Leni Riefenstahl is the film-maker you love to hate. A German actress and film director celebrated in the first half of the 20th century, she helped revolutionise the art of cinema in two documentaries, Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938). In them she created exhilarating sequences shot from ascending elevators and edited together a series of high dives making athletes appear to float in midair. Yet their ultimate purpose, the glorification of Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich, made them propaganda for a genocidal regime. After the Reich fell and the war ended, she was condemned in public and shunned by the movie business.

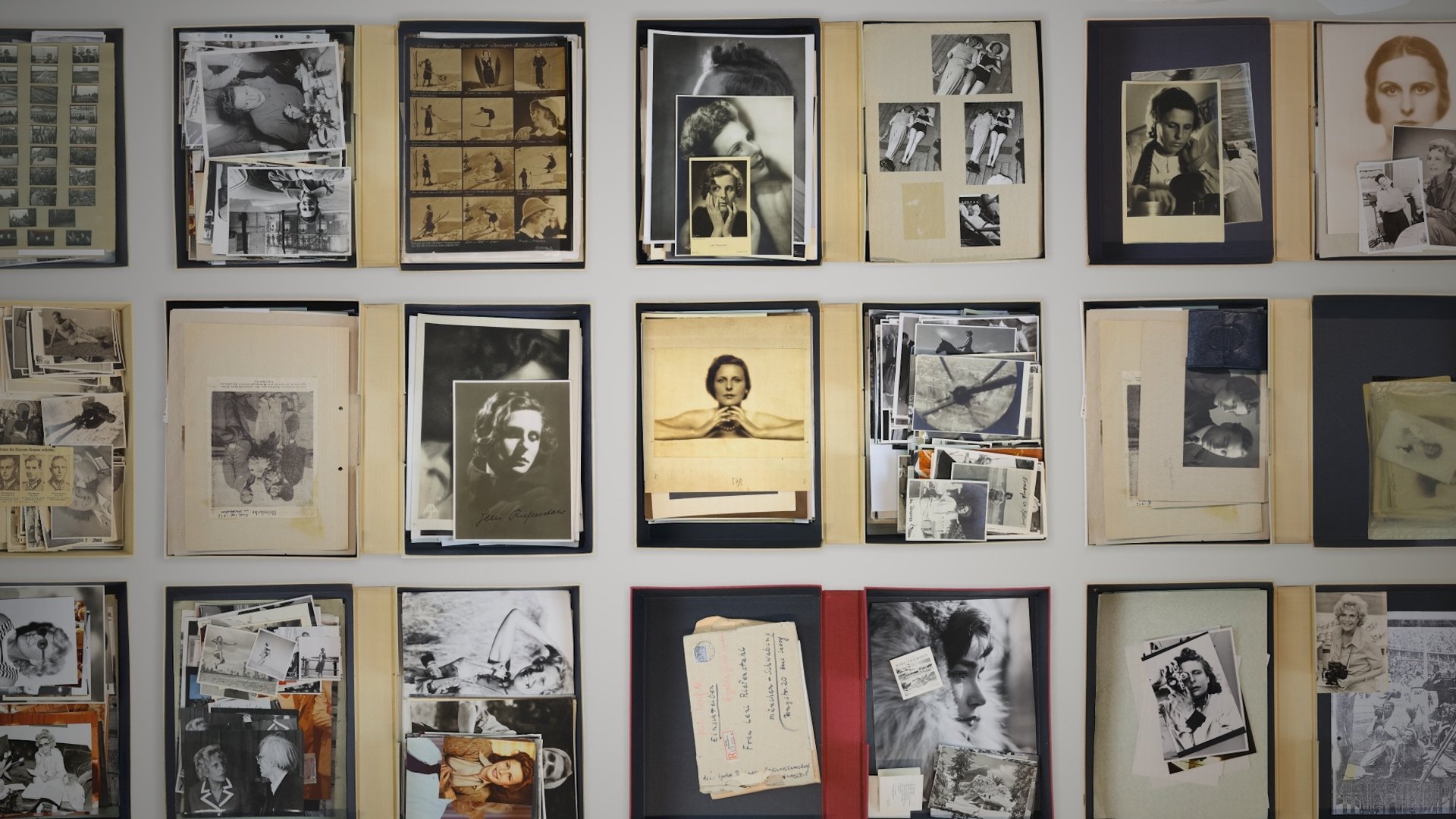

Since then, much has been written and disputed about Riefenstahl, who was born Helene Bertha Amalie in Berlin in 1902. In her late life she would enjoy occasional returns to favour; her films have been studied in university classrooms and she was honoured at the first Telluride Film Festival in 1974. Now, the new documentary Riefenstahl is being released in the US and promises a look into the personal archive she left behind after her death in 2003. While she must have reviewed its contents, the director Andres Veiel says she missed some telltale evidence. “I can’t believe she left the drafts of her autobiography around, so you see what she originally wrote and then what she corrected,” he says.

The film opens rather dreamily, with a soft-focus montage of the photogenic Riefenstahl in her acting days, footage of Nazi rallies and ribbons of black and white film. In short, we are visually introduced to her journey as an artist, the political movement she was swept up in and access to a medium of powerful persuasion.

“This is what Leni Riefenstahl stands for—to put propaganda for fascist ideology in a way that people were seduced,” says Sandra Maischberger, a veteran journalist and television host, who produced Riefenstahl. “Looking at Leni Riefenstahl is always looking at ourselves.”

