“All good Americans when they die go to Paris,” remarked Thomas Gold Appleton (1812-84), the notorious Boston wit and unrepentant snob—a quip American artists of the period would have amended to say, “All good American artists go to Paris”, not to die but to live! There was one problem, however, and that is the subject of art historian Jennifer Dasal’s enjoyable The Club.

If you were a female artist in turn-of-the-century America, it was harder to pack your bags and move to France than for your male counterparts, such as Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) or, for that matter, the amateur painter Appleton. “I was brought up to believe that matrimony was the desired end of a woman’s life”, sighed Anne Goldthwaite (1869-1944), an aspiring painter from Montgomery, Alabama. There were other obstacles, too: the French capital was rumoured to be a mecca not only for artists but also for brazen pickpockets. And then there was the sheer expense of living.

Salon dreams

Enter Elisabeth Mills Reid, the wife of Whitelaw Reid, the US ambassador to France. In 1893, Reid opened the “American Girls’ Club” in a rambling property in Montparnasse. Originally built as a porcelain factory, for two decades 4 Rue de Chevreuse offered a safe home (and affordable meals) to some of the brightest female talents in American art. The members of “the Club” rose early and worked hard during the day, hoping to achieve their life’s dream of inclusion in one of the famous annual Parisian art shows, the “salons”. Goldthwaite’s 1908 painting, now at the Whitney Museum of American Art, of three colourfully dressed women conversing in the leafy, cobblestoned courtyard summed up what residents could expect at 4 Rue de Chevreuse: companionship, some cats to pet and a servant delivering the afternoon tea.

