The British artist Joy Gregory has just opened her first institutional survey show at Whitechapel Gallery in London, enabled by winning the 2023 Freelands Award. The prize helps an institution put on a show of a mid-career female artist who has yet to receive the attention that her work deserves.

The result is Catching Flies with Honey, comprising more than 250 works across photography, film, installation, textiles, sound and digital media. The works have been produced over four decades of keen observation and experimental art-making. Gregory is a photographer who expands the idea of what a photograph can be and a keen listener to the patterns, rhythms and absences in daily life. Here she discusses her early forays into image-making, her ceaseless interrogation of what portraiture is and her new commission, 20 years in the making.

The Art Newspaper: You have spoken about always following the work, wherever it takes you. What has it been like to reel it back and revisit decades of your practice?

Joy Gregory: Very difficult. Because the first thing Gilane [Tawadros, the director of Whitechapel Gallery] asked me was, “Do you have an archive?” And I’m like, “What is this? Archive? It’s in drawers! Loads and loads of it! None of it is documented…” So I got a proper archivist to come in and document everything. The show contains about 40 years of work, even stuff from when I was at college.

In September I went to pick up a piece of work that I had made in 1999, a beautiful book that I’d completely forgotten about. I had made it while on a Triangle artist workshop at Plas Caerdeon in Wales. I met fantastic people from all over the world: El Anatsui, Suzann Victor… I had made the book out of salt prints of flowers, on slate tiles. I also made up names of plants then wrote a story and got everybody to donate their voice to this story, in their own language.