The project is personal for Maischberger, too: she interviewed Riefenstahl over a two-day period in 2002, the year the film-maker turned 100. “I came out of the house, and I didn’t have any answers to my questions,” Maischberger recalls. “She was brilliantly performing to be a non-political artist.”

Materials from Leni Riefenstahl's archive © Vincent Productions

When Riefenstahl’s husband, Horst Kettner, died in 2016, Maischberger set about gaining access to the director’s archive, which had been left to the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. She asked Veiel to take on the new documentary because of his lauded 2017 film on Joseph Beuys. It took years to go through the 700 boxes and inventory the many photographs, documents and recordings contained in Riefenstahl’s archive, then another 18 months to edit. The film highlights little-known details of Riefenstahl’s life, such as her childhood with a dictatorial father, as well as photographs of personal meetings with Hitler and Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Party’s chief propagandist. The documentary also uses clips from her own films and past television interviews.

What is not in dispute is that Riefenstahl fell under Hitler’s spell. In 1932 she heard him speak at a rally, and the documentary includes an interview in which she says: “My whole body was trembling, and I had hot sweats. And I was somehow captured, as if by a magnetic force.” They met that year, and later, impressed by the film she directed and starred in, The Blue Light (1932), he asked her to document an upcoming Nazi rally in Nuremberg.

While she made a one-hour film of that rally, a Nazi rally in 1934 was the subject of Triumph of the Will, her first masterpiece. From the beginning she played into the mythology of power, showing a plane soaring through billowing clouds and then landing, Hitler emerging from it like a saviour descended from the heavens. Later, the film cuts between rousing speeches, ecstatic faces and the spectacle of thousands gathered in Albert Speer’s monumental rally grounds.

