Robert Redford, the Oscar-winning actor, director and founder of the Sundance Institute, has died aged 89 at his home in Sundance, Utah. Redford’s death was announced yesterday by his publicist, who confirmed that he died in his sleep, surrounded by loved ones.

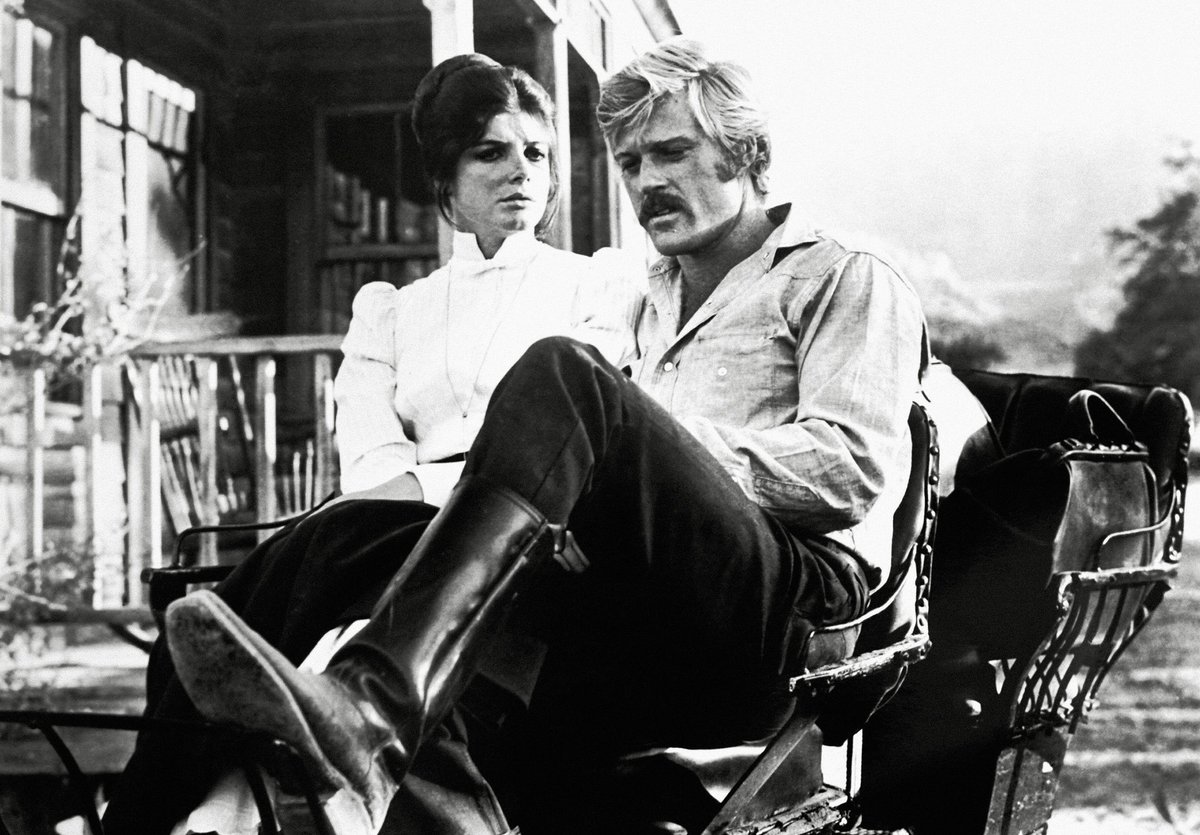

Best known to global audiences for roles in films including Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and All the President’s Men, Redford’s performances and persona embodied America’s self-image in the superpower decades after the Second World War. As a leading man he was principled and rugged, often compromised, always restless for change and sometimes necessarily violent.

But before Hollywood brought him fame, Redford’s first ambition was to be a painter. Later in life, he was a dedicated collector and cultural philanthropist.

