A poetic lament for a squirrel called Jack, which lived along with its would-be regicidal owner in one of the most famous psychiatric hospitals in the world, will go on display for the first time this week at the Bethlem archives, alongside several other previously unseen works.

Bethlem Royal Hospital, founded in 1247 and after several moves now located on the outer edge of south east London, was the original Bedlam, and claims the title of the oldest psychiatric hospital in the world. However, it also has a remarkable art collection created by former patients and by artists dealing with the subject of mental health, with regular public exhibitions in its own dedicated museum building: the Bethlem Museum of the Mind.

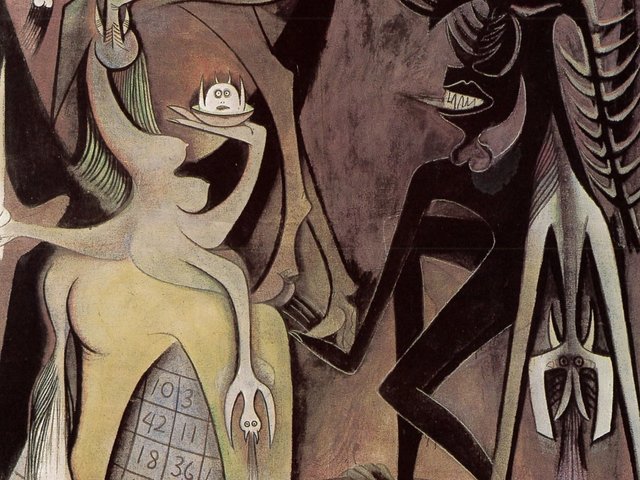

The latest, opening on 14 August, is Between Sleeping and Waking: Hospital Dreams and Visions, which includes many works by former patients and a major installation, Night Tides, by the contemporary artist Kate McDonnell.

James Hadfield and Jack the squirrel were both confined for life to Bethlem in the early 19th century, Jack as a pet, and Hadfield after attempting to assassinate George III during a performance at Drury Lane theatre. Hadfield, who had been seriously injured during his time as a soldier, was in the grip of religious mania and had become convinced that he could only save England by being executed by the authorities.

On 15 May 1800, when the king stood up in the royal box for the national anthem, Hadfield fired a pistol, but missed. According to a contemporary account of his trial, “great consternation ensued and he was thrown over the rails into the orchestra and conveyed into a room under the theatre”.

His subsequent successful plea of insanity, saving him from hanging for treason, helped to establish the case law for such pleas, and certainly saved the lives of many others experiencing mental illness and accused of capital crimes.

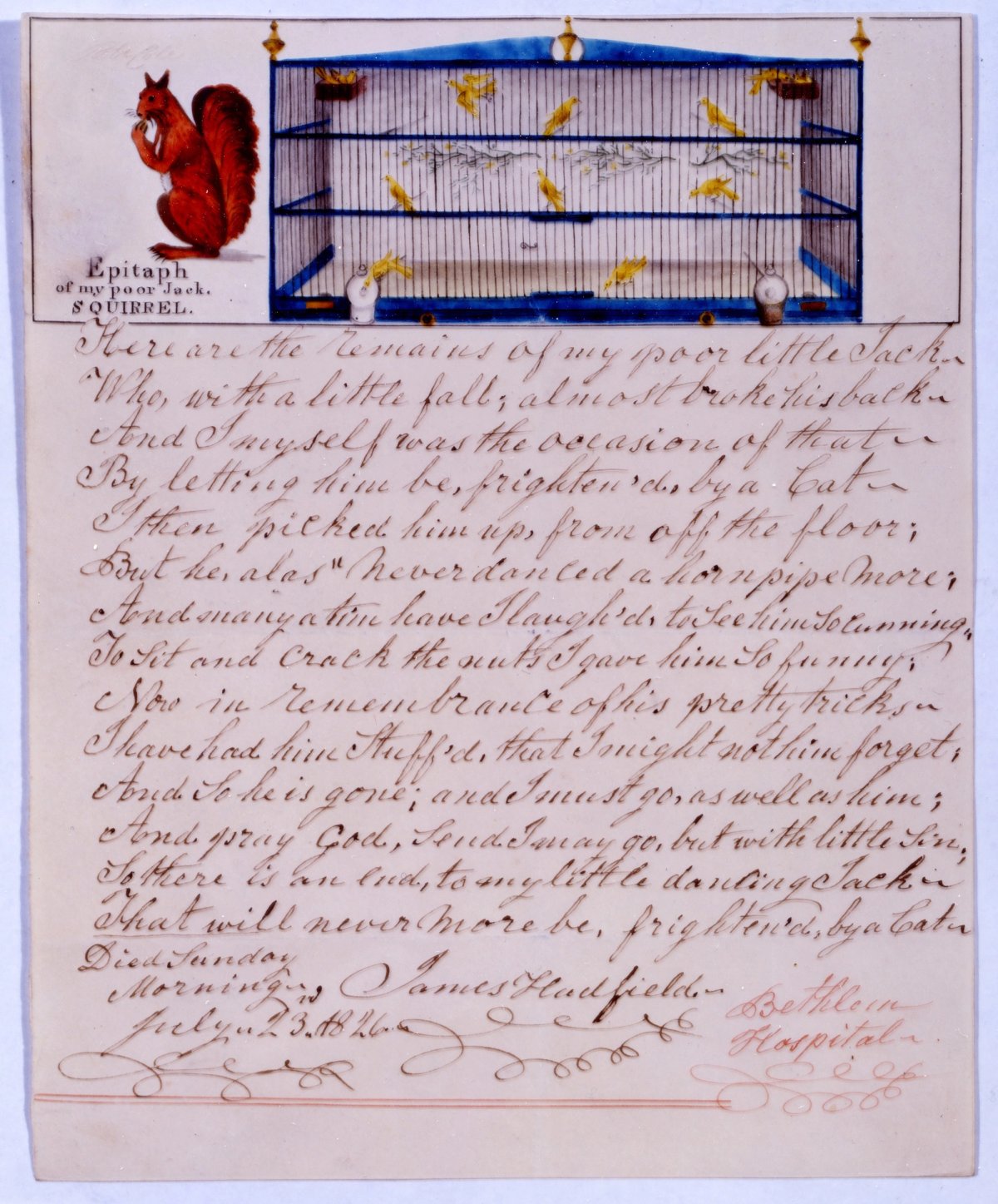

At Bethlem, where he lived until his death in 1841, Hadfield became a minor celebrity. He had many visitors to his cell, where he traded his poems and drawings about his pets for snuff and tobacco. The lament for Jack is a rare surviving example, kept in the hospital archives.

In it, Hadfield blames himself for the fate of “my little darling Jack” who “with a little fall almost broke his back, and I myself was the occasion of that, by letting him be frightened by a cat”. Mortally injured, the squirrel “alas never danced a hornpipe more”.

Jack, however, had not entirely left the building, as Hadfield recorded: “Now in remembrance of his pretty tricks, I have had him stuffed that I might not him forget.”