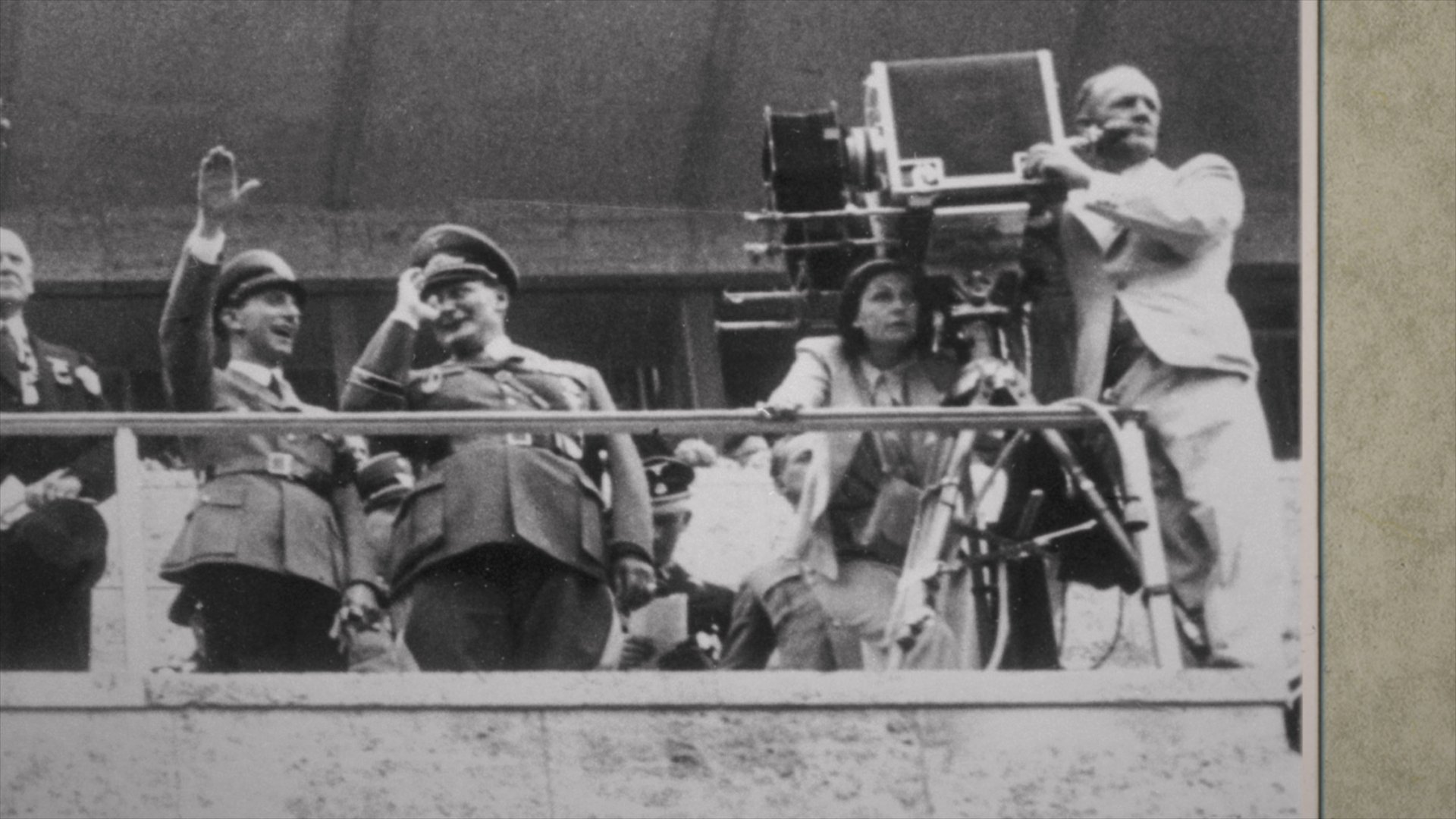

Leni Riefenstahl (right, next to camera) filming Olympia next to Joseph Goebbels (far left) and Hermann Goering (centre) in 1936 © Vincent Productions

While Riefenstahl was never a member of the Nazi party, what has been disputed is how much she supported it and how much she knew about its programmes to eliminate millions of Jews, any political opponents and countless others—and when. The documentary reviews an oft-mentioned incident while she was shooting Tiefland in the early 1940s, when she made use of Romani and Sinti detainees.

“When she stopped filming, they all went back to their camps,” Maischberger says. “Many of them were deported to Auschwitz and they have been killed.” Riefenstahl later insisted that she did not know her extras’ fates, that she knew nothing about politics because she was, she said, first and foremost an artist.

After the war, Riefenstahl felt she was persecuted. Veit Harlan, a director who made the incendiary antisemitic film Jud Süß (1940), claimed that he made such films at the government’s bidding; he had a thriving career in the post-war period. Riefenstahl only completed two films after the war: Tiefland, which was eventually released in 1954, and Impressions Under Water (2002), a documentary of underwater footage.

For both Maischberger and Veiel, Riefenstahl’s story is especially timely given the global resurgence of right-wing populism, as well as the lies she perpetrated. “I want to understand, but I don’t want to exonerate,” Veiel says. “There’s always the difference between understanding and not apologising or excusing her on any level regarding her responsibility, regarding her guilt.”

Watch the trailer for Riefenstahl:

- Riefenstahl is available on select streaming services, opened on 5 September at the Quad Cinema and Lincoln Center in New York, and opens on 12 September at the Laemmle Royal and Laemmle Town Center 5 in Los Angeles