William Kentridge’s award-winning chamber opera Waiting for the Sibyl (2019) makes its New York premiere this week in Brooklyn (until 11 October). The debut comes as part of the inaugural Powerhouse: International arts festival at Powerhouse Arts, a converted former power plant in Gowanus.

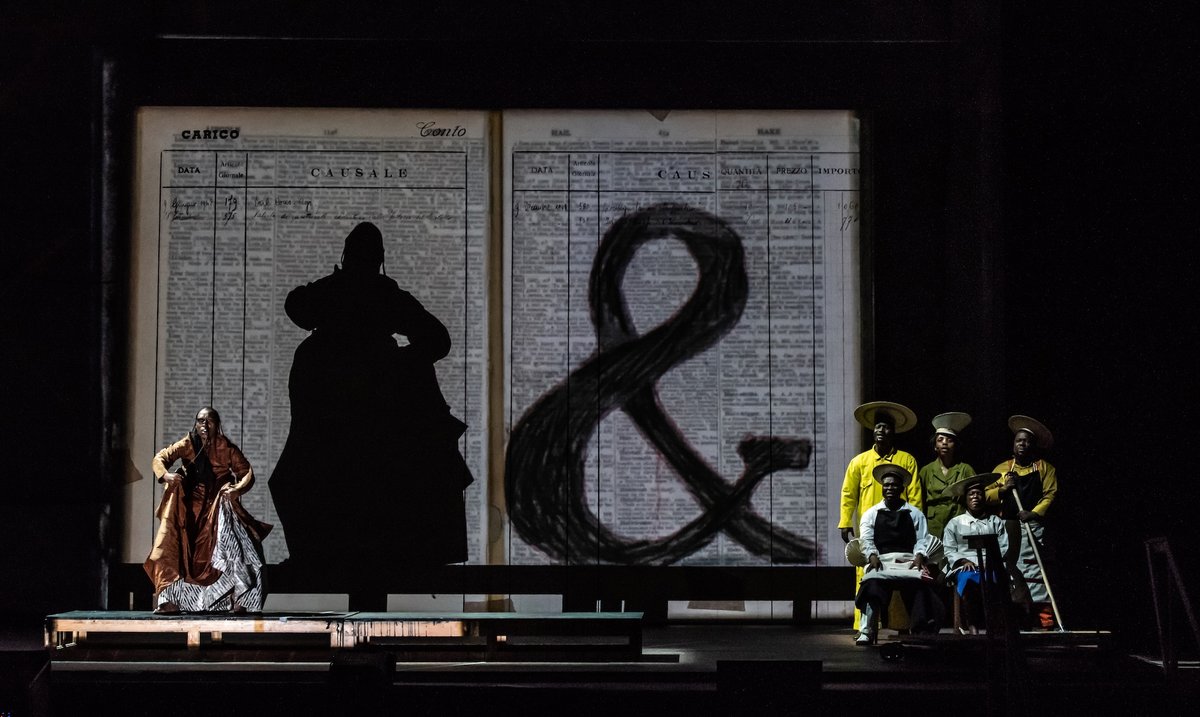

The international festival celebrates theatre, music, dance and other types of performance. Founded by David Binder, a former artistic director at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Powerhouse: International kicked off last month with a choreographed skateboarding performance and continues until mid-December. Kentridge's Waiting for the Sibyl features an original score composed by Nhlanhla Mahlangu and Kyle Shepherd making use of South African harmonies, plus an ensemble of ten singers and dancers performing amid a lively melange of the artist's distinctive animated ink drawings, collages, text projections and sculptures. In 2023, the production won an Olivier Award, British theatre’s highest honour.

The opera takes its inspiration from the oracles of ancient Greek and Roman legend—specifically, the Cumaean Sibyl, who resided in a cave near Naples and, when people came to her with questions about their future, would write the answers on oak leaves. The sibyl arranged the leaves outside the cave, but when a wind came, their inevitable shuffling meant that those who sought her answers could never be sure which leaf was meant for them.

