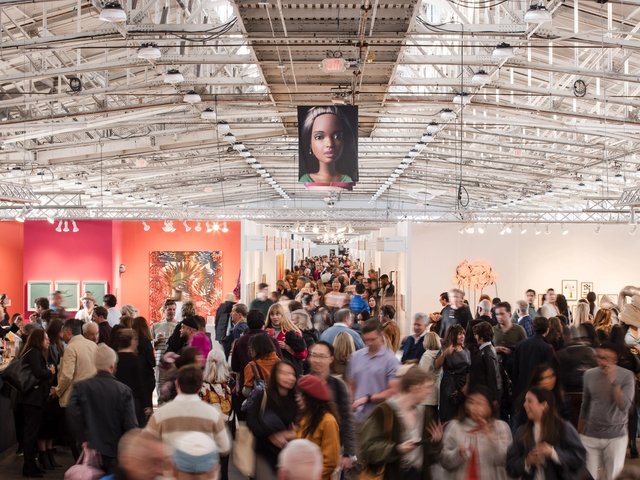

The Atlanta Art Fair (AAF), produced by the events firm AMP (a division of a21), returned for its second edition last week as a bright spot not just on the Atlanta art calendar but in the regional landscape. The fair (25-28 September) illuminated Atlanta’s strengths as a cultural centre. Amid the upbeat crowd, pricey cocktails and the expected mixture of commercial and experimental art, truths emerged regarding Atlanta’s unique identity: its resourcefulness; the strength of its robust, interwoven, creative community; an aggressive, unwavering propensity for friendliness and, perhaps surprisingly for a time when the arts are facing devaluation, a trend toward optimism.

The fair returned to Pullman Yards in the city’s residential Kirkwood neighbourhood. The venue, a historic former railway depot, has faced criticism from local groups for its lack of attention to crowd control, parking and noise.

Despite its fraught reputation, Pullman Yards is an excellent space for an art fair. Perhaps aware of the community concerns, the venue recently launched an artist-in-residence programme, which was highlighted and promoted at the fair. The large industrial space hosted 75 local, national and international galleries and arts organisations, as well as a stage for AAF’s popular theatre programming.

The fair’s organisers and exhibitors seemed better acclimated to the space on their second outing. Last year, many participants and attendees were experiencing their first-ever art fair. The energy was more nervous, and the anxious question leading up the opening was some version of: “Is this going to be legitimate?” This time, participants knew what to expect, trusted AMP more and knew how to use the stands to their advantage.

A panel during the 2025 edition of the Atlanta Art Fair Photo by Walker Bankson. Courtesy of AMP, a division of a21.

Around 3,500 people attended the VIP preview and opening night on 25 September, according to the organisers. Many of them seemed to have received their VIP tickets for free via a widely circulated link. Several exhibitors said they only learned they were going to participate in the fair a few weeks beforehand and were given a discounted rate on their stands. If the organisers were concerned about participation and attendance, the adjustments they made seemed to work—the fair was robustly attended every day.

Adamantly Atlanta

Several factors differentiate this fair from the norm and mark it as distinctly Atlantan. For one, chatting with strangers is non-negotiable. The secret weapon of the Atlanta art scene might be friendliness. It is said that to become part of the Atlanta art crowd, all you have to do is show up, then you’re in.

“They want to talk to you. They want to engage. It’s not the same when you go to the fairs [in New York or Los Angeles]. People walk by, you won't get spoken to. It’s just a different energy. But here you have to talk, you have to smile, you have to greet,” says Lauren Jackson Harris, last year’s guest curator of the fair and the co-founder of Black Women in Visual Arts , an exhibitor this year. “We want to have that familial feel.”

Ato Ribeiro, an artist who showed his work at the fair as part of Atlanta Contemporary’s studio art programme, described the second edition as more in line with the city’s ethos.

“The identity of Atlanta is seeping more into it,” Ribeiro says. “I’m starting to see how we’re able to take an art fair, still make it hit all the marks, but bring that domestic slow-down feel to it where it’s like we can saunter through. It’s the Southern pacing.”

Marc Horowitz, an artist based in Los Angeles who showed charmingly skinny, thickly painted portrait “slices” in the narrowest booth at the fair (which he specifically requested to best compliment the work), put it another way.

“I keep describing it as being post-cringe,” says Horowitz. “Nobody really cares here, and everybody gets along. I’m telling you, it’s somewhat utopic. It’s way less pretentious.”

