Art in Pakistan, like its culture and language, has never quite fit the nation state that now contains it. Instead, it arises from the visual traditions of the Indian subcontinent and the Islamic world, passed through the refining fire of global modernism and the productive alienation of political trauma.

No one exemplifies this better than Shahzia Sikander, born in Lahore a generation after the Partition of India (1947) and moving on to the international stage in the years before 9/11. Alongside her near-contemporary Imran Qureshi, she is one of the best-known artists of Pakistani origin alive today. Both are known for their contemporary miniatures, a genre almost uniquely associated with Pakistan and particularly with the National College of Arts (NCA) in Lahore, one of the oldest art schools in Asia.

In the mid-19th century, the British endowed Lahore with a museum and an art school: they knew art was a potent expression of power. First, they razed Delhi and Lucknow to the ground; then they taught Indians to paint, print and sculpt. The aim was to preserve the aesthetic history of the subcontinent while inculcating “modern”—and therefore Western—ways of making art. In the leafy quadrangles of what was then Lahore’s Mayo School (until 1958), artists were taught on the Kensington model, while the wonders of Agra and Gandhara were arrayed next door in the Lahore Museum—the Ajaib-Ghar or “Wonder House”.

Old and new align

The NCA, Pakistan’s premier arts institution, was key to the fertile artistic milieu of the 1960s, bringing together pioneering Cubists like Shakir Ali (1916-75) and traditionalists like Haji Muhammad Sharif (1889-1978), the former court painter of Patiala who could trace a direct lineage of ustads, or teachers, back to the traditional workshops of the Mughal emperors. Today if you stand in the museum’s picture gallery, you can see before you the lines and shades of Ali in dialogue with the work of his contemporary Zainul Abedin, who came from what is now Bangladesh, and trained in one of undivided India’s other great art schools, the Government College in Calcutta. On the other side of the room, you will glimpse the indigenous, syncretic revivalism of the Bengal School of the early 20th century, which blended the Mughal past with the influence of Japan and London and the flat Ganges delta. It was from this wide nexus of influences that the contemporary miniature sprang.

