Olafur Eliasson, the Icelandic Danish artist known for ambitious installations with ecological messages, is working on his first public commission in the Intermountain West that draws inspiration from the Great Salt Lake in Utah. Called A symphony of disappearing sounds for the Great Salt Lake, the temporary installation will debut in the early spring of 2026 in a public park in Salt Lake City and consist of field recordings of the Great Salt Lake’s wildlife and a changing light projection. The largest of its kind in the Western Hemisphere, the Great Salt Lake is experiencing an ecological crisis due to a significant decline in water levels. In 2022, the lake reached its lowest level after decades of diverting water for the growing local infrastructure and due to worsening effects of climate change.

“When I first encountered the Great Salt Lake and was introduced to the complex issues that are affecting the lake, I asked myself what art could contribute to the discussion,” Eliasson tells The Art Newspaper. “The lake is both deeply local—intertwined as it is in the lives of nearby farms and communities—and part of vast, planetary systems of water flows and animal migration. My artistic aim is to bring these scales together, to invite people to experience the lake not only at the human level but also through a broader perspective.”

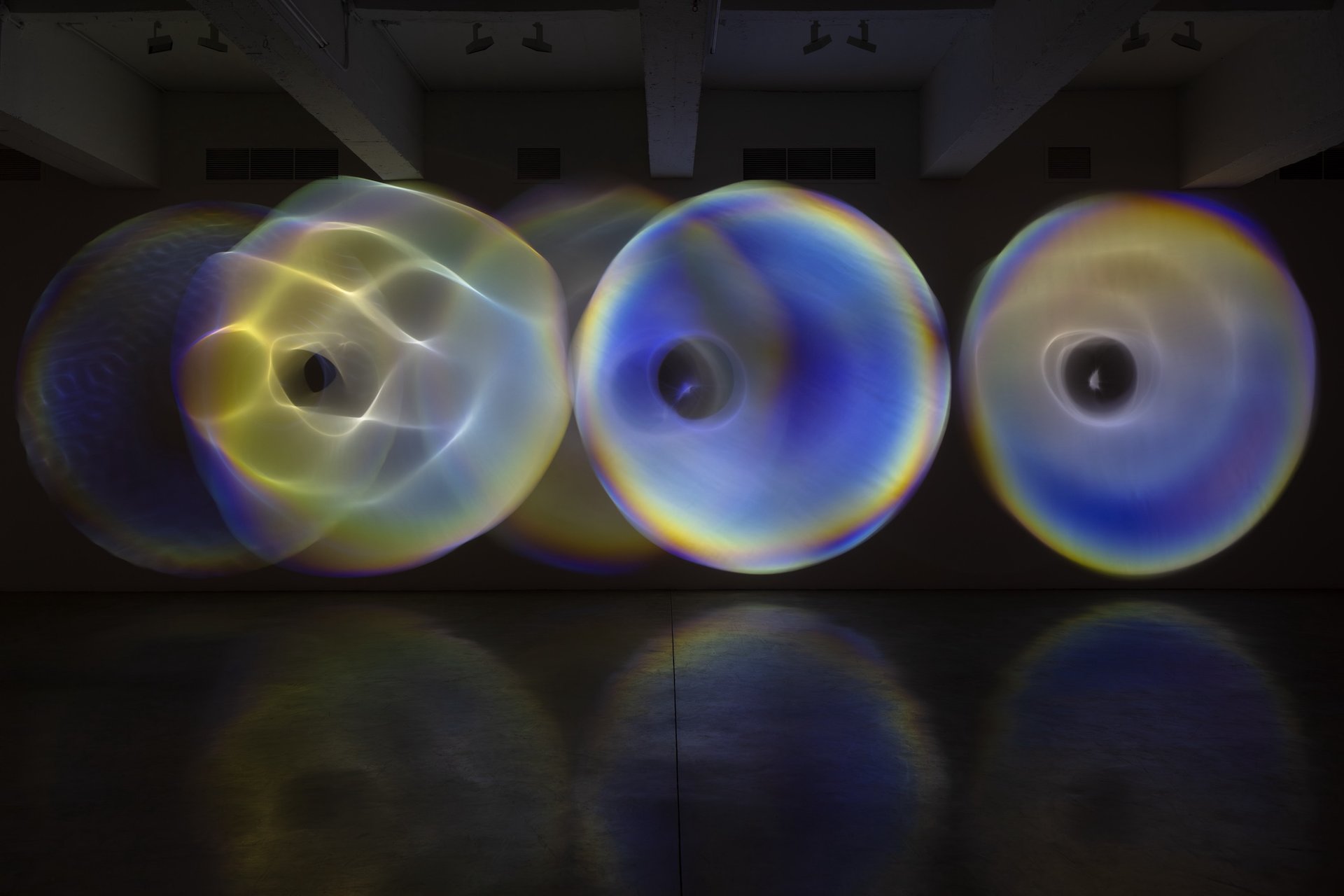

Eliasson intends for the installation to “amplify what is already there”, he says. His piece will feature sounds from the lake including birds, insects and the water itself. The projections will reveal large, illuminated spheres that change depending on the field recordings, giving a visual form to the lake’s frequencies. “These recordings make it possible to listen with the lake, and to become attuned to the more-than-human world,” Eliasson says.

The project is part of Wake the Great Salt Lake, an initiative to commission artists to create temporary public works that raise awareness of the issues facing the lake and inspire action to protect its future. Wake the Great Salt Lake is supported by Salt Lake City Arts Council, Salt Lake City Mayor’s Office and Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Public Art Challenge.