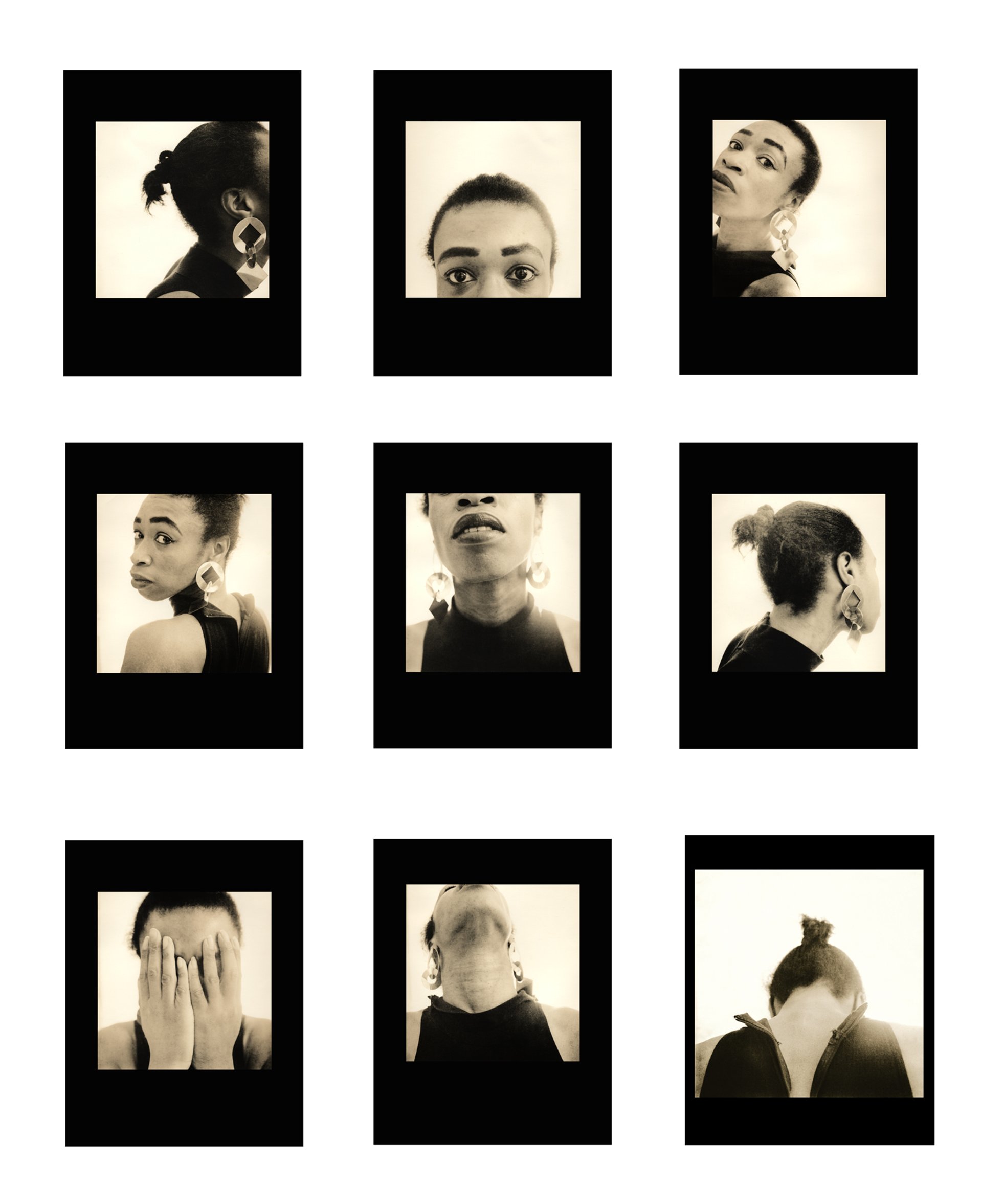

Joy Gregory’s self-portrait series Autoportrait (1989-90) © Joy Gregory; courtesy of the artist and DACS

Each work has led on to the next. My endangered language work in the Kalahari has been going on for decades, but then making that work in 1999 was part of me trying to make sense of it too. And the idea of self-portraiture, in Autoportrait, is also a really important part of taking pictures of other people. I think it is important to understand what it is to be on the other side of the camera: vulnerability, and how not to exploit it, is very important.

Even when I was at the Royal College of Art, in order to run away from John Hedgecoe’s daily tutorials, I ended up travelling all over the country, photographing people’s homes as portraits, without them being present.

South Africa is a place you have returned to repeatedly. How did that connection come about?

Until Nelson Mandela got out [of prison], I would never set foot in the place. I spent most of my youth protesting outside South Africa House [the country’s High Commission in London]. And then, of course, when Mandela was released, and became president, the country wanted to reconnect with culture. Lorna Ferguson had this fantastic idea to have a biennale. Sunil Gupta, who was running the Organisation for Visual Arts, invited me and a few other artists. The South African artist Clive van den Berg showed alongside us. I showed Objects of Beauty. It was a massive moment for me. I’d never really thought of myself as an artist.

