Many people have felt, with a sense of guilty unreality, that the genocide in Gaza is something happening on their phones. This is literally the case in Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk, director Sepideh Farsi’s profile of the young Palestinian photographer Fatima Hassouna, who appears primarily via WhatsApp video calls with Farsi, as well as in photos, text messages, attachments and voice memos. Farsi simply films her phone—she’s visible in the picture-in-picture—and in the movie theatre, at least, Hassouna fills the screen and commands your undivided attention.

Hassouna has a magnetic presence, with straight white teeth often bared in an anxious smile, even as our perception of her is occluded by the raspy audio and laggy pixels that represent the obstacles between the West and Gaza: a physical blockade, degrading communications infrastructure, selective media narratives. Hassouna calls from home, a friend’s house, a shelter, a rooftop—wherever she can get a charge and a signal. The dialogue proceeds in fits and starts, interrupted by sound that glitches, video that cuts out, calls that drop, devices that sometimes rattle with the sudden percussion of Israeli bombs. Hassouna and Farsi, an Iranian-born French filmmaker, speak together in English. The film spans a year almost exactly to the day, from April 2024 to April 2025, and reminds the viewer of the timeline of the current conflict’s first year: the false hope of a ceasefire, the blocked aid, the destroyed hospitals, the assault on Rafah, the rising spectre of starvation.

Farsi jumps right into the deep end during what appears to be their first conversation, following an introduction brokered by one of the director’s contacts—she immediately asks Hassouna if her house has been destroyed. They build rapport as Hassouna moves through moods of alternating defiance (the genocide makes her “proud” to be Palestinian, because “they can’t defeat us”) and depression (it’s sad when you know you can’t have any of your dreams, she begins to say just before the image on Farsi’s phone turns agonizingly black). She is as giddy as a child when she gets her hands on some junk food for the first time in months; she is a source of worry for Farsi when her anxious silences lengthen, or when she admits she has not eaten today; and she is a font of loving high spirits whenever she takes a call alongside one of her young relatives. “He’s never seen a woman like you, a foreign woman,” she explains to Farsi as a toddler stares wide-eyed at her phone.

Farsi offers platitudes she knows are inadequate, and Hassouna reassures her that her very presence, as a friend and witness and occasional provider of cat pictures, is comfort enough. The two bond over their experiences of oppression, though their biographies are not exactly equivalent, as Hassouna is under bombardment from an occupying government, and Farsi was persecuted and forced into exile by her own. She expresses sceptical curiosity about Hassouna’s choice to wear a headscarf, and probes for her feelings about Hamas—which, after all, is a proxy of the Iranian state that imprisoned her before her exile to Europe.

The dynamic between a Muslim Gen Z revolutionary and a secular Gen X liberal is one imbalance among several that will resonate with American audiences. Though the conceit of the film inverts Farsi’s life, pushing her everyday surroundings to the margins of the frame, it peeks through—she often calls Gaza while on work trips to international film festivals, or from a vacation. Hassouna seems to be excited at this, rather than jealous or resentful. Farsi’s self-conscious avowals that the two will go to this or that place together, someday, when the war is over, triggers a viewer’s awareness of his own privilege, but it is also evident that Hassouna takes Farsi more seriously because of her artistic lifestyle—that Farsi is living a life that Hassouna wants for herself, a life of freedom of movement and intellectual stimulation.

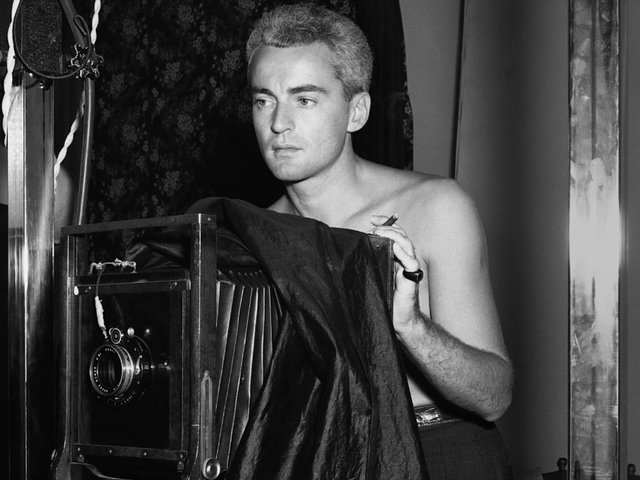

A still from Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk (2025) Courtesy of Kino Lorber

Farsi was fortunate to be connected to such a compelling documentary subject. Charismatic, thoughtful and yearning, Hassouna at times seems like the imaginative projection of sympathetic Westerners envisioning a perfect victim, though saying this diminishes the subjectivity evident in her considerable artistic talent. Hassouna wrote poetry and composed songs on her guitar before she sold it buy her camera, and what we hear of both is mournful and sophisticated, though Hassouna is adamant that she found her vocation in photography, even before becoming a photojournalist by necessity. She dreams of traveling abroad to learn photo editing technologies and study lighting.

“I try to find some life” Hassouna tells Farsi of her photos, which are reproduced in montages throughout the film. The life that she finds, in pictures frequently taken in the aftermath of bombings, is often a pop of colour against a backdrop of rubble: the T-shirt of a posing child, a defiant flag or flower, or rugs airing out on the balcony of a blasted-out apartment building. Later in the film, the colour is more frequently blood, pooling in the dust or staining a severed hand. The last shot of the cut of the film that was invited to the Acid selection of this year’s Cannes Film Festival is a long video taken during daytime, showing life persisting in a more than half-ruined city. On the soundtrack, Hassouna explains that she imagines her photographs will be a way to show her future children what she once endured.

It is a fitting ending, to which two scenes were amended before the film’s world premiere. In the first, Farsi calls Hassouna on the day of the announcement to share that the film has been accepted to Cannes—a festival Hassouna has heard of, and is eager to attend, if the passport and visa can be worked out, though she is clear that she would return home to her family afterwards. In the second added scene, a title card reveals that Hassouna was killed along with six members of her family by an Israeli airstrike the day after the Cannes programme was announced.

Some commentators have questioned the entire enterprise of Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk. Farsi got good reviews and a big premiere out of a film that almost certainly made its subject a priority target for the Israel Defense Forces. Then again, Hassouna had previously declared that, “If I die, I want a loud death”. It would be too simple to say that that was the contract she entered into with this film, but equally, a second title card reminds viewers that Israeli forces have killed hundreds of journalists in Gaza since their offensive began, many in targeted attacks. Hassouna made herself a target simply by picking up a camera. Or, really, simply by existing. The conditional tense of Hassouna’s “If I die…” today seems, horribly, quaint; the film at least fulfills the second clause.

Watch the trailer for Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk:

- Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk screens at the New York Film Festival, Lincoln Center, on 13 October and is available to stream on several platforms