Ruth Asawa was what gamers like to call a world builder. Over the course of six decades, mainly from her small home in San Francisco, she transformed wire and other simple materials into an entire universe of fruiting forms and branching shapes.

And nowhere is her persistence and range of vision more apparent than the ambitious retrospective that opens at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) this week (19 October-7 February 2026) after its run at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA) this spring and summer. Nearly five years in the making, the show features 275 of her works, including more than 60 of the looped-wire sculptures she made famous as well as bronze casts, paper folds and a range of paintings and drawings that reveal her connection to nature.

In New York the show will occupy the 16,000-sq.-ft space on MoMA’s sixth floor used for big temporary exhibitions. In San Francisco, it took up 15,000 sq. ft on the fourth floor, combining two galleries usually used for different purposes. The SFMoMA illustrated checklist, with 327 pieces (including some ephemera), spans 81 pages. MoMA’s, with 376 objects (thanks to more archival material), is 94 pages.

By checklist alone, Ruth Asawa: Retrospective ranks as the largest show ever devoted to a woman artist at MoMA or SFMoMA. But neither museum has been promoting that fact for some expected and surprising reasons.

SFMoMA’s chief curator Janet Bishop, who joined the museum in 1988, says it had simply not occurred to her. “We knew that it was going to be a very rich, full presentation that looked at all aspects of her artistic production,” she says, “but I didn’t think about the sheer numbers.”

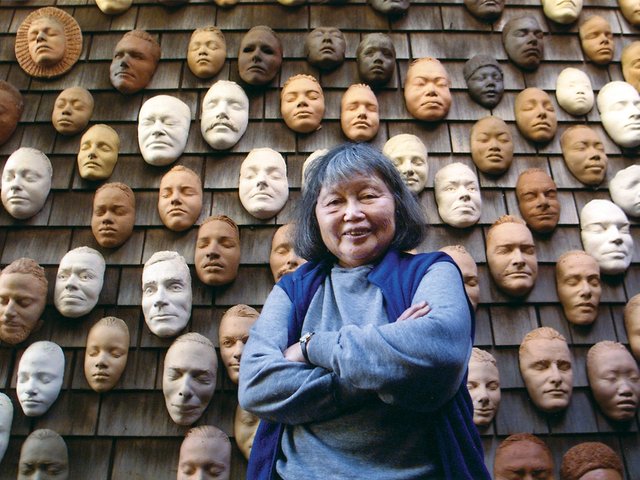

Installation view of Ruth Asawa: Retrospective at SFMoMA Artwork: © 2025 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc., courtesy David Zwirner; photo: Henrik Kam

Asked if any other show by a woman artist has come close, Bishop says no, noting that other solo shows in the same space, by artists such as Eva Hesse and Vija Celmins, had far fewer works. “The only shows that could have been larger are exhibitions that took multiple floors like Andy Warhol and Sol LeWitt,” she says.

Cara Manes, the MoMA painting and sculpture curator who co-organised the show, had a similar response. She ran through recent shows—Joan Jonas, Yoko Ono, Adrian Piper—out loud before saying, “I do think that’s a safe claim to make” and “you bring up a great point”. (A spokesperson for SFMoMA has since confirmed that its Asawa show was its largest by a woman artist measured by number of objects; MoMA declined to do so.)

Quiet confidence over shouted superlatives

To some extent, these curators seem to be taking their cue from Asawa by not establishing bragging rights for the show. Confident in her own direction as an artist, even in the 1950s when art critics called her a housewife and described her sculptures in decorative terms, Asawa was more collaborative than competitive with other artists. She was a longtime educator and six-time mother, often making art while cooking dinner or after everyone went to sleep, and she was not given to pissing contests. The arc of her career is marked by an honesty to materials, integrity to her vision and integration of artmaking into everyday family life.

To be sure, billing an exhibition as the biggest of its kind is a surefire way to inspire critics to try their hand at cutting it down, essentially inviting them to make a list of what the museum would have been smart to leave out or other artists who should have received similarly expansive showcases. But the lack of superlatives in promoting this retrospective, which travels on to the Guggenheim Bilbao and Fondation Beyeler in Basel in 2026-27, might also reflect a persisting gender inequality: how the art world still treats examples of male and female genius differently.

David Hockney, for instance, seems to have a "biggest retrospective" every five years, capped by the one at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris this year showcasing around 400 works. (At the same time, he likes to lampoon the art world’s inflated rhetoric, titling his latest gallery show at Annely Juda in London, opening 7 November, Some Very, Very, Very New Paintings Not Yet Shown in Paris.)

Picasso curators frequently compete to offer the largest display of his sculptures or drawings or biggest museum show period. This one-upmanship goes back at least to 1980, when MoMA gave over its entire 53rd Street home to an exhaustive and exhausting 1,000-work Picasso survey, which helped define the idea of blockbuster.

More recently, Jean-Michel Basquiat curators have been vying to see who can do the definitive mega-exhibition, with the recent bicoastal show King Pleasure billed as “the most intimate and comprehensive portrait of Basquiat’s life and art to date”.

The MoMA press release instead says of Asawa, more subtly: “Coinciding with the centennial of the artist’s birth, the exhibition will include some 300 objects that highlight the core values of experimentation and interconnectedness pervading all dimensions of Asawa’s practice.”

“We’re certainly happy to wave the flag of touting the comprehensive nature of the retrospective exhibition,” Manes says, calling it “staggeringly broad”. But, she adds: “Our framing had mainly to do with the exhibition being the artist’s first major career retrospective since her passing in 2013.”

At SFMoMA, Bishop likewise says her focus was not metrics but presenting Asawa’s work “in its full depth and breadth. She worked not only in wire but also paper, wood, clay and bronze. She experimented with electroplating. She filled hundreds of sketchbooks, a sustained drawing practice. She was a maximalist and a multitasker.”

According to Marilyn Chase’s biography, Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa (2020), the artist benefited from the fact that she typically only needed four hours of sleep. Manes says this is not just a myth. “When I was looking at works with some of her children, I would say under my breath, as so often was the case when being confronted with her incredible, prolific work: ‘How did she do this? How could she have had time to do this?’ They would say, ‘She just didn’t sleep.’”

The curator also found anecdotal evidence of this late-night productivity in Asawa’s archives. “She sketched constantly,” Manes says, “And these sketchbooks are peppered with images of other people sleeping.”