This month marks the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. One of the deadliest storms in US history, it resulted in the death of an estimated 1,400 people, according to recent government figures. An ongoing group show at Ferrara Showman Gallery in New Orleans explores how the storm changed the city and the local art scene, and how artists have worked to reinvest in New Orleans in the two decades since.

The gallery celebrated the opening for This City Holds Us earlier this month on White Linen Night, New Orleans’s annual art block party. Revelers dressed in breezy summer clothes and passed through the 20 or so art galleries lining Julia Street in the city’s historic Warehouse Arts District. Around 35,000 visitors passed through that evening, says gallery founder and partner Jonathan Ferrara, many of them more engaged with the show than usual.

“That was unique,” Ferrara tells The Art Newspaper. “It was really a wonderful thing to see. It doesn't happen that often.”

The exhibition, which invited artists to revisit their experiences during and after Hurricane Katrina, may have struck a chord with the local audience. New Orleans, Louisiana’s most populous city, was the hardest hit by the category 5 storm. Within a week of its landfall on 29 August 2005, around 80% of New Orleans was underwater, in some areas as deep as 20ft, after its system of levees and floodwalls failed.

While an estimated 80% of New Orleans’s residents evacuated before the storm, thousands of the city’s most vulnerable lacked transportation or resources to follow authorities’ short-notice evacuation orders. Many sought shelter in the Louisiana Superdome, the local indoor arena. Reports of unsanitary conditions, violence, crime and even death turned the “shelter of last resort” into a symbol of the institutional failures that left New Orleans residents to suffer in the wake of Katrina. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (Fema), the government department charged with co-ordinating disaster response, was widely criticised, prompting agency-wide reforms. (This week, US media outlets reported dozens of Fema employees have been put on leave after warning in an open letter that US President Donald Trump’s cuts to the agency threaten to undo those improvements).

“We were the canary in the coal mine with regard to large-scale natural disasters,” Ferrara says. “It showed some of the inadequacies of the federal system on many different levels.”

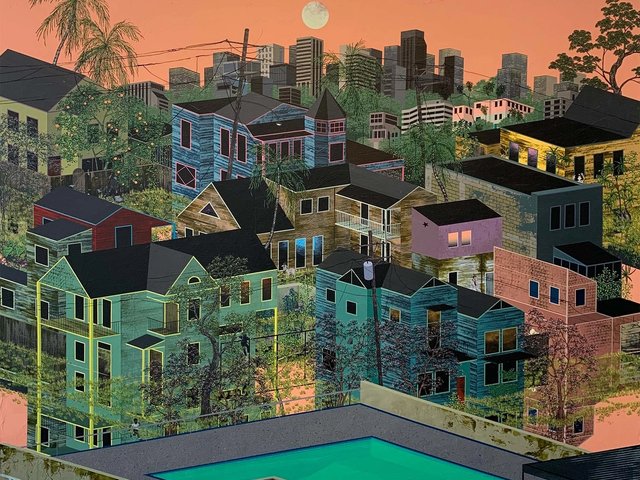

Work by artists Anastasia Pelias, Jonathan Ferrara (also the gallery's founder) and Gina Phillips. Photo by Mike Smith, courtesy Ferrara Showman Gallery

While the resilient city has made significant progress in rebuilding, recovery has been uneven—today, the population is still below pre-Katrina levels, especially in historically Black neighbourhoods like the Lower Ninth Ward, which endured some of the deadliest flooding.

When Ferrara and gallery director and partner Matthew Weldon Showman began contemplating the idea of a show dedicated to the 20th anniversary of the storm, they knew they wanted to keep the focus on the progress New Orleans and its artists have made since Katrina, not on the imagery associated with the destruction.

“What really sets us apart—and this has been the feedback from our patrons—is that we have taken on this new perspective rather than looking back,” says Showman, who curated the exhibition. “We are honouring the past, but it’s triumphant and celebratory of how far we've come, and what we have still yet to do in the city.”

'The experience is part of my makeup now and only made me stronger'

This City Holds Us features work by ten artists who were affected by Katrina. Showman had artists submit written testimonies reflecting on how the storm shaped their lives and creative practices. The multidisciplinary artist Anastasia Pelias, a New Orleans native, has several abstract paintings on display.