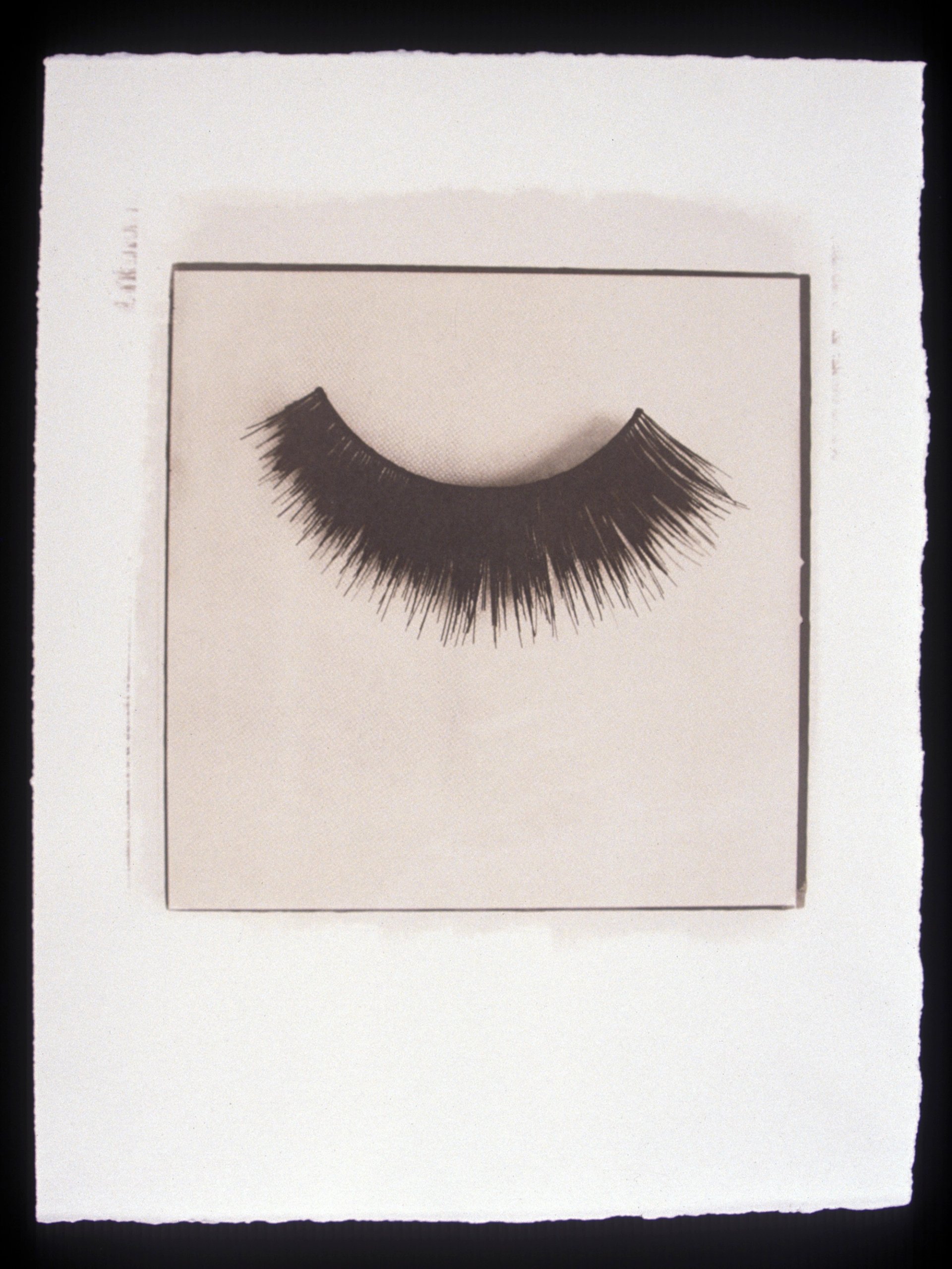

A kallitype photograph of eyelashes from the artist’s Objects of Beauty series (1992-95), which depicts items associated with beautification © Joy Gregory

The newly commissioned film, The Last Speakers, was shot in collaboration with a San community in the Kalahari Desert over 20 years. What was the impetus for that project?

While working on [the mixed-media installation] Memory and Skin in the Caribbean in the 1990s, I met an English-speaking community in Panama City, who took a huge pride in the fact that they identified as different through language. This idea stayed with me.

Then, in 2003 I went to a conference on endangered languages in Broome, in Western Australia, where there were lots of people from Indigenous communities who’d lost their languages and the connection with who they were. My forebears were enslaved. Not knowing exactly where I came from, or knowing that I come from lots of different places, this really touched me.

I heard about sisters Ouma |una and Ouma Khies, [two of the last N|uu speakers], through Nigel Crawhall’s presentation on the Kalahari and how the language was used for the first time in an historic legal case to win their land back. That touched me too, the idea of the burden of proof being on something that was not documented, that was transient, and that you couldn’t touch.

I flew to Upington in northern South Africa, to drive to Askham to meet the sisters. Everybody—all the language speakers—piled into the car. I suddenly realised I probably had more than half of the language population in my car, driving across the desert, and that if I had an accident, that I would wipe out a language in one fell swoop.

Joy Gregory’s Kalahari (Red Earth) (2005-10) © the artist

How did you figure out what shape the work would take?

I knew that I couldn’t make work straight away. I didn’t want to do additional harm. This community has been exploited by absolutely everyone. Most researchers were not people of colour. If they’d come from South Africa, they’d be fluent in Afrikaans. Even Magdalena, who worked as Nigel’s translator and had travelled, couldn’t get her head around the fact that I’d come from Europe. I think it was because I looked very much like somebody from the community.

Going back to 1995, on my first visit to South Africa, I had arrived in a wheelchair [because] I get hemiplegic migraines. I had with me this postcard of one of the Objects of Beauty images, of a bustier. The lady who was pushing me through customs couldn’t make any sense of it—she turned it round and round. And then I realised that not everybody has had the same experience in life as I have—that assumption that everybody sees in the same way.

When I went back in 1998 to do the residency at the National Gallery in Cape Town, I made Lost Histories. It really was about trying to cross a divide, thinking about how colonised people actually see themselves. As people in the community have died, I have realised what I was doing was watching a language die. People moved from speaking N|uu when I first was there, to Afrikaans and N|uu, to now the grandchildren and great-grandchildren, who speak English.

Having this show now, I felt it was a really good time to actually make the work. I owe it to all the people who had given me their time. I wanted to use pictures from the whole journey, with the voices I recorded on this last trip. It came together through doing the soundtrack. I worked with the South African composer Philip Miller, with whom I’d collaborated before on Seeds of Empire. It’s like an account, a conversation between me and the community. It’s about translation and trying to understand. For me, it was really important that it is their voice, telling their story.

• Joy Gregory: Catching Flies with Honey, Whitechapel Gallery, London, until 1 March 2026