Emily Kam Kngwarray’s rise to fame in the late 1980s and early 90s in her native Australia was swift and meteoric—but with it came enormous demand from dealers and others, some of whom took advantage of the artist and members of her community, according to the two curators behind Kngwarray’s major solo exhibition currently at Tate Modern in London. The show was first presented at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Canberra two years ago.

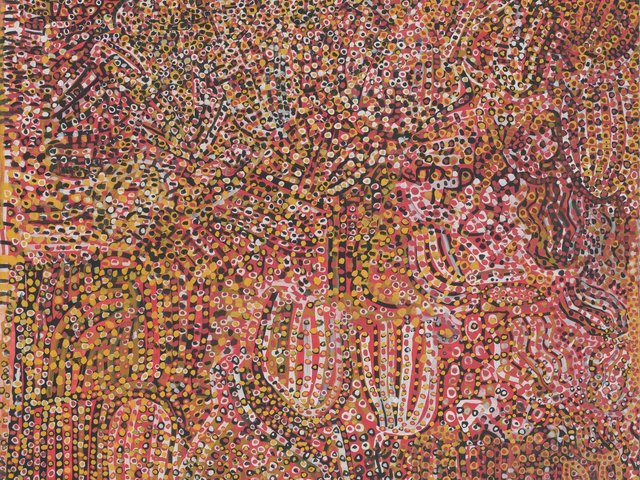

Born in 1914 in Alhalker Country, home to the Anmatyerr people and located in the Northern Territory of Australia, Kngwarray was a ceremonial artist, storyteller, cultural custodian and matriarch who spent much of her adult life working on cattle stations built by white settlers who renamed the surrounding area Utopia. It was only in her mid-70s that she first put paint to canvas, but Kngwarray was propelled to art world stardom almost overnight after her first painting, Emu Woman (1988-89), was shown in Sydney in 1989, drawing critical acclaim and beginning an extraordinarily productive seven years in which it is estimated she painted around 2,000 works of trusted provenance.

Almost 30 years after her death, Kngwarray’s Earth Creation I (1994), which sold for AUS$2.1m in 2017, still holds the record for the highest price paid for an Indigenous artist, as well as for any Australian female artist. The work, which is owned by Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest, a mining magnate with significant investments in cattle ranches across Australia, has not been included in the Tate show.