“I hate revisiting the trauma of Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath,” she wrote in her testimony. “The people of New Orleans were not protected by the powers that be, in this case the Army Corps of Engineers, who knew that our levees were unstable and that a disastrous event was not just a possibility, but was imminent… all of the citizens of New Orleans were betrayed, but the pointedly inequitable treatment of different demographics—people in low-income neighbourhoods—immediately became very clear. New Orleans was exposed for its great racial and socioeconomic disparities and divide.”

Katrina “shredded our entire ecosystem and infrastructure, not just in the arts, but in general”, Ferrara says. “In the beginning, artists were just trying to survive. People weren’t focused on buying art; they were rebuilding their walls.”

But slowly, from that wreckage, a starting-from-scratch mentality allowed some artists to reinvent their practices after the storm. In the wake of destruction, some drew fresh inspiration from New Orleans’s unique blend of Caribbean, French, West African and Southern cultural influences.

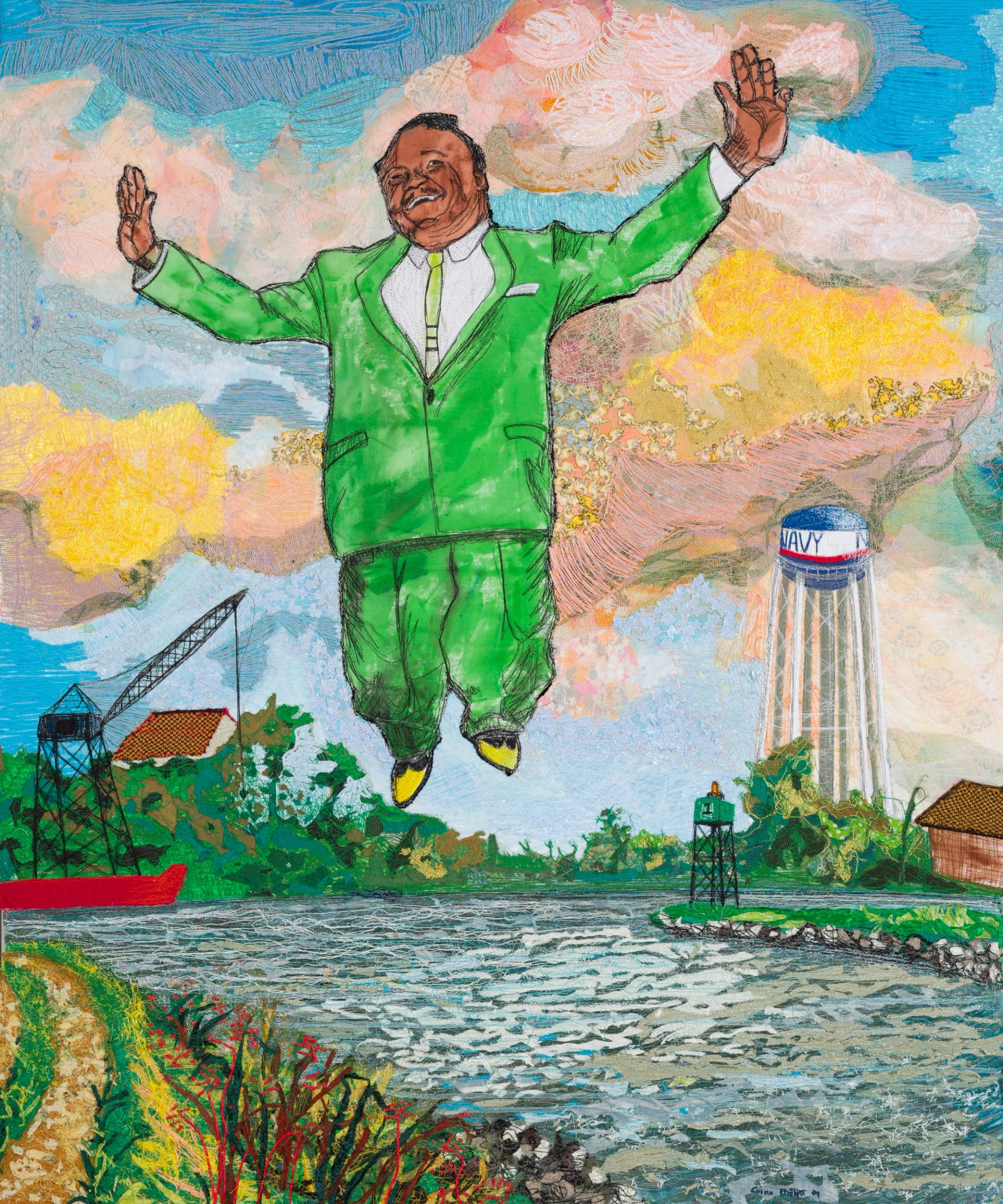

Fats Got Out (2025) by Gina Phillips Courtesy Ferrara Showman Gallery

“It was like living in a petri dish—anything was possible, nothing was probable,” Ferrara says. “The ones who stayed were zealous. They were the ones that said: ‘I’m not leaving.’ And one of the things that kept those people there was the culture, the music, the food, the art, the literature, all of those things that make New Orleans a great place.”

