Two years on from the 7 October 2023 attack by Hamas in Israel and the Israeli military offensive that followed, scores of Palestinian cultural figures have been killed and much of the territory’s cultural and historic heritage has been destroyed. But scattered across Gaza and beyond, many artists remain committed to sustaining their practice as an expression of memory and resilience. The Art Newspaper spoke to several artists and cultural figures living abroad about their experiences, the work they continue to make and their efforts to sustain Gaza’s artistic life.

Dena Mattar, an established Palestinian artist and co-founder of the Eltiqa Group for Contemporary Art, had to cancel a scheduled online interview with The Art Newspaper. Days earlier, her uncle had been shot by Israeli forces outside of a hospital in Deir Al Balah and later died of his wounds. With her uncle’s wife outside Gaza and unable to return, his four children remain alone, a situation that has deeply affected Mattar.

Her distress worsened after she saw images of her mother and other relatives looking frail and emaciated, says her husband and fellow Eltiqa co-founder, Mohammad Al-Hawajri. “Dena keeps on crying,” he says. “Unfortunately, this is our life, this is Palestinian life.”

The couple and their four children left Gaza in April 2024 after six months of displacement, the destruction of their home and close brushes with death that included being trapped under rubble after an Israeli bombardment that killed several of their relatives. The couple now lives in Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates.

Rebuilding their lives has not been easy. “It’s a very heavy time,” Al-Hawajri says, noting that some of his relatives back in Gaza tell him they wish for death to escape their situation.

Mattar and Al-Hawajri continue to make art, though they often question the point of it now. Participating in art events, including Abu Dhabi Art (19-23 November) and the Sharjah Biennial (6 February-15 June), has provided some relief and they are looking forward to taking their children to their group show in Italy this month, which will feature works created mostly in Gaza. “We continue for our children; we left so that they could have a future,” Al-Hawajri says.

While their styles differ, Mattar and Al-Hawajri both use bold, bright colours in their works to show a side of Gaza that is not defined by war. “This has been our job for 20 years. We try to keep hope in our art with our colours,” Al-Hawajrisays. “I hope this war ends soon. I hope I can go back to Gaza. I miss my life there, my studio, my home, my family and friends.”