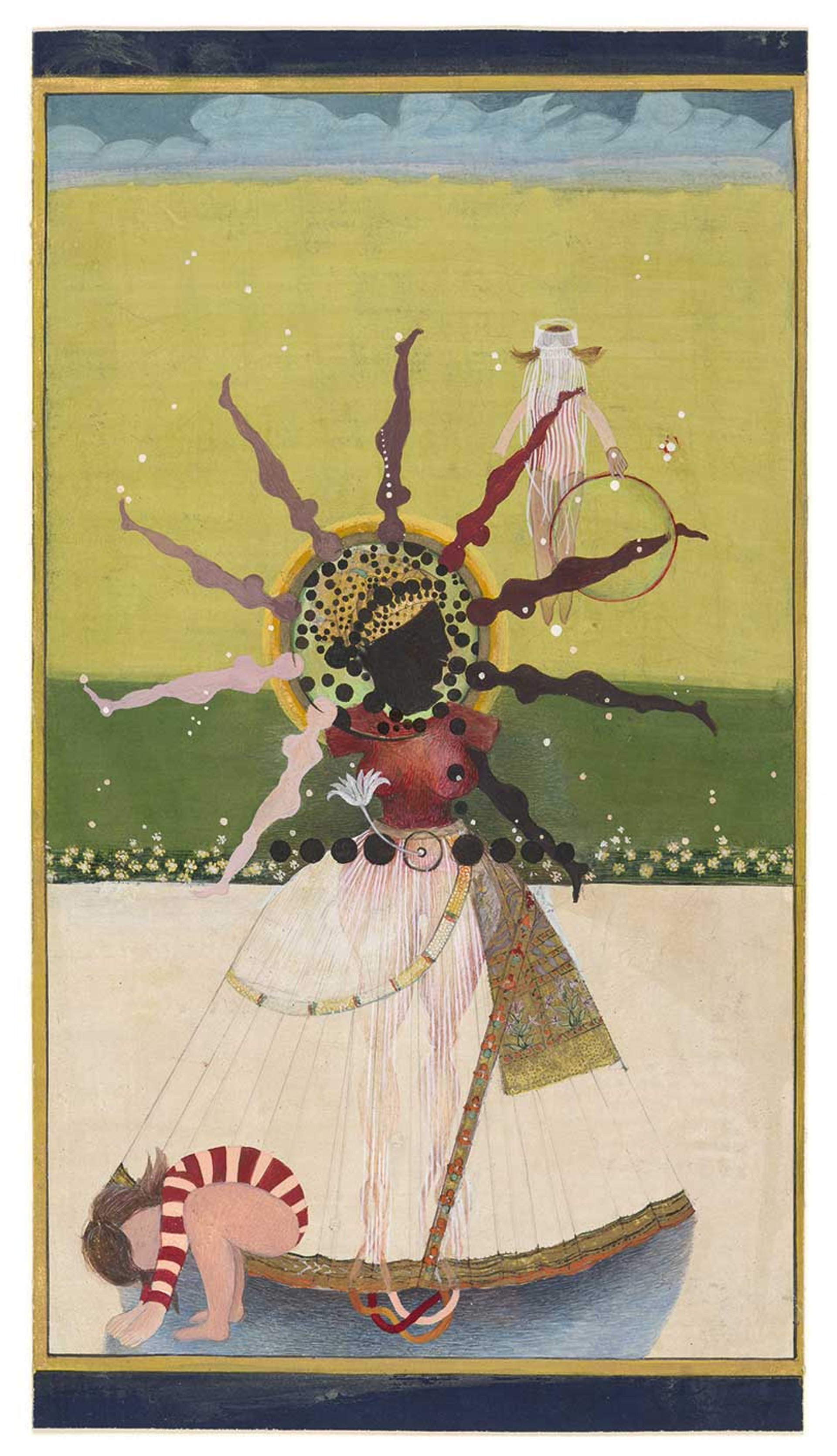

Shahzia Sikander’s Cholee Kay Peechay Kiya? Chunree Kay Neechay Kiya? (What Is under the Blouse? What Is under the Dress?) (1997)

Courtesy Cincinnati Art Museum

Artists like Zahoor ul Akhlaq (1941-99), who had pored over his cultural patrimony while studying in London, began to take traditional genres in new directions, playing around with the form and texture—as well as the purpose and meaning—of Indo-Persian miniature painting. Shahzia Sikander took it a step further. In her NCA graduate thesis, a 5ft-long painting on burnished wasli paper, named The Scroll (1989-90), she asserted that visual traditions could have searing personal and political salience.

In this handsomely illustrated monograph, art historian Jason Rosenfeld picks up the story. General Zia ul Haq’s American-backed, Islamic-tinged military dictatorship of 1980s did lasting damage to state and society in Pakistan, but it provided much inspiration for the country’s creatives. The Scroll depicts a woman wandering through domestic settings in a continuous narrative. The buildings, cut away in jagged sections, imitate the stylised architectural fantasies of Timurid painting. But, as the eye follows the dreamlike protagonist in her virginal white, the architecture takes on an oppressive air, showing, as Rosenfeld puts it, “the cramping reality… instability and oppressiveness” of General Zia’s Pakistan, where, for the first time, a woman could be flogged for adultery.

Rosenfeld writes that The Scroll “definitively kick-started the Neo-Miniaturist movement”. This may overstate the case, although the work certainly deploys a broad frame of reference—encompassing Herat and Siena and Sikander’s near-contemporary, the Indian painter Nilima Sheikh—in the expression of layered social and psychological truths.

Sikander has taken that fluid, multi-dimensional approach to everything she has done since, abandoning the more formal conventions of miniature painting in works in different media, which challenge our perceptions of history and aesthetics. Her work has drawn on everything from the British East India Company to hip-hop, Muslim womanhood and imperial America, Rubenesque white flesh and the Gopi maidens of Hindu painting in the Punjab.

Command of line and tone

The touchstones of her career have been the virtuosic reworking of visual references and a productive, vital tension between form and meaning, conveyed through total command of line and tone. Rosenfeld brilliantly describes the unique cachet of Sikander’s mature work: the “miniature precision” and “equally evocative looseness of the ink” in works on paper, where the familiar figures of 500 years of Indo-Persian art melt imperceptibly into swirling depths of water-coloured nuance. For Rosenfeld, Sikander’s work “mimics the way we see the world—ever in flux, never static, comprised of many discrete parts”.

Sooner or later the postcolonial artist must confront the question of identity. How is her work connected with history and tradition and all the labels of belonging that are stubbornly affixed to her name? Or should she, rather, eschew the reductive obligations of “authenticity” and assert herself on the unbounded stage of contemporary art? Sikander’s work has remained true to its roots, but transcended, challenged and deconstructed them. Here, the determining imprint belongs firmly to the artist herself.

- Jason Rosenfeld, Shahzia Sikander, Lund Humphries, 144pp, 100 colour & b/w illust., £45 (hb), published 18 November

- Cyrus Naji is a freelance writer and journalist