Six-hundred-year-old stone carvings have been revealed on a beach on the island of Oahu in Hawaii. The petroglyphs were found just outside Waianae and represent people and abstract symbols carved into the rock by ancient Hawaiians. Although the petroglyphs had already been discovered in 2016, the symbols are usually hidden by sand and will only stay uncovered for a short time.

“Seasonal changes in tide and wave energy have shifted the sands along the beach and fully exposed these petroglyphs,” Dave Crowley, manager of US Army Garrison Hawaii’s Cultural Resources Management Program (CRMP), said in a statement. “This is the first time since 2016 that the entire panel has been visible.”

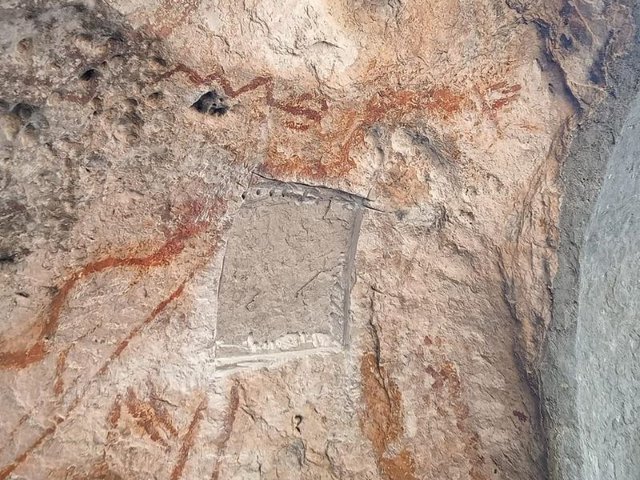

Of the 26 carvings, 18 appear to represent humans etched as stick figures, while others take more abstract forms. The carvings range in size between 15cm and more than 2m. They are spread across a 35m-long sandstone panel stretching along the beach at Pililaau Army Recreation Center.

“The ones with the fingers, for me, are pretty unique,” army archaeologist Alton Exzabe said in a statement after the initial discovery in 2016. “I believe there are some elsewhere with fingers, but fingers and hands are pretty distinct, as well as the size of them. We find a lot of petroglyphs that are a foot or so tall, but this one measures 4-5 feet from head to toe. It’s pretty impressive.”

Because ancient Hawaiians carved these symbols directly into the rock, it is hard for archaeologists to date precisely when they were made. “While it is difficult to pin down an exact date, these could potential be upwards of 600 years old, based on nearby sites,” Laura Gilda, principal archaeologist for CRMP, said in a statement. “We documented them to share with the community while keeping them safe.”

Identifying the Hawaiian petroglyphs’ function is just as difficult as dating them. “Undoubtedly, they had different functions in different places,” Patrick V. Kirch, an historical anthropologist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, tells The Art Newspaper. “This is pure speculation on my part, but given the beach context, these petroglyphs might have been carved to memorialise the arrival of a group of people—voyagers from another island perhaps?”

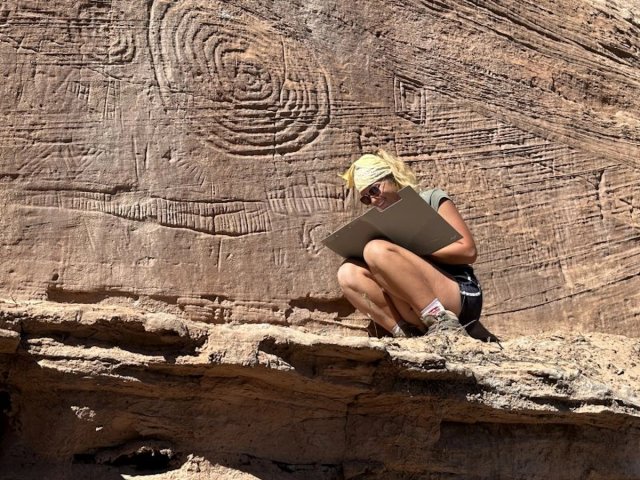

Ancient Hawaiian petroglyphs revealed at Pililaau Army Recreation Center, 12 July 2025 Photo: Nathan Wilkes, courtesy US Army

The recently uncovered carvings are just a few of Hawaii’s many ancient petroglyphs. On the Big Island alone, thousands are etched into the lava rock at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, with others at Puakō Petroglyph Archaeological Preserve and Kaloko-Honokōhau National Historical Park. Hawaiian-style petroglyphs have even been found on a beach on Foa Island, Tonga, 5,000km southwest of Hawaii.

Petroglyphs occur on every island in Hawaii, with more than 24,000 individual glyphs known, says the archaeologist Mark D. McCoy of Florida State University in Tallahassee. “The first attempt to inventory them highlighted 135 sites, but more have been found,” he adds. “I expect more will be discovered, but we probably have a good idea where the largest panels of images are. We also have a good idea of the range of types of images that were inscribed into stone—people, animals, events and abstract forms.”

Ancient Hawaiian artists used stone tools to etch or peck their carvings, and to scrape images into rocks. Their petroglyphs often represent humans, sometimes as stick figures carrying objects like fishhooks and clubs, but there are also spirits, animals (particularly dogs), the sails of canoes and geometric shapes.

“Like all art, their meaning and function is subjective and open to interpretation,” McCoy says. “There are few that have broadly known oral traditions associated with them that give us the cultural and historical context in which to narrowly interpret them. One example that we can be specific about is that people pecked grid patterns of small holes to make boards (papamū) for the game Kōnane.”

The shifting beach sands will soon reclaim the ancient petroglyphs at Pililaau Army Recreation Center, obscuring them from view and protecting them from damage.

“Stewarding these lands is vital to our mission,” Crowley said in a statement. “By protecting cultural sites like these petroglyphs, we honour Hawaii’s heritage, build stronger community ties.”