An education in the arts

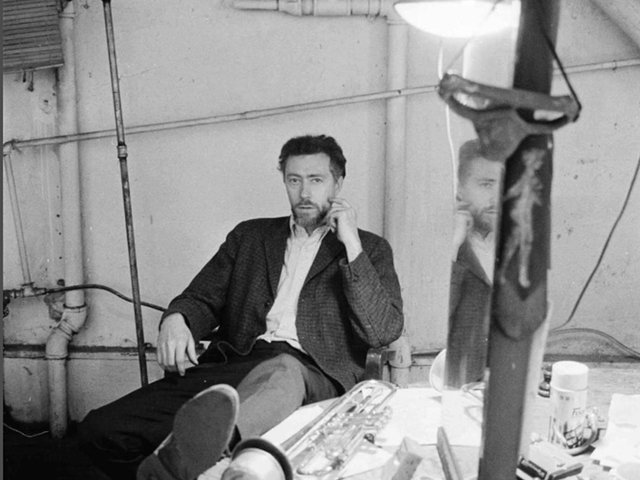

Born in Santa Monica in 1936, Redford studied at the University of Colorado where he pursued painting before shifting to theatre. He later travelled through Europe, spending time in Florence before enrolling at the Académie Julian, a prestigious 19th-century Paris art school that has attracted generations of international students.

Back in the United States, he continued his studies at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where he later described his attempts to refine his draughtsmanship and absorb the techniques of modern American painting. In interviews, he recalled being “very serious” about becoming an artist, before slowly conceding to the pull of acting.

However, his training in art left an imprint. Throughout his career, Redford was known for gestural acting, a form of performance indebted to the history of art. He spoke of trying to capture the expressive movements of paintings he admired, suggesting that his acting style drew as much on visual as theatrical traditions. Later, as a director, he demonstrated an exacting—and perhaps sometimes excessive—eye for composition, light and cinematography.

This belief in filmmaking as a multidisciplinary pursuit underpinned his founding of the Sundance Institute in 1981. Conceived initially to support independent filmmakers, the institute quickly expanded to host cross-disciplinary art programmes, commissioning residencies that paired film-makers with theatre artists or hosting visual art workshops alongside film screenings.

Collecting and directing

Redford’s family life was also close to the arts. His second wife, the German multimedia artist Sibylle Szaggars Redford, whom he married in 2009, has exhibited internationally in Europe, North America and Asia. In 2016, Szaggars was the recipient of the US State Department’s Art in Embassies Program for the US Embassy in Paramaribo, Suriname. Ten of her works have since been permanently displayed in America’s embassy in the South American country.

Redford and Szaggars’ homes in Utah and California reflected their work. Their art collection was extensive and varied, with a particular focus on pieces by Native American artists, as well as noted documentary photography. But this interest did not begin with Szaggars—by 1989, according to Architectural Digest, Redford’s home was already filled with textiles, bronzes and paintings spanning the three major periods in Native American art.

In later years, Redford’s final film projects reflected his aesthetic training. All is Lost (2013), his near wordless performance as a sailor on a lost and sinking boat, was inspired in part by the vastness of the sea in works by J.M.W. Turner and exponents of American Luminism. His final starring role, The Old Man & the Gun (2018), cast him as a gentlemanly bank robber still testing boundaries late in life—a valedictory performance that critics recognised as a farewell both to acting and to a particular vision of American independence.

Though he never entered politics, Redford spoke out consistently on behalf of Native communities, environmental causes and freedom of expression in the arts. While he voiced concern about the rise of populism in American political life, he also acknowledged the desire for cultural renewal, and for art to remain something that could reach working people. His work, both on and off screen, can be seen as an attempt to channel that desire.

As an actor, Redford did not just embody post-war visions of America; he encapsulated his chapter of American history. Yet he was also something else: an artist who never relinquished the struggling painter’s sensibility, even as cinema made him a star.