How do you ‘read’ a painting? Can a painting even be read at all? I was invited to discuss this by the writer James Marriott on his podcast Cultural Capital. Like many gallery visitors, Marriott wondered if we need some kind of instruction to look at art and understand it. My answer was unhelpful: yes and no.

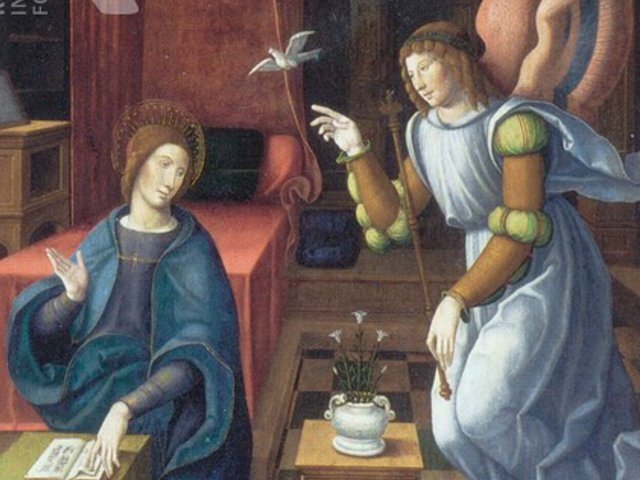

Our quest to understand art begins with a challenge, as a gallery encourages us to see art artificially. We are presented with a mass of paintings stripped from their original context. In the National Gallery in London, up until the 18th century probably most of the art on display was made to hang in a religious setting. The deep beliefs of the people looking at such pictures meant they were subconsciously understood as much as read. Without that context, and presented didactically as elements in the story of art history rather than faith, such paintings can appear puzzling, even off-putting.

Living context

The most moving art experience I ever had was being shown Giovanni Bellini’s Frari Triptych (1488) in Venice by the priest of that church. As far as he was concerned, the painting was first and foremost a tangible representation of the Son of God, the Virgin Mary and the saints around them. The painting represented his faith and reinforced it. Hanging in the same place it was made for and in its original frame, it was as fresh and purposeful for him as it had been for his predecessors over 500 years ago.

A modern example is Banksy’s recent graffiti on the side of the Royal Courts of Justice. The image of a placard-holding protestor being beaten by a gavel-wielding judge is interpreted by its audience with ease. Days before, hundreds of protesters in London had been arrested for supporting the controversially proscribed organisation Palestine Action. We know what Banksy’s image is about, because we are living the context in which it was made. But if we were to live 200 years hence, and Banksy’s image was hanging in a gallery, the task would be harder. Any label hanging beside it would have to explain every aspect of the image, from gavels to Gaza. And who knows what the political environment might be in the future? Will protest as a concept exist?

Changes of approach

It is also surprising how frequently art historical methods of interpretation change over time. For those like Ernst Gombrich, whose brilliant The Story of Art was published 75 years ago, the first purpose of interpretation was aesthetic, discerning styles and attributions as a means of ordering the canon of art history. I am generalising, but it was more about looking at pictures than reading them. The reaction against this approach, beginning in the 1970s, saw new methods of interpretation emerge as scholars became more interested in art’s wider contexts: social, economic, political, gender and so on. Reading a picture became a means to understand the broader history of the time.

The latter approach has many merits but is vulnerable to subjectivity, especially when it comes to politics. For Marxist art historians such as John Berger, the true nature of the capitalist past is there for us to see in art, and it reflects the present. “If we can see the present clearly enough,” he said, “we shall ask the right questions of the past.”

I prefer my art history to be less about today. That’s why my first advice to anyone wanting to know how to read a painting is to understand the context in which it was made, not the context in which we see it. Sometimes, the best way to understand the past is to forget the present.