The mixed-media artist Gina Phillips lost nearly everything in the storm when her home studio flooded. Afterwards, she spent two years in a Fema trailer (a caravan that was supposed to be temporary shelter) and used a grant to purchase a longarm quilting machine. This tool allowed her to explore new themes—place, history, geography—in thread and fabric, inspired by New Orleans. “It’s been 20 years since Hurricane Katrina—hard to believe. Also hard to believe I’m about to say this—but I wouldn’t change anything,” Phillips wrote. “The experience is part of my makeup now and only made me stronger.”

The photographer Trenity Thomas was only six years old when he evacuated. His pictures in the exhibition show familiar New Orleans scenes, like shotgun house porches, second line street parades and the famous Café Du Monde.

Aimée Farnet Siegel, another artist featured in the show, only began her art practice after the storm. She felt inspired in the wake of Katrina, when she “found a city transformed—scarred, resilient and determined”, Siegel wrote. What struck her most were the T-shirts locals wore after Katrina. Some slogans on the shirts expressed indignation at the government’s negligence, while others used humour to poke fun at the chaos. She gathered 81 of them for another gallery show, some of which are also on display at Ferrara Showman Gallery, with sayings like “I stayed in New Orleans during Katrina, and all I got was this lousy T-shirt, a new Cadillac and a plasma TV” and “Make Levees, Not War”. Siegel later turned to painting, and three of her recent canvases are included in the exhibition. “Much like my beloved New Orleans, my work is constantly changing and evolving, carrying within it the ruins and the renaissance—proof that healing, rebuilding and flourishing are possible,” Siegel wrote.

Two paintings by Aimee Farnet Siegel, and t-shirts she collected in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Photo by Mike Smith, courtesy Ferrara Showman Gallery

Most featured artists in the show are from or based in New Orleans; only the sculptor Paul Villinski is not local. He visited shortly after Katrina in 2006 to scavenge materials for his work, often made with discarded objects. This show includes pieces made from vinyl records that Vilinski came across in the Lower Ninth Ward. The vinyl had been warped from hours sitting in the sun, the round center labels rotted away. Villinski reshaped them into birds.

“In some ways, the storm propelled the art scene here in New Orleans. The spotlight on the city and the tragedy that occurred here also invested public interest in what came of the city afterwards,” Showman says.

Ferrara and Showman credit Prospect New Orleans, the contemporary-art triennial that began in 2008 as a response to Katrina, as helping reinvigorate art in the city and even growing the art scene to beyond what it was before the storm. (Prospect’s organisers announced last month they would skip the 2027 iteration and publish an anniversary book instead. It remains to be seen if future editions of Prospect New Orleans will take place).

“The spotlight came because of Katrina, which is not necessarily what you want, but it is what it is,” Ferrara says. “We have stood up under the spotlight as an artist community.”

Other galleries and institutions across the greater New Orleans area are marking the anniversary with exhibitions as well. The New Orleans Museum of Art is hosting A Time Before Katrina (until 21 September), an exhibition of dense and richly detailed works on paper by Dapper Bruce Lafitte, an artist based in the Lower Ninth Ward. The New Orleans Academy of Fine Arts has teamed up with ArtsvilleUSA and the River Arts District Artists in Asheville, North Carolina, to put on A Tale of Two Cities (13 September-8 November), marking the anniversaries of both Hurricane Katrina and 2024’s Hurricane Helene—the deadliest storm to strike the continental US since Katrina. Meanwhile, the New Orleans African American Museum is staging a year-long show called The Katrina List: An Untold Story of Hurricane Katrina (28 August 2025-30 August 2026), bringing together survivors' testimonies, photographs, handwritten letters and salvaged objects to offer the public an interactive memorial to the human impact of the storm.

- This City Holds Us, Ferrara Showman Gallery, New Orleans, until 13 September