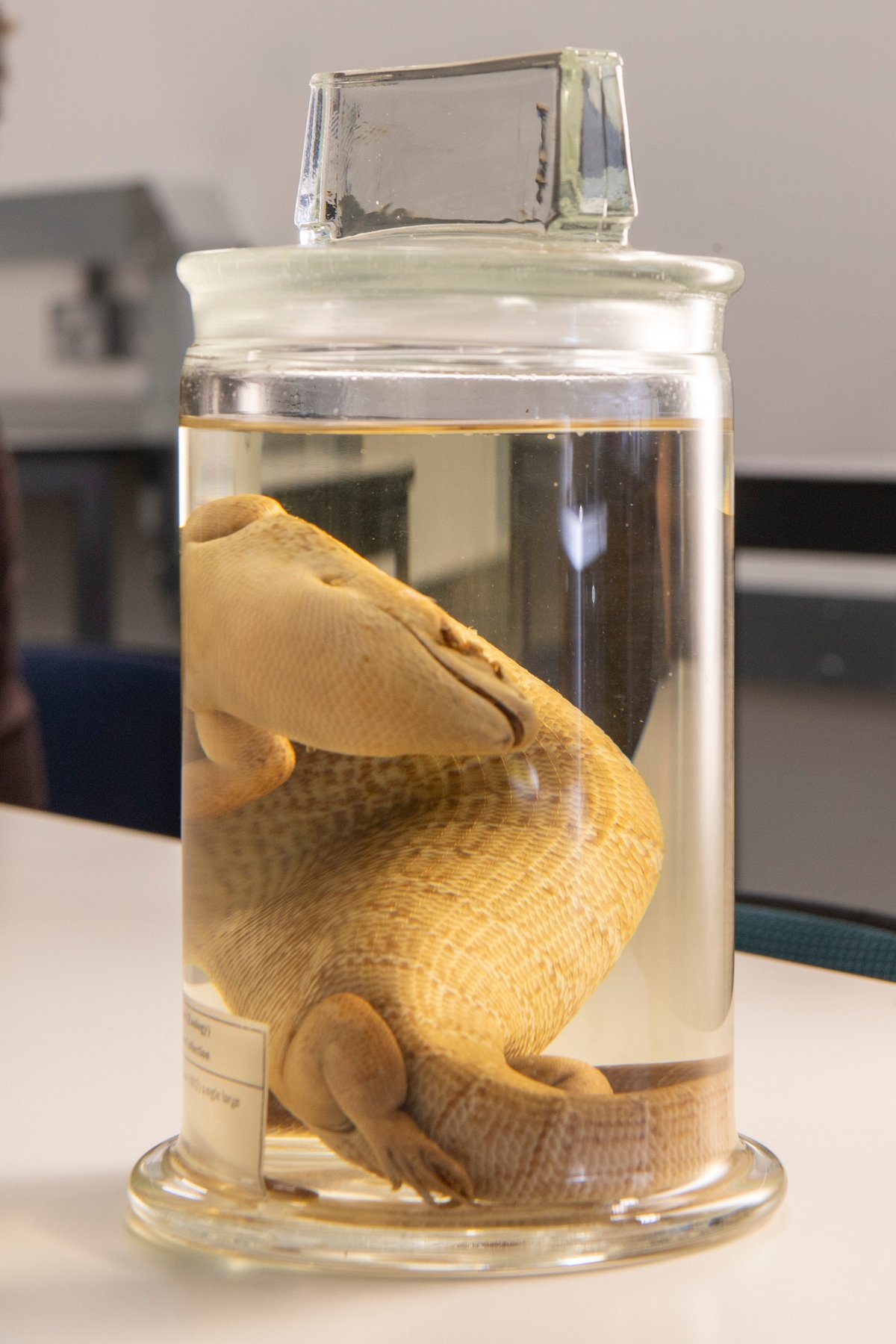

In April 2024, the first repatriation of a natural history specimen to the English-speaking Caribbean occurred between the University of the West Indies in Jamaica and the University of Glasgow in Scotland under a memorandum of understanding. The specimen, an extinct Jamaican giant galliwasp, a reptile which the team named Celeste, was last documented as seen in the 1840s. The specimen is now in the national flora and fauna collection of the Natural History Museum of Jamaica.

Repatriation responds to European colonialism and expansion. In the Caribbean, colonisation resulted in the systematic depopulating of Indigenous peoples, the forced importation of Africans, and the arrival of Indians and Chinese under indentureship schemes.

Imperial expansion also relied on cultural extraction and theft. In Jamaica, cultural items were taken during Spanish (1492-1655) and British rule (1655-1962) and classified as patrimony of empire. Their removal in the name of empire represents looting, and their repatriation establishes a restitutive process to reclaim material cultural identity.

Repairing the damage

The repatriation of cultural items, including art, is an extremely complex one shaped by legal, national and international policies. Repatriation functions as part of a larger restitutive process that seeks to repair damage due to global histories of looting and the destruction of cultural property.

Unesco’s 1954 Hague Convention was the first international attempt to protect cultural property during wartime. The 1970 and 1995 UniDroit conventions on illicit trafficking of cultural property seek to encourage countries to develop the infrastructure to document and protect cultural heritage from illicit appropriation. While this is only a sample of the conventions protecting of cultural property, they do not address illicit trafficking prior to 1970.

The Intergovernmental Committee on Restitution and Repatriation is an important forum for countries to formally request the repatriation of cultural items, especially those looted during colonialism, but national legislative frameworks like the British Museum Act of 1963 often undermine the repatriation process.

Beat the blockers

Universities can provide an important avenue for repatriation in cases where national policies and laws undermine international conventions and bilateral agreements. The return of Jamaica’s extinct galliwasp gives stakeholders access to a wet specimen for study and has stimulated research on repatriation and colonial collecting within reparative justice debates in the Caribbean.

The reclamation of identity and heritage as restitution has guided many repatriation processes including Jewish cultural material looted by Nazis, the Benin Bronzes, and the return of human remains to Namibia from Germany, and of ceremonial military pieces to Sri Lanka from the Netherlands.

Reclamation of identity is the basis of the Jamaican government’s continued requests for the return of the Carpenter’s Mountain Zemi collection pilfered by Isaac Alves Rebello in 1792 and acquired by the British Museum between 1799 and 1803. The three carvings are the best and largest examples of pre-Columbian Indigenous art from Jamaica. Resistance to returning the collection denies the average Jamaican access to the diversity of Caribbean art dating as far back as the Taíno, Jamaica’s Indigenous population—cultural property collections housed in North America and Europe require visas to visit.

Redefining cultural property

Celeste’s return offers Caribbean practitioners an opportunity to rethink definitions of cultural property. If we define Caribbean cultural material as any physical manipulation, such as painting or shaping, of any material (clay, metal, textiles, wood, etc) for societal use dating from early evidence of human occupation to the present and originating specifically from the archipelagic and coastal areas bounded by the Caribbean Sea, then we exclude flora and fauna. Using a more expansive definition of cultural material to include nature, we must acknowledge that our collections could be anywhere.

Repatriation is a necessary ethical practice that dismantles historical inequity in both access to material culture and construction of cultural knowledge and identity. It is an essential part of restorative and reparatory justice.

- Shani Roper is the curator of the University of the West Indies Museum and a member of the five-person team that returned Celeste to Jamaica from the University of Glasgow, Scotland in April 2024