A 13-year drought may have played a role in the collapse of ancient Maya civilization. By analysing a stalagmite found in a Mexican cave, researchers collected climate data for the years 871 to 1021—a time of decline for Maya society. The rainfall levels revealed that the ancient population suffered through repeated periods of severe drought during what should have been wet seasons.

“What surprised us was how clearly the seasonal cycle was recorded, it’s highly unusual to be able to access past climate information at such a high-resolution,” Daniel H. James, a postdoctoral researcher at University College London, and lead author of the research paper, tells The Art Newspaper. “To be able to generate a sub-annual climate record that spans such a societally important time is a very rare and exciting opportunity.”

The reasons for the decline of Classic Maya civilization—which happened between 800 and 1000 and is sometimes referred to as the Maya collapse—have long been debated among experts. Changing trade routes, war, civil unrest, disease and severe drought have all been cited as possible contributing factors. Now, James and his colleagues have added extra evidence for the impact of droughts.

“Droughts have been proposed as a contributing or even instigating factor since the 1990s, when the first low-resolution climate evidence was published,” James says. “Our new high-resolution record refines and quantifies these earlier findings, and helps prove that drought was a part of the complex sociopolitical decline.”

The authors (from left to right) Daniel H. James, Ola Kwiecien and David Hodell install a Syp drip water autosampler in Grutas Tzabnah (Yucatán, Mexico) to analyse seasonal changes in drip chemistry. Photo: Sebastian Breitenbach, 2022

To reach their conclusions, published in the journal Science Advances, James and his colleagues studied oxygen isotopes taken from a stalagmite found in Grutas Tzabnah, a cave in the Mexican state of Yucatan. This enabled them to identify the amount of rainfall during the wet and dry seasons that coincided with the Maya decline. Their results revealed multiple periods of drought, one lasting 13 years, roughly from 929 to 942, and others for over three years.

“Through very fine sampling of a stalagmite with clear annual growth layers, we were able to trace individual past wet and dry seasons through changes in a chemical proxy that tells us about rainfall amount,” James says. “This means we can now infer the precise duration (in years) of droughts during the Maya Terminal Classic [roughly 800 to 1000]. We found many frequent droughts during this time, including one that lasted 13 consecutive years, more than any in the region’s recorded history.”

Based on archaeological evidence, during this period of decline, the Maya abandoned settlements and the centre of political power moved north. There was social and political upheaval, while uncertainty over when the rain would fall, and how much, likely caused stress among the population, helping to weaken elite power. Nonetheless, the Maya did develop methods to survive periods of drought.

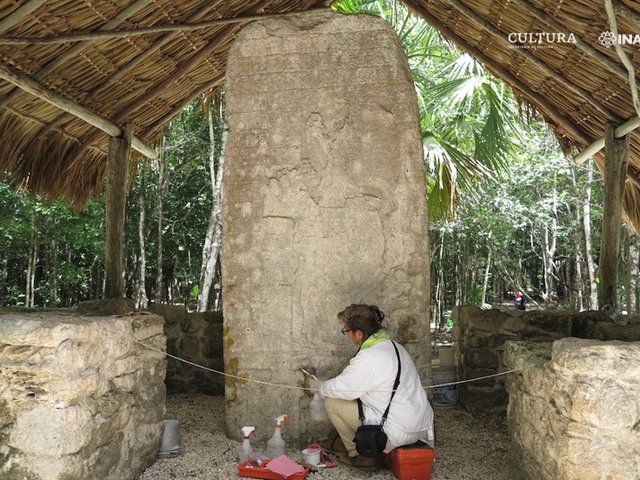

The authors (from left to right) Daniel H. James, David Hodell, Ola Kwiecien and Sebastian Breitenbach at the Maya site of Labna in the Puuc region (Yucatán, Mexico), which was most likely abandoned during the Terminal Classic. Photo: Mark Brenner, 2022

“There is extensive archaeological evidence for water storage and management at Terminal Classic Maya sites,” James says. “The population were prepared and adapted to cope with drought up to a point, but these methods could only go so far. Societal stress (like drought-induced famine) can lead to a lethal risk spiral, where cohesion and social order deteriorates after trusted methods of mitigation fail. More centralised cities like Chichén Itzá likely survived longer with increased support from their wide trade networks.”

The team’s results can now be used to enhance our understanding of what people experienced during this turbulent era in Maya history.

“What excites me most is how we can now imagine this history on a human level—13 years of wet-season drought could mean 13 consecutive failed harvests, we know from the modern world how devastating that can be,” James says. “Hopefully now this record can be compared with the individual histories of individual Maya sites, to access more of these human stories.”