autumn of 1800, an odd couple showed up in Felpham, a small village on England’s West Sussex coast: the printer, artist, poet and general-purpose visionary William Blake (1757-1827), with spiky red hair and eyes burning like that of the tiger he conjured in a poem, and Catherine (“Kate”) Blake, his wife and intrepid assistant, always ready to take a dip in the sea when the opportunity arose. “It was a shock for the villagers” when they arrived, notes the biographer and critic Philip Hoare in William Blake and the Sea Monsters of Love, a gloriously unclassifiable book, “like discovering new age hippies had moved in overnight”.

The Blakes, the soot of London still clinging to their clothes, had never seen an ocean before. In the salty air, the tangy water, they tasted a new kind of freedom that, Hoare argues, manifested itself in their work, too. In Blake’s hallucinatory poem Milton, written and illustrated in Felpham, the poet of Paradise Lost descends from the skies to save a world overshadowed by “dark Satanic mills”, beholden to the laws of mechanics, not those of the spirit. In one of his illustrations, Blake drew himself strolling outside his Felpham cottage while an angel hovered over him in the trees, looking, Hoare quips, “like a blown-in plastic bag”.

Tossed ashore

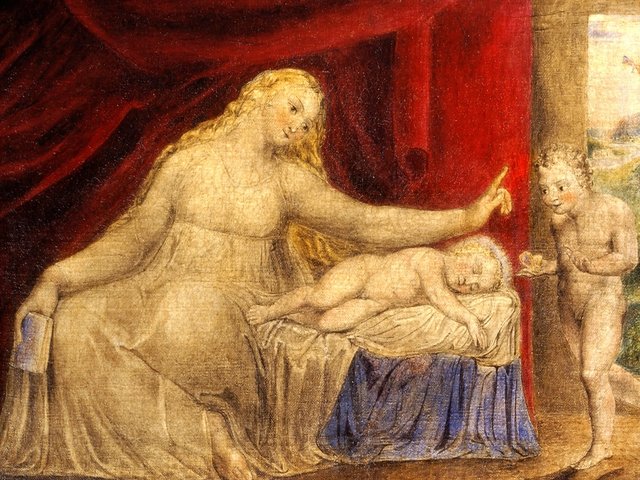

Blake later referred to the three years he spent in Felpham as his “slumber on the banks of the ocean”. But he was in fact wide awake while he was there: “My Eyes more & more / Like a Sea without shore / Continue Expanding”, he wrote to a friend. Hoare, an ocean enthusiast and ferocious swimmer, who has devoted several books to the topic, including the prize-winning Leviathan or, The Whale (2009), knows precisely what Blake was talking about. Humans are “what the sea leaves behind”, Hoare states—underwater debris tossed ashore to struggle and rot. But in our imagination, in poems and paintings, we can return to what we have lost. The androgynous figures in Blake’s prints—Michelangelo-esque sculptures freed from the stone, lovely bodies flying, lying, writhing, their long limbs stretched, spread or bent—drift through a fantastical world as fluid as the sea. There are, of course, stunted forms of life here, too: Blake’s Newton (around 1795-1805) portrays the discoverer of universal gravity, the embodiment of Satanic reason, sitting on a mossy rock at the bottom of the sea, compass in hand, still drawing his geometric figures.

Other Blake works are less poignant than horrifying. In the miniature The Ghost of a Flea (around 1819-20), for example, a scaly, reptilian thing ambles away, holding a cup filled with blood. Blake’s imaginings are, claims Hoare, visceral experiences, action paintings of sorts, and they do not even need colour for effect. Take Illustrations of the Book of Job (1825), where the words wreathed around Blake’s depictions of Job’s trials (in which Blake recognised his own) leap off the page as if they were, in Hoare’s inspired analogy, the inter-titles in a silent movie.

‘Real and weird’ characters

William Blake and the Sea Monsters of Love is Hoare’s version of a Blake print, a meandering, undulating reverie conjuring a procession of characters both real and weird: lovers of Blake and lovers of the ocean; the poet-priest Gerard Manley Hopkins; the novelist-seafarer Herman Melville; the artist-photographer Paul Nash; the writer-philosopher Iris Murdoch; the archaeologist and soldier T.E. Lawrence. These are Hoare’s sea monsters, queer, amphibious rebels against dry orthodoxy, set on this planet to remind us that rules are there to be broken. Hoare admits to a particular infatuation with the writer-activist Nancy Cunard (1896-1965), whose elongated body could have been drawn by Blake—ethereal and pale to the point of abstraction while still unsettlingly feral: “an egret ready to strike”, a grass snake, with fingers shaped like a crab’s claws. Milton was Blake’s guardian angel; the “ivory-armed” Cunard is Hoare’s. He hung her portrait on a wall of his London apartment.

Some readers might surrender before the sheer volume of detail Hoare lobs at them. Like Melville’s Ishmael, he has swum through libraries, and he lets you know about it: you will hear about every outrageous costume Lawrence ever donned, or the number of bracelets Cunard wore (12). But that is perfectly OK: William Blake and the Sea Monsters of Love is a book to dive into and get lost in; you might find a new world while you are at it. If Blake was, as Hoare has it, the “Willy Wonka of art”, Hoare is our Charlie Bucket of criticism. To me, one of the most powerful moments comes at the end of the book when, on a dark, overcast day in Cambridge, a librarian at the Fitzwilliam Museum hands Hoare his hero’s steel-rimmed glasses, 3.50 dioptres on the left, 3.25 on the right, with convenient loops at the ends. As Hoare lifts Blake’s specs up to his eyes, the sun bursts through the window, as if to confirm what his book has already proven: “I am seeing what he could see.”

• Philip Hoare, William Blake and the Sea Monsters of Love, published 10 April by Fourth Estate, 304pp, 16 pages of colour illustrations, £22 (hb)