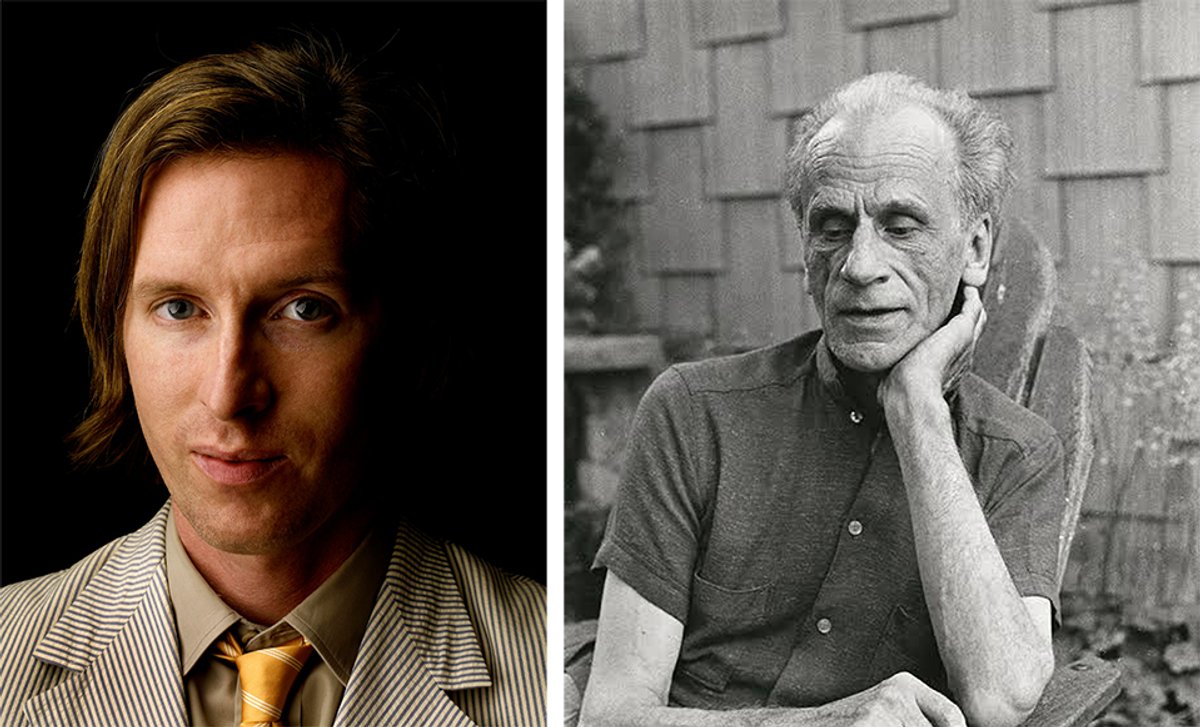

Wes Anderson’s films have frequently been compared to Joseph Cornell’s art— the meticulous attention to detail, the miniature nature of the tableaux they both create and the abundant art historical references. But Anderson has never publicly acknowledged Cornell’s influence on his film-making, until now.

Next month, to coincide with Christmas and Cornell’s birthday on 24 December, Anderson is recreating the artist’s New York studio in Gagosian Gallery’s storefront space on Rue de Castiglione in Paris. Around 12 of Cornell’s most recognisable works, so-called shadow boxes he hand-built from wood and filled with assemblages, will be exhibited alongside hundreds, if not thousands, of found objects—though visitors will not be able to enter the gallery.

“It’s essentially a window display,” says the exhibition's curator Jasper Sharp, who has worked with Anderson for several years, most recently sourcing original works of art for the director’s latest film The Phoenician Scheme. “And we’re doing it at Christmas, which was Cornell’s favourite time of year. His birthday was on Christmas Eve. Leo Castelli, Peggy Guggenheim, all his dealers gave him shows at Christmas time because they thought that his boxes made small, inexpensive Christmas presents.”