“Olafur Eliasson has a gift for capturing imaginations and inspiring engagement,” Michael R. Bloomberg, the founder of Bloomberg Philanthropies and Bloomberg LP and the former mayor of New York City, tells The Art Newspaper. “For more than a decade, we’ve supported his powerful public art in New York, Paris, London and other cities. Now, his latest work aims to help open our senses to the Great Salt Lake and the crisis it’s facing. And in doing so, he’ll help forge more personal connections to the lake—and the importance of sustaining it.”

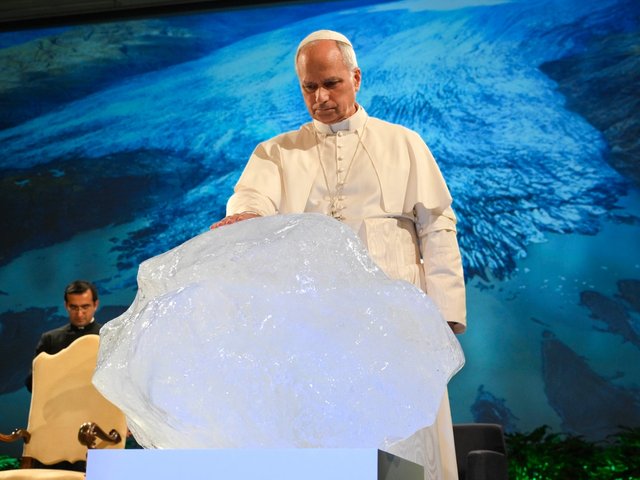

Olafur Eliasson, Your psychoacoustic light ensemble, 2024 Photo: Pierre Le Hors. Courtesy of the artist; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles. © 2024 Olafur Eliasson

Indeed, sustaining the lake is crucial not just for the local flora and fauna, but also for animals like migratory birds. Hundreds of species representing millions of birds feed on other organisms that normally thrive in the Great Salt Lake, such as brine fly larvae and brine shrimp. Some also use the area for nesting and roosting. Without the lake, these species and the ecosystems they support are at risk of potentially irreparable damage.

The mission of Wake the Great Salt Lake is also to underscore the economic importance of the lake. The migratory birds, for example, support local tourism by attracting eager bird watchers. “Environmental issues like the decline of the Great Salt Lake don’t occur in a vacuum—they are deeply connected to global systems and create ripple effects that extend far beyond our region,” says Felicia Baca, the executive director of the Salt Lake City Arts Council. “Caring for the lake means caring for the well-being of communities both near and far. Addressing this crisis requires collaboration among people across government, science, business and the arts.”

While Eliasson leaves his artwork open to multiple interpretations, he hopes his installation can “bring people together around a positive vision, one that amplifies existing local efforts to protect the lake and the wildlife that depend on it, and that affirms that the problems here are solvable despite their complexity”, he says.

He adds: “What matters to me is not that visitors leave with a single message, but that they leave with a renewed sense of connection: to the lake, to the birds and to one another. The work asks us to lean into the tension without passing blame, and to recognise that meaningful change will only come if we move forward together.”