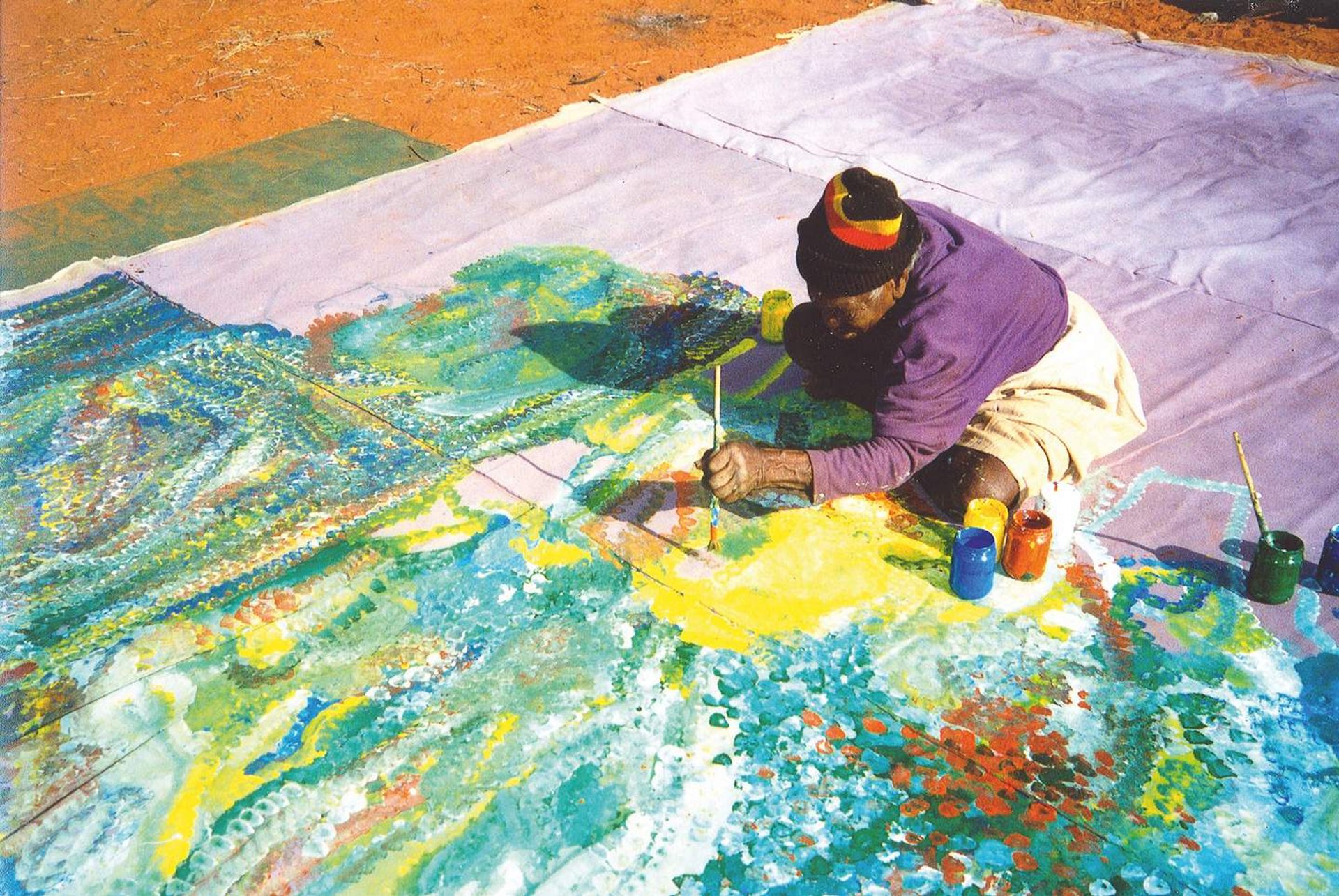

Emily Kam Kngwarray painting Earth's Creation I in the Utopia region, Central Australia, 1994

Courtesy of Tate

In the final years of her life, Kngwarray’s main dealer was Don Holt, the owner of Delmore Downs, a cattle station next to Utopia where Kngwarray worked. Writing in the Tate show’s exhibition catalogue, the curators Kelli Cole and Hetti Perkins note how, in the late 1980s, the market for Aboriginal art began to take off in part due to the 1988 Australian Bicentenary. “Northern Territory station owners diversified their pastoral interests to take advantage of the creative talent of local artists, including Kngwarray, and other individuals who had previously worked for government arts agencies established their own dealerships,” they write. “Independent entrepreneurs of diverse backgrounds entered the fray, fostering an opaque system of accountability that took advantage of the inexperience of artists and the poor socio-economic status of their communities.”

Cole, a Warumungu and Luritja woman, tells The Art Newspaper that the relationship between artists and the figures who champion them “highlights the complex histories and power dynamics that exist in Australia”. She adds: “Even in the art world, an individual who has benefited from the historical system of land dispossession can also become a key figure in the commercialisation of Kngwarray’s work, which is so deeply connected to that same Country.”

The curator notes how she and Perkins, an Arrernte and Kalkadoon woman, made several key choices about which works to include in both the NGA and the Tate shows, crucially not including some of the last paintings Kngwarray made before she died. Cole points to the context in which those works were made. “Because Kngwarray was already an elderly woman, who was growing increasingly frail, and near the end of her life, we chose to focus on works leading up to—and made—during the height of her career,” she says.

Some of Kngwarray’s relationships with dealers were sympathetic. As Cole points out, the artist was a strong-minded woman who had agency in many of her dealings. The first to have longstanding relationships with Kngwarray were the linguist Jennifer Green and Julia Murray, who established the Utopia Women’s Batik Group workshops in the late 1970s as part of government efforts to bring skills to women in the community.