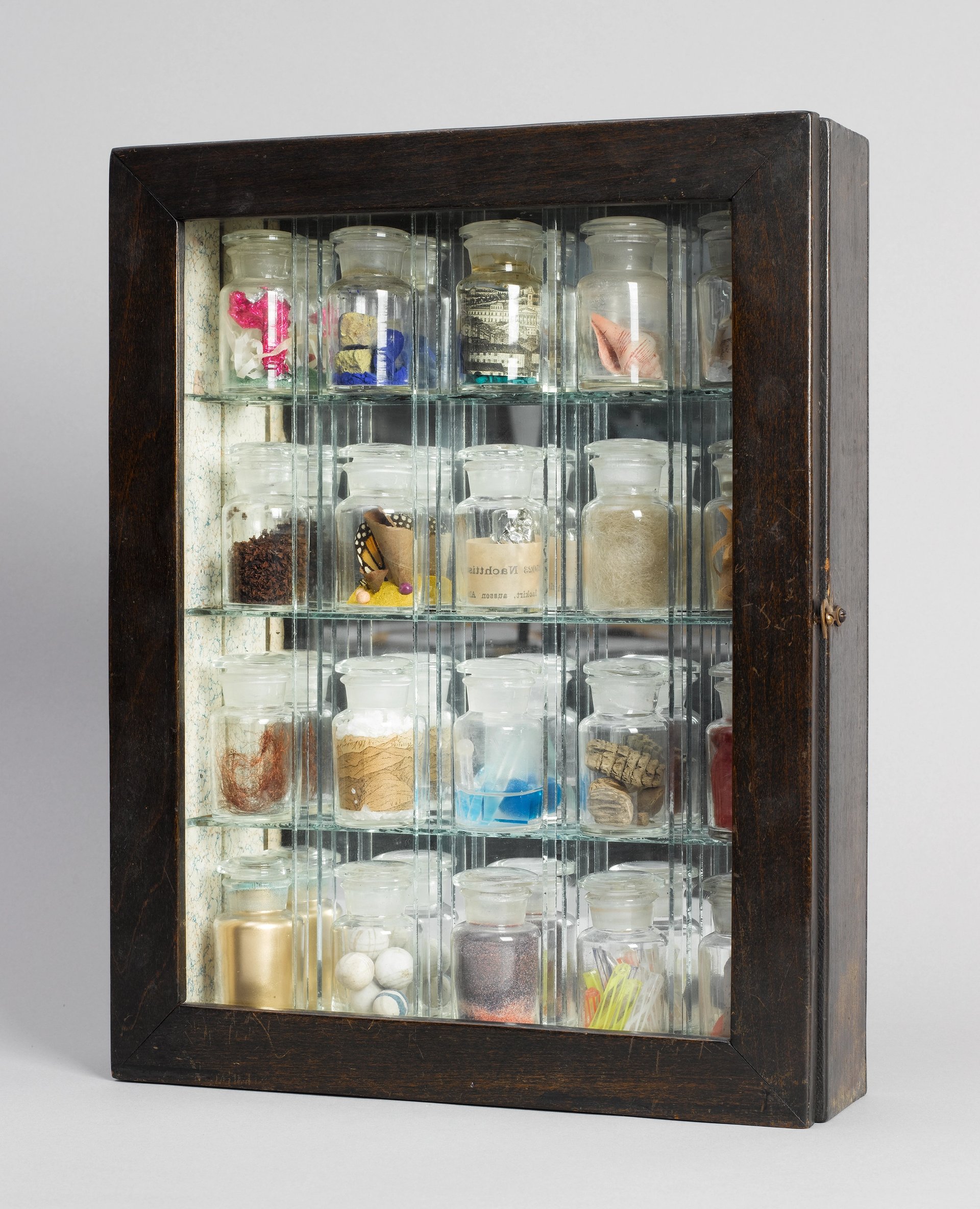

Joseph Cornell, Pharmacy (1943)

© 2025 The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Dominique Uldry. Courtesy of Gagosian

Among the main bodies of work on show are Pharmacy (1943), which was once owned by Teeny and Marcel Duchamp and is modelled after an antique apothecary cabinet. Other key pieces include Untitled (Pinturicchio Boy) (around 1950), a work from Cornell’s celebrated Medici series, and A Dressing Room for Gille (1939), which pays homage to Jean-Antoine Watteau’s Gilles (1721), in the collection of Musée du Louvre, a short walk from the gallery. Blériot II (around 1956), meanwhile, honours Louis Blériot, the French inventor who was the first person to make an engine-powered flight across the English Channel.

“The rest of it,” Sharp says, “we’re reverse engineering.” He and Anderson have spent weeks studying first-hand accounts of the atmosphere at the studio, as well as poring over photographs. “We’re basically doing what Cornell did, going to flea markets and buying what he bought,” Sharp says. “For example, there’s this wonderful wall of whitewashed shoe boxes where Cornell kept all his seashells and driftwood and different things. We are recreating these boxes ourselves.”

