Chris Steele-Perkins, the British-Burmese photographer whose work chronicled the changing face of Britain with clarity and empathy, has died in Japan aged 78.

A long-standing member of Magnum Photos, Steele-Perkins was admitted as a full member in 1983, becoming the first person of colour to be awarded that distinction. Though the photographer was reticent to place his heritage within his artistic identity, his presence marked a subtle turning point for a picture agency that had been overwhelmingly white and European in outlook since its founding in 1947.

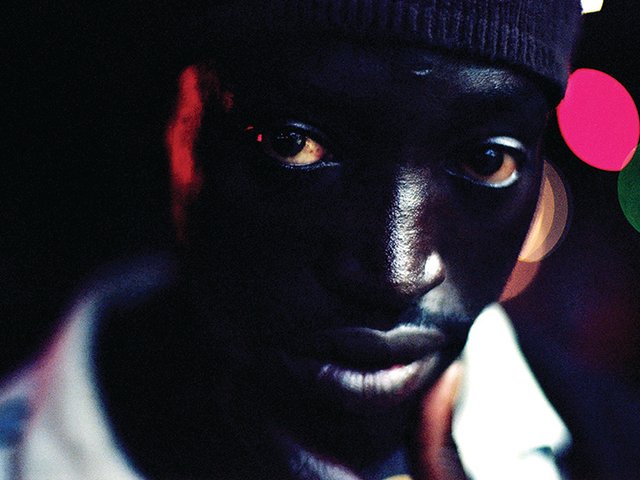

Magnum confirmed the news on Instagram with the message: “It is with great sadness that we announce the passing of the dear Magnum photographer Chris Steele-Perkins.” The agency also shared an image of the photographer, taken at its offices in London in 1994, by his contemporary and friend the late Peter Marlow. A year later, in 1995, Steele-Perkins was voted to serve as president of the famed agency, which he did until 1998.

“I was Chris’s assistant when he was president of Magnum,” wrote the British photographer Tom Craig in response to the news. “An episode that changed my life for the better, Chris was an original and inspirational voice in contemporary photography, with a wide folio of important international work—but some of his British studies were amongst the best of all time.”

Born in Burma (now Myanmar) in 1947 to a Burmese mother and an English father, Steele-Perkins moved to the UK at the age of two. He grew up in County Durham and studied psychology at Newcastle University before discovering photography. By the late 1970s, he had established himself as an acute observer of British life.

His breakthrough came with The Teds (1979), a study of the Teddy Boy subculture that combined dispassionate detail with flashes of humour and warmth. The Teddy Boy aesthetic arose from working-class youths adopting the Edwardian styles of the upper classes as a form of self-assertion; by canonising it, Steele-Perkins demonstrated a visual grasp of Britain’s class system and cultural codes that proved prescient.

What distinguished Steele-Perkins throughout his career was a willingness to go where others did not. In 1970s and 1980s Britain, while many of his contemporaries focused on institutions or political unrest, Steele-Perkins instead turned his camera towards overlooked spaces. Many of his images from this period are distinguished by a sense of motion and dynamism.