Kentridge was intrigued by the myth’s poetic metaphor for life’s uncertainty and the ever-present question of fate. In Waiting for the Sibyl, leaves of paper—for example, from books like Dante’s Divine Comedy, which features the Cumaean Sibyl—symbolically blow through the action on stage.

The Calder connection

Waiting for the Sibyl was originally commissioned by the Rome Opera as a companion piece to Alexander Calder’s 1968 Work in Progress—a 19-minute “ballet without dancers” consisting of performers cycling onstage among an environment of mobiles and other kinetic sculptures to a score by three contemporary Italian composers. When Kentridge’s work premiered in September 2019, it was preceded by Calder’s short piece. A few months later, the world shut down due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

“One sees Waiting for the Sibyl differently post-Covid, but that's not because the production changed,” Kentridge tells The Art Newspaper. “It's because the world moved around it. There is a section called ‘Starve the Algorithm’ about what it is for the machine to be controlling our lives. The algorithm is a contemporary form of sibyl or oracle that predicts the weather, our likes, our dislikes, how long we will live, what diseases we're going to get.”

A performance of William Kentridge’s Waiting for the Sibyl (2019) Photo: Stella Olivier, courtesy Powerhouse Arts, Brooklyn

When the pandemic-era shutdowns ended, Kentridge thought it would be nice to tour Work in Progress and Waiting for the Sibyl together and perform them back-to-back, as they had been in Italy. (“Waiting for the Sibyl in some ways was a response to the Calder,” Kentridge says.) Unfortunately, even though the mobiles and stabiles used in Work in Progress are owned by the Rome Opera, “once they left the theatre, they weren't just theater props. They were artworks by Alexander Calder and obviously worth a fortune,” Kentridge says. “There was no way we could pay the insurance on that, nor could we transport them with the white gloves and air-conditioned crates that was the demand of such artworks and of the Calder Foundation.”

Kentridge came up with a solution to this problem. He would make copies of the Calder sculptures and tour with those instead. After all, the original mobiles and stabiles that feature in Work in Progress “weren't made by hand by Calder”, he says. “They were made to a drawing of his by the workshop in Rome. And when they needed it, they were touched up or repainted.” But, he says, the Calder Foundation said no. Kentridge found this extremely disappointing. “It’s a pity,” he says, “because chances are that this beautiful production of Work in Progress will never be seen again. Our chance to take it around was probably the only possibility.”

With the Calder piece unable to tour, Kentridge came up with a replacement to precede Waiting for the Sibyl. “In place of the 19-minute Calder, we have a 19-minute performance of The Moment Has Gone, which has different formal and thematic connections to the second part of the evening,” he says.

A brush with... William Kentridge

The Moment Has Gone, a film with live accompaniment by some of the same musicians who later appear in Kentridge’s opera, “is a piece primarily around a film called City Deep about mining in Johannesburg”, Kentridge says. “That and Waiting for the Sibyl were made at the same time in my studio. So the different drawings migrate from one project into another, phrases that were being used in Waiting for the Sibyl came into City Deep. Drawings of the sibyl make their way into the landscapes of Johannesburg. There are those moments of connection, but it is a separate piece.”

Now, The Moment Has Gone is an integral part of Kentridge’s performances of Waiting for the Sibyl—it always serves as the first section of the programme, with the opera as part two.

Although Kentridge is still somewhat peeved with the Calder Foundation, he has accepted the fate of his project. “In retrospect, it would have been impossible to continue the run of Waiting for the Sibyl if we'd had the Calder, just because of the logistical questions—the weight, the scale, the shipping, the containers we would need. It also needs trapdoors and fly bars, which not all the spaces we perform in have,” he says. “But my hope is that the Rome Opera will revive the double bill, so that the Calder can be seen again.” Only the sibyl could know if that will ever happen, but her answer will inevitably scatter in the wind before Kentridge can read it.

- Waiting for the Sibyl, Powerhouse Arts, Brooklyn, until 11 October. Powerhouse: International, Powerhouse Arts, Brooklyn, until 13 December