The sentiment was intended as a compliment, but the art community in Atlanta cares a great deal and not everyone gets along. There is a great deal of pretension if you look for it, and the city’s funding structures make it far from an artists’ utopia. But there is something to Horowitz’s idea of post-cringe and this impression that everyone got along, while no one cares much about being cool. It might be hard for visitors from Los Angeles or New York to understand the experience of being an artist or art worker in the American South, where the scarcity of resources and lack of government support is so extreme that the community seems to have bypassed competitiveness and gone straight to emphasising resource-sharing and mutual aid, or at least trying to. There is, in absolute seriousness, no other way to survive.

Appropriately then, a hallmark of AAF is its affordability, especially compared to major fairs like Art Basel Miami Beach or The Armory Show. This allows regional galleries to showcase their artists to national and international audiences. The Nashville-based gallery Tinney Contemporary travelled to Atlanta for its first fair in part because of the proximity and the cost-effectiveness.

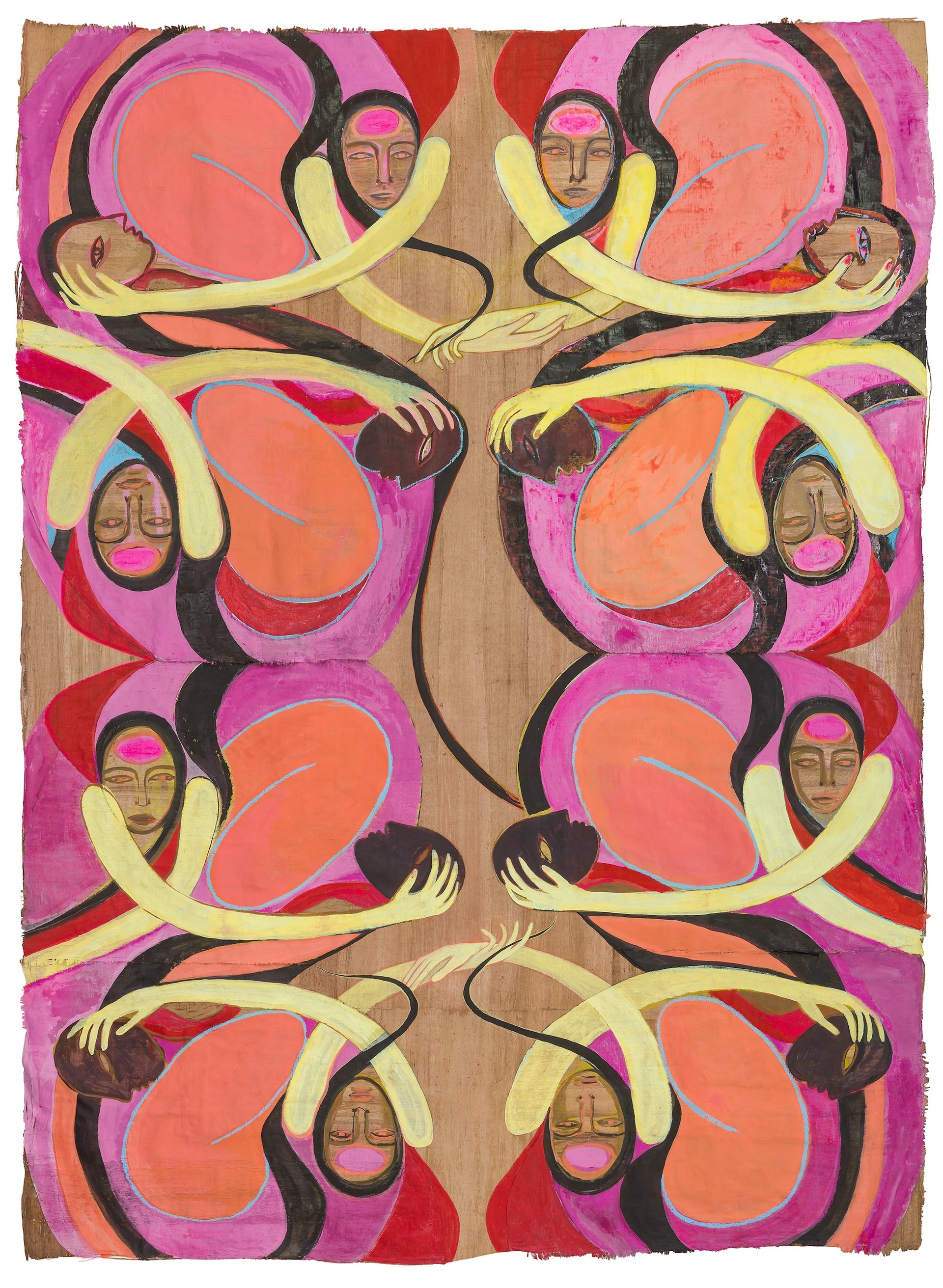

Kimia Kline, Leave Light On, 2025 Courtesy of the artist and Tinnery Contemporary