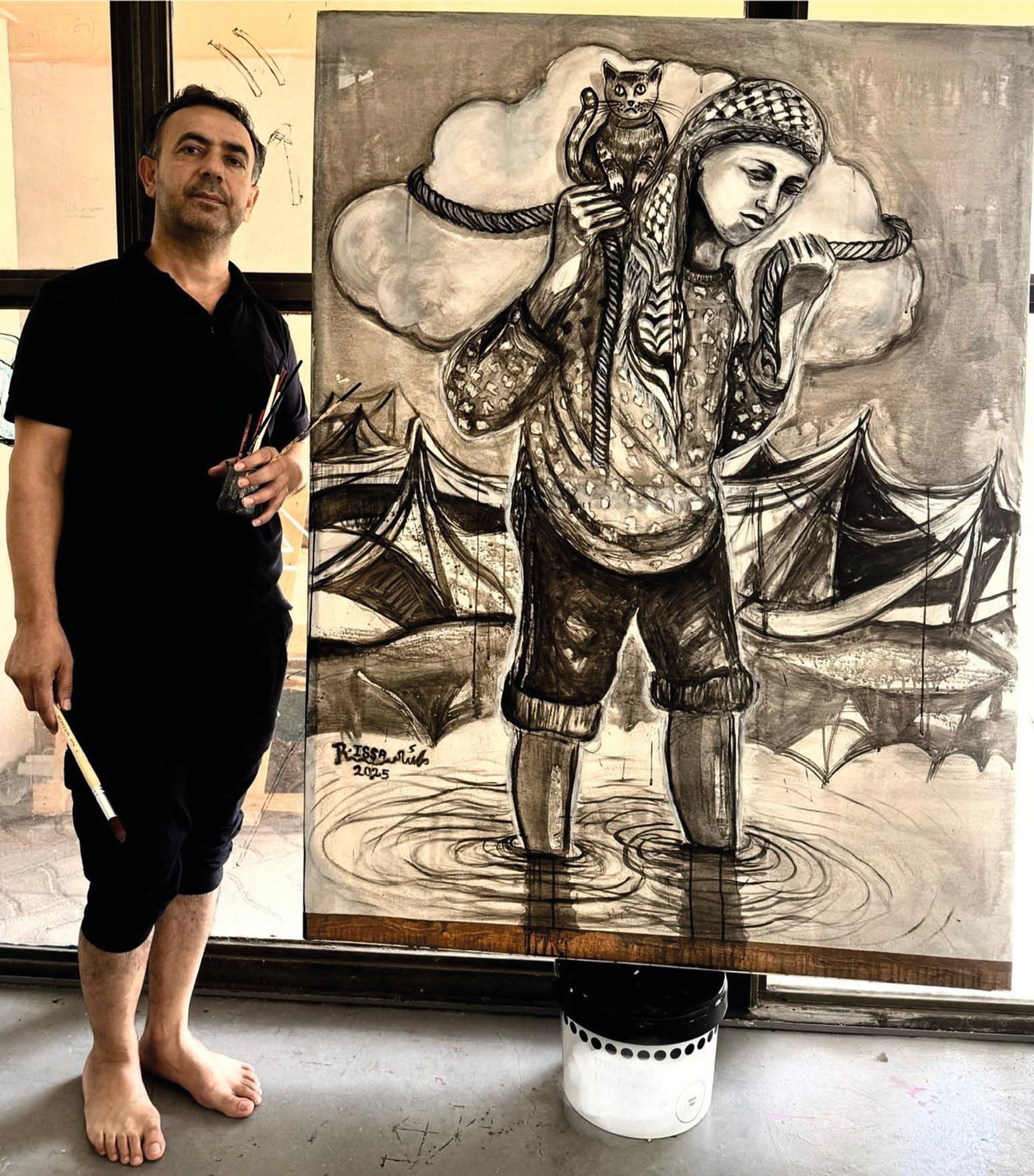

An art scholarship enabled Raed Issa to move to Marseille in France Courtesy Raed Issa

‘We are outside of the hell’

The couple’s close friend and Eltiqa co-founder, Raed Issa, left Gaza in April 2025 thanks to a French art scholarship that secured his exit with the help of the French embassy. “We are outside of the hell,” Issa tells The Art Newspaper from France. In 2024, he tried to leave for Egypt, but while his wife and children were granted visas, he was denied. He convinced his family to leave to without him, promising to follow, but, soon after, Israeli forces closed the Philadelphi Corridor on Gaza’s border with Egypt, leaving him trapped.

After over a year of displacement, living in a tent and fearing for his life, Issa arrived in Marseille, France. “I still can’t believe I am outside of Gaza. I have a chance, thank God,” he says.

Issa left Gaza with nothing but his clothes—not even his phone. “I bring my mind. I don’t forget anything—camps, friends, family, streets, markets. I keep everything in my mind,” he says, adding that he has been writing down all of his experiences.

In France, Issa has finally been able to sleep, something that was impossible in Gaza. “But I feel more tired than when I was in Gaza,” he says, noting that the trauma has caught up with him.

After two months, his wife and children joined him in France. He was stunned by how much they had grown. “I sent a small child to Egypt, and I see a young man now,” Issa says of his 15-year-old son.

A work by Salman Nawati, now based in Sweden Courtesy Salman Nawati

Salman Nawati, the co-founder of the Sahab Museum, a virtual museum supporting Palestinian artists, left Gaza for Sweden in 2022. A part of the Sahab Museum’s new France-funded project was dedicated to supporting artists within Gaza. Developed by the Hawaf Collective, which Nawati also co-founded, an emergency open call drew 200 applications; 39 were selected. Most received grants of €1,000, money desperately needed, though Nawati points out the sum would last only a week in Gaza given the soaring prices.

Artists such as Ahmad Muhanna and Mohammed Alhaj shared their Sahab-funded works on social media. “It was about how we can encourage these artists to create and keep their artistic lives,” Nawati says. The Sahab Museum was conceived in 2020, born from the sense of isolation that Nawati and others felt inside Gaza. “We desperately tried to present our art and culture to the world, to show the side of Gaza outsiders never see. But the world did not give us attention. We felt isolated and it was unfair. So we decided to start our own museum.”

In Sweden, Nawati works as an arts teacher, co-founded the Dahleez Collective, participates in podcasts and audio art, and continues his own projects while looking after his small family. “I’m waiting for a moment to stop, but I can’t stand by and do nothing,” he says. “My children see us and will know we did not sit back during a genocide.”

One of Nawati’s recent collaborations is with the A.M. Qattan Foundation, a British-registered cultural charity, where he co-founded Hassala Art, an urgent appeal aiming to raise $80,000 per month to support around 300 artists in Gaza. “It’s a lot of money, but we can never give up,” Nawati says.

From his new base in Sweden, Salman Nawati is involved in a number of initiatives to support artists in Gaza Johan Ylitalo

Push to preserve

Nawati also sits on the board of ArtZone Palestine, an online platform launched in November 2024 that collects digital images of works by Gaza-based artists. Mahmoud abu Hashhash, ArtZone’s co-founder and the director of the culture and arts programme at A.M. Qattan Foundation in the West Bank, says the idea of a Palestinian digital archive came before 7 October.

“The space given to Palestinian artists, especially emerging artists, had been diminishing over the past five years,” he explains. But the war forced him to bring the launch forward and focus solely on Gaza. “We started hearing about artists losing their works. Some even burned their art [for firewood],” he adds, prompting them to act to record whatever could be saved.

Contacting artists amid war was delicate. He began by sending personal letters to close friends, then others reached out to him. To date, the platform has gathered 1,200 images from around 55 artists, creating a profile for each. “We also tried to capture this disappearing culture and landscape in their biographies,” he says. The process is challenging; many lack good images of their work, the internet is unreliable and some artists are not in the mental space to take part.

Looking ahead, abu Hashhash says the focus will remain on Gaza, given the scale of destruction. He hopes to find partners to help print and sell works, providing financial support for the artists. “Gaza is the most expensive place on earth right now,” he says. “They need help.”