Transitioning from batik to painting

“Perhaps unbeknownst to them at the time, Jennifer Green, Julia Murray, Deborah Speedy and other community arts workers laid the groundwork for the success of Kngwarray’s career,” Cole says. “Who knows what would have happened if they didn’t assist the women with selling their batiks, or generate revenue, from small supplementary grants, to purchase art supplies? To my mind, they effectively funded the art programme from within, which maintained the momentum, and subsequently the space for Kngwarray and other women from the region to transition from batik to painting.”

It was Rodney Gooch who first introduced canvases to the community. Gooch had been employed by the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association, which had taken over management of the Utopia Women’s Batik Group. One of Gooch’s first projects was to commission a group of paintings titled A Summer Project—that body of 81 works (including Kngwarray’s debut Emu Woman) was acquired by the Australian businesswoman Janet Holmes à Court.

Dealers were flying in on chartered flights to buy Kngwarray’s paintings. Did many of these people have real relationships with Kngwarray? Or was it wholly transactional?Kelli Cole, curator

Cole says Gooch—who married her uncle Robbie Cole—had some understanding of Aboriginal communities and the role art-making played in them as a communal endeavour. According to Cole, Kngwarray would sometimes go to Robbie Cole and Gooch’s house in Alice Springs to paint. “She and other women would paint under a tree or on his veranda, Rodney provided them with biscuits and tea, which they loved,” Cole says. “I suspect the general solitude of being away from the rowdiness of community life sparked different moments of creativity for Kngwarray.”

Early on, Gooch established an agreement to sell some of the community’s art via Christopher Hodges, an artist-turned-art dealer with a gallery in Sydney who renamed his business Utopia Art Sydney after recognising the talent of Kngwarray and others. Cole says Gooch was “very conscious of making sure that he wasn’t exploiting Kngwarray”, only taking a 30% cut on sales, though she acknowledges it was still a profitable business. “Some people will say that Rodney was equally as bad as others, because he made a fortune too,” she adds.

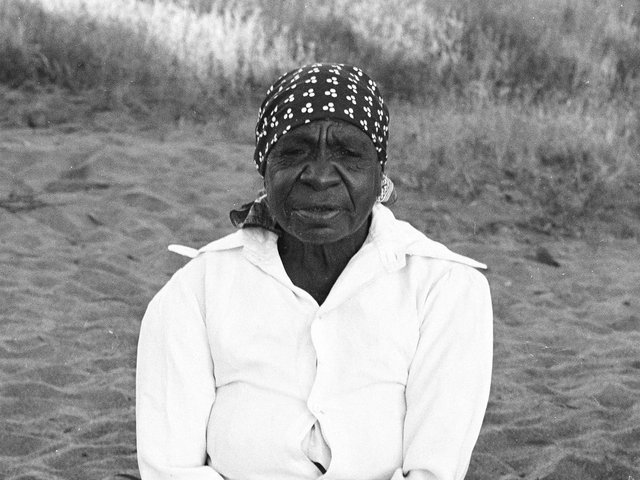

Emily Kam Kngwarray (1914–96), pictured in 1980

© Toly Sawenko

As Kngwarray’s reputation grew, and the Aboriginal art industry flourished, a rush of other market players entered the scene. “Dealers were flying in on chartered flights to buy Kngwarray’s paintings as they were selling for good prices,” Cole says. “But the question is: did many of these people have real relationships with Kngwarray? Or was it wholly transactional?” The curator believes the artist was most content when she was with her community, “painting collectively, as a group activity”.

The Australian secondary market dealer D’Lan Davidson, who recently co-organised a show of Kngwarray’s work with Pace gallery in London (which closed on 8 August), agrees that “there were a lot of people who preyed upon her success”. He notes that there are “two recognised lines of provenance” that his gallery adheres to when it comes to selling Kngwarray’s work: Holt’s Delmore Gallery and Rodney Gooch. Davidson agreed with Pace that they would pay 10% of sales proceeds from their show to Kngwarray’s community (paintings were priced up to $1.5m).

It is a matter of quality and ethics, Davidson says: “It’s been recognised that through those two lines of provenance, the artist was looked after the most. The quality of the work is generally really high, and you know that the artist was being properly recompensed during her life.”

- Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern, London, until 11 January 2026