“We love the fact that it was a smaller fair to begin with, and that it was regional. We felt like there was more reason to invest in the opportunity to participate in a fair that felt more communal,” says Joshua Edward Bennett, Tinney Contemporary’s director. “The fact that there’s local buy-in made us feel more confident in that decision. To be quite frank, the cost to get in was also very appealing. A lot of the bigger fairs seem a little bit more prohibitive for a gallery of our scale and of our price points.”

The gallery showed a compelling selection on its stand, including Leave Light On (2025), a large ink-and-pastel piece by Kimia Kline in which a kaleidoscope of pink, yellow and orange bodies, arms and hair wrapped around each other. Bennett says he was pleased with the sales and described the gallery’s AAF experience as a “great success”.

Another standout at the fair was Third Ear, Second Skin, an exhibition of sculptures organised by Melissa Messina, this year’s guest curator, featuring works by Krista Clark, Sonya Yong James and Vadis Turner. Clark’s work, with its mix of heavy concrete elements and delicate wooden rods, acted as a commentary on labour and construction, particularly unfinished or in-progress construction.

Sculptures by Krista Clark in Third Ear, Second Skin, an exhibition at the 2025 Atlanta Art Fair curated by Melissa Messina Photo by Walker Bankson. Courtesy of AMP, a division of a21.

The small-but-mighty Black Women in Visual Arts stand, curated by Harris, showed works by three Southern-based Black women artists: Candace Caston, Victoria Dugger and Ariel Dannielle. Caston, who also had work on Tennessee Gallery’s stand, is an emerging artist with an eye for slick collage. Her works play with perspective and shape, giving form to a kind of surrealism. Dugger, whose star is quickly rising, combines bright textile works employing beads, fur, and embroidery with elements of collage to create subtly subversive scenes of American life.

Standout threads

Strong textile work was a prominent feature of AAF this year. Notable examples included Zipporah Thompson’s frenetic, deconstructed tapestries, which use fraying netting and loosely connected fabrics to meld references to a splintered natural and spiritual world (and were shown by the Atlanta-based Whitespace Gallery). Qualeasha Wood, who combines elements of internet and social media culture with Black Femme iconography and traditional craft-making, presented EBONY.ONLINE (2022) in the impressive stand of TFA Advisory, which is based in North Carolina (and also showed ceramic works by Atlanta favourite Jiha Moon). Jonathan Carver Moore Gallery from San Francisco showcased Adana Tillman, who uses heavy quilting and unconventional patterns to depict moments of Black domestic life, such as two women playing cards outdoors amid a dreamy garden scene.

Zipporah Camille Thompson, Déjà vu, 2025 Courtesy of the artist and Whitespace Gallery

The fair was not the only major event happening in Atlanta last week. The Art Writing and Publishing Symposium, presented by Art Papers, took place at Ponce City Market, drawing many writers and critics to the city as well as some fair participants. According to Paul Salsieder, the manager at the Portrait Society Gallery in Milwaukee, one of the deciding factors for participating in the AAF was the draw of the symposium. Additionally, Site, an ambitious one-night-only art event held at the historical Goat Farm in West Midtown, drew huge crowds for its second year, with many fair participants coming to see the many installations and pop-up exhibitions.

Between the welcoming atmosphere, strong regional participation and tighter organisation, the AAF seems to have gotten its sea legs and demonstrated Atlanta’s key strengths in both its culture and geographical location. In general, attendees and participants seemed upbeat. Exhibitors reported that sales went well enough, and the organisers said attendance was up by 1,500 people compared to last year, with a total of 13,500 visitors over the fair’s four days.

Of course, the financial realities of the arts in the South still loom and it remains to be seen whether the fair will renew its contract and return in 2026. In the arts in general, and especially in the South, the success of an event does not guarantee its continuation if the money is not flowing. But Atlanta is resilient, and the systemic devaluation of the arts and funding cuts are nothing new. Regardless of whether or not AAF returns, the art scene in Atlanta is not going anywhere.