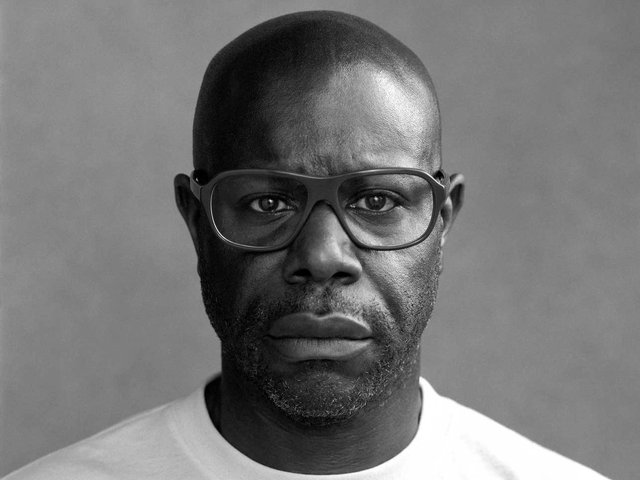

Forty years ago, when he first moved to Amsterdam, the artist and film director Steve McQueen would look at 17th-century cityscapes by Johannes Vermeer in the Rijksmuseum and wonder what lay behind the “random, mundane” actions depicted in them.

Now he has captured the ghosts of a modern city, once occupied by the Nazis, in a 34-hour film being projected onto that same museum. It is the first time his film Occupied City, which explores the stories of more than 2,000 Amsterdam locations during the war years and now, is being shown as the full work of art that he intended to create.

“When you see a painting, you have no idea of the context or who the people are,” he told The Art Newspaper. “This is a mirror image of Amsterdam: it mirrors who we are today.”

McQueen, who won an Oscar for his film 12 Years a Slave (2013) and rose to prominence after winning the Turner Prize in 1999, worked on this project with historian and filmmaker Bianca Stigter. Stigter documented a sobering history in her book Atlas of an Occupied City, Amsterdam 1940-1945. McQueen’s images of the same locations were shot between 2020 and 2023, as the country went into Covid lockdown and witnessed both Black Lives Matter demonstrations and climate change marches.

McQueen explains it was always his intention to show all of the locations that he and Stigter filmed

© Rijksmuseum, Jordi Huisman

Eighty years after liberation, the work is being projected silently onto the south façade of the Rijksmuseum continuously from September 12 to January 25, 2026, while also being shown with sound and voiceover in the auditorium. It tells stories of the Nazi occupation in which three-quarters of the Dutch Jewish population was murdered, alongside Roma, Sinti and other dissenters.

McQueen is loath to tell the viewer what to think but his film reflects on the importance of both freedom and also what lies behind a rich surface. “You are living in a 17th-century city [in Amsterdam],“ he says. “There’s not a lot of evidence of that particular past, [but] I felt that there were two or three narratives going on at the same time: of the 17th century, of the war and the present.”

Stigter adds: “The strange thing about Amsterdam, especially the centre, is the history of the 17th century you can see in the buildings and the beautiful canals, but you can’t see what happened when Anne Frank was hiding. This particular part of history is only visible in the monuments erected afterwards—it is kind of invisible to the eye at first glance.“ The scale of the story Occupied City tells, she continues, “gives you an inkling of the overwhelmingness and the magnitude of what happened during that time”.

While the Dutch focused on stories of resistance and resilience after the war, there has been more attention to collaboration and the suffering of the Jewish population in particular in recent years.

For the original feature release, much of what the McQueen and Stigter recorded had to be cut, to fit the—still lengthy—four hour and 26 minute run-time. McQueen said his intention was always to make an work featuring more than 2,000 addresses, so that the viewer could experience something of the passing of history, the relationship between then and now. “What I want to do with 34 hours was to allow time to pass,” he said. “[Time that] is bigger than all of us.”

- Occupied City, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 12 September-25 January 2026