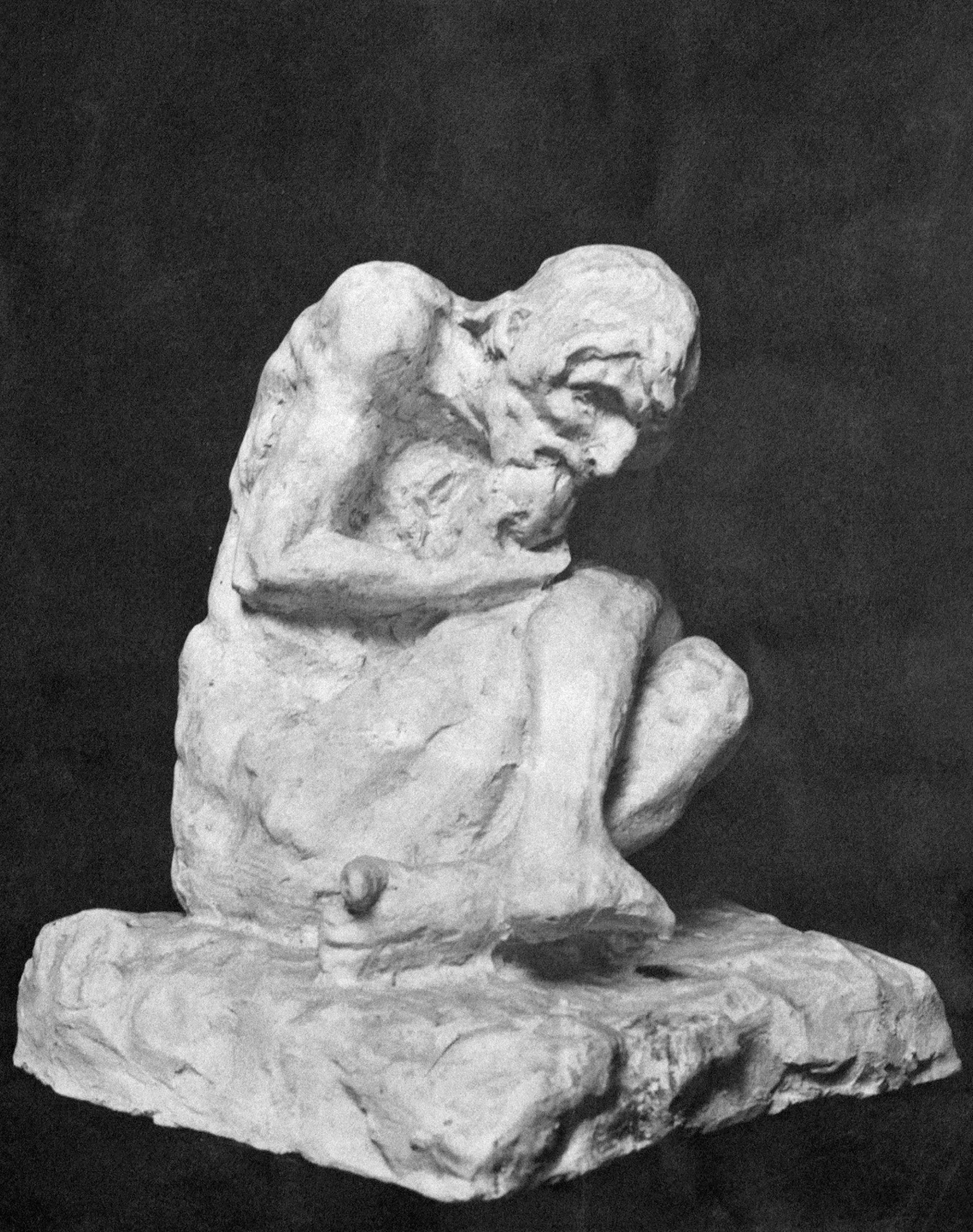

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s Man Eating His Heart (around 1900)—the mixed-heritage sculptor did not gain entry to the Club but did exhibit in its annual show Courtesy of the Danforth Art Museum of Framingham State University, Gift of Carnel Hoover

Some of these women did not simply seize what Paris had to offer; they returned the favour. One of Dasal’s loveliest chapters portrays Florence Lundborg (1871-1949) from San Francisco, who, with her blonde hair piled high, decorated the walls of her favourite Parisian crémerie in exchange for food. Others fared less well: Gertrude Weil from Philadelphia, a frequent guest at the Club, worried her friends with fits of despondency; she was found drowned in the Seine. Jessie Allen, from Albany, New York, known for her skilful sketches of Venice, died after a cycling accident. And not everyone was welcome, as Meta Vaux Warrick (later Fuller, 1877-1968), a Black sculptor from Philadelphia, found out the hard way when, on arrival, the Club’s director refused to give her a room, declaring, “You didn’t tell me that you were not a white girl.”

But Warrick had the last laugh, as Dasal notes with satisfaction. Her work attracted the attention of Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), who pronounced her a sculpteur née (a born sculptor) and volunteered to mentor her. It is no wonder that Warrick’s Man Eating His Heart (around 1900, location unknown) caught Rodin’s eye: a man collapsed to the ground, only recognisable as human because he has eyes and a nose, in desperation feeds on himself. Although Warrick never lived at 4 Rue de Chevreuse, her work did make it into the Club’s annual show of women’s art.

Contributions of a similarly high quality came from another sculptor, Alice Morgan Wright (1881-1975), who left the comfort of the Club to join her idol (and love interest), the leading English suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst at a protest in London and was promptly thrown in Holloway Prison—an experience that did not faze her. As a young artist in New York, prevented from taking part in life-drawing classes, Wright hung around athletic clubs to get up to speed on human anatomy. Her Wind Figure (around 1916, Hirshhorn Museum) makes the bronze come alive: a genderless, foreshortened torso becomes a spiral.

Fading memory

The First World War put an abrupt end to the Club’s activities. Renamed Reid Hall, 4 Rue de Chevreuse today provides classroom space for American students abroad. The Club has become a fading memory: Modernist art, with its emphasis on in-your-face abstraction, left little room for the more intimate works by the Club’s women. But Dasal’s survey resurrects the spirit that animated them. Written in breezy prose peppered with the occasional French exclamation (Mon Dieu!, Quelle horreur!), The Club is itself a bit like the paintings of the artists of 4 Rue de Chevreuse: light and airy, with dashes of colour in just the right places, suffused with the creator’s enthusiasm for her subject. It is appropriate that, having come to the end of her book, relaxing in Goldthwaite’s leaf-shadowed courtyard, Dasal raises a celebratory glass of vin rosé to her women artists. There is, to be clear, a more serious message embedded in her cheerful storytelling: the sheer courage of the Club’s residents, their insistence that they are not barred from opportunities claimed by men, has lost none of its relevance.

- The Club: Where American Women Artists Found Refuge in Belle Époque Paris, by Jennifer Dasal. Published 15 July by Bloomsbury, 336pp, 99 black and white and eight colour illustrations, $29.99