The sign painters who work on Anderson’s films have studied Cornell's handwriting and will write on the ends of all the boxes. Another movie expert is helping to age some of the materials. “It’s not an archaeological excavation or one-to-one model of Cornell’s studio, we’re primarily recreating the spirit and atmosphere. But Wes also didn’t want it to look like a Wes Anderson show. He hasn’t done his version of Cornell’s studio,” Sharp says. The exhibition coincides with a show of Anderson’s archives, which opens at the Design Museum in London on 20 November.

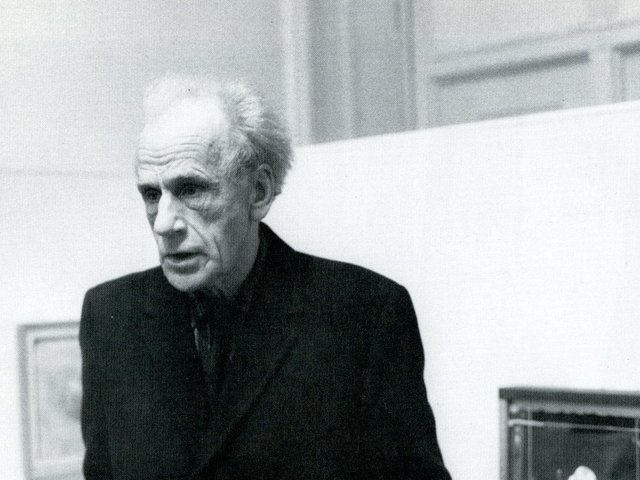

With no formal artistic training and having worked a string of blue-collar jobs to support his family after his father died young, Cornell was 37 when he decided to become a full-time artist. It was then he built a studio in the basement of the home he shared with his mother and brother in the Queens neighbourhood of Flushing, setting up a workbench, several tables, cabinets and a series of shelves on which he stored the objects he collected. Cornell also continued to work in the house—in the garage or at the kitchen table. “He’d bake things in the oven to age them and give them a craquelure,” Sharp says. “But very few people were actually allowed down into the studio.”

Joseph Cornell’s studio in the basement of his family home in Queens, New York, 1971

© Harry Roseman, Wes Anderson

The few who visited were of a certain calibre: Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning, Yayoi Kusama, who Sharp says was Cornell’s girlfriend for a time. Andy Warhol, who bought a piece, and Robert Rauschenberg as a young art handler, who went to collect Cornell’s work for an exhibition. Other visitors included Susan Sontag, John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Billy Wilder and Tony Curtis.

Precisely because Cornell’s studio was largely invisible to the world, and preserved only in black and white photographs, Sharp says he and Anderson “thought it would just be beautiful to bring it to life—and in a city that he dreamt of his whole life but was never able to see”.

Cornell, a recluse who was also a Christian Scientist, experimental filmmaker and self-declared magician, rarely travelled further than a subway ride into Manhattan. “I think he was very shy. One of the very last things he said before he died was, ‘I wish I had not been so reserved’,” Sharp says.

Nonetheless, having read guidebooks and collected postcards, “Cornell knew Paris like the back of his hand”, Sharp adds, pointing to an account of one of his first conversations with Marcel Duchamp, with whom Cornell had a longstanding friendship. “During this conversation, they wandered around Paris for about 30 or 40 minutes and at the end of the conversation, Cornell said, ‘I’d love to go to Paris one day’. Duchamp was just astonished that this person had a photographic memory for a city that he'd never seen.”

It is exactly this precision that drew Anderson to Cornell’s work. Sharp notes how the same approach to detail was how he came to work on The Phoenician Scheme, sourcing works including a Renoir from the art collecting Nahmad dynasty and several masterpieces from the Hamburger Kunsthalle. “There was nothing gratuitous about [securing the loans], it was completely consistent with Wes’s approach to detail and an approach to just extract everything he can from a particular situation,” Sharp says.

He points to the scene where Mia Threapleton, who plays Liesl, is woken in bed by Benicio del Toro shining a torch in her face. Del Toro plays arms dealer and art collector Zsa-Zsa Korda. “Mia is wearing a vintage nightgown, she’s sleeping on a mattress that’s been stuffed with horsehair, then there's an original Renoir painting behind her. The whole scene is set up so intricately with beautiful materials, textures and original things that it's going to elicit a different performance from her than if everything is made of balsa wood,” Sharp says.

As for staging the Gagosian show, with so many objects to bring together, Sharp says he and Anderson are now doing a test build of Cornell’s studio in a warehouse on the outskirts of Paris. But, despite the rigorous preparation, there is still an element of chance with the installation. As Sharp puts it: “Lot of things will be in flux until about an hour before the door opens, that’s just the nature of the beast.”