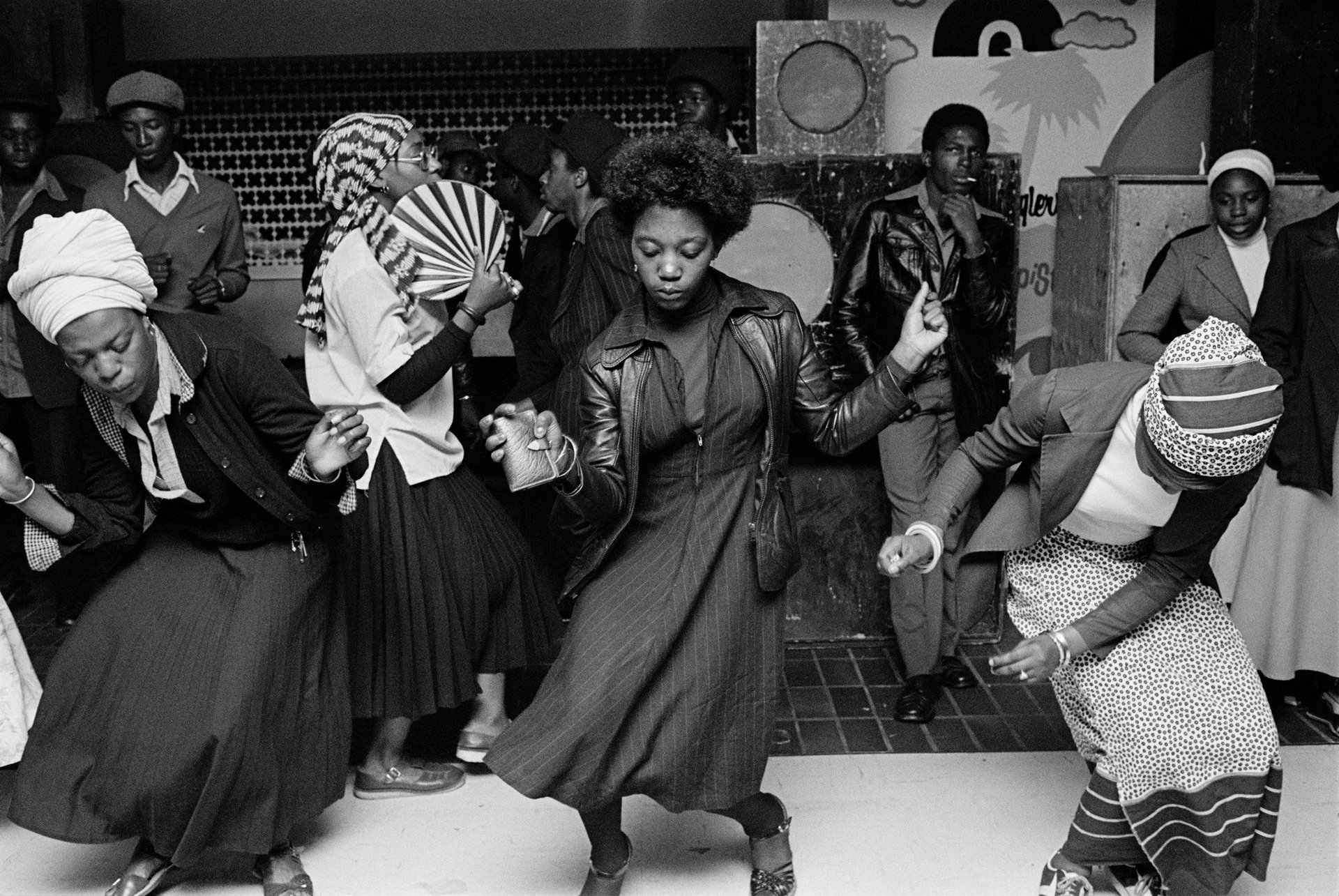

G.B. ENGLAND. Wolverhampton. Disco. 1978

© Chris Steele-Perkins/Magnum Photos

One of his most celebrated photographs, from 1978, shows three Black women dancing in a Wolverhampton dance hall, caught mid-gesture. The image was taken in the years after the local member of parliament, Enoch Powell, gave what became known as the “Rivers of Blood” speech, in which he riled against the anti-discrimination Race Relations Bill. It is an image of style, rhythm, joy and release, taken with curiosity and respect, at a time when Black British communities were rarely represented on their own terms in mainstream or press photography.

Steele-Perkins’s commitment to documenting the breadth of British identity culminated in The Pleasure Principle (1989), a cool-eyed survey of consumerism and aspiration in Thatcherite Britain, and, later, England, My England (2009), a panoramic account of life across the country over three decades. “I wanted to make sense of who we were,” he said of the project, “and to reflect the contradictions of Englishness.”

Steele-Perkins’s career, however, extended well beyond Britain. For Magnum, he reported on famine in Africa during the 1980s and worked extensively in Afghanistan. Another strand of his practice reflected his personal ties.

His second marriage was to the Japanese writer Miyako Yamada, and across several series—Fuji: Images of Contemporary Japan (1997), Tokyo Love Hello (2007) and Northern Exposures (2007)—he explored Japan with an eye both intimate and observational. For a photographer of Burmese descent raised in England, his perspective on Japanese society was at once informed by closeness and distance, making these works among his most nuanced.

Writing on Instagram, Yamada paid tribute to her husband. “His eye has always been kind and sincere…” she wrote. “We would like to extend our sincere thanks to all those who love Chris's photography. His life as a photographer has been exciting, rewarding and enriching.”

Despite this, recognition for his work came late. Steele-Perkins’s photography was widely respected by fellow practitioners, and shows at The Photographer’s Gallery in 2019 and the Irish Museum of Modern Art in 2022 lifted his profile, but his place in the public imagination was less secure than some of his peers.

Critical acclaim, however, was not Steele-Perkins’s focus. In later years, projects such as The New Londoners (2019), which portrayed families from every nationality living in the capital, demonstrated the continuity of his interests: a fascination with how identity is built in everyday life, and how it relates, ultimately, to the relationships we hold most dear.