The second Lahore Biennale unfolded across Pakistan’s most cosmopolitan city at the start of 2020. At the opening, guests filled the broad forecourt that separates the finest mosque in South Asia from the stout walls of an ancient fortress where you will find the mirrored pleasure domes of the Mughals and the hallowed dungeons of their successors. Elsewhere in the city, the red-brick ramparts of British Lahore played host to subtle installations on themes like colonial erasure or sexuality in an Islamic Republic. Barbara Walker stencilled African subalterns of a colonial army on the walls of Tollinton Market, where the bookish imperialist John Lockwood Kipling curated Lahore’s first museum in the wake of the Indian “Mutiny” of 1857 and its bloody suppression. And at Bradlaugh Hall, what the Pakistani artist Salima Hashmi calls “the crumbling skeleton of a once-noble urban establishment” echoed with “the wistful sound of the desert”, courtesy of the folk musicians of the Bheel: a marginalised tribe from the Great Indian Desert whose stragglers have reached the southern Pakistani province of Sindh.

Subversive sensibility

In Pakistan, the state may not be fair or functional, but the arts continue to thrive, thanks in part to figures like Hashmi who keep alive a subversive artistic sensibility through the patronage of independent-minded institutions. The Lahore Biennale is one of the newest and most successful of those institutions. Running to three editions so far, years of work in dozens of countries went on display for just over a month, in 2018, 2020 and 2024. Skira’s voluminous new Lahore Biennale 02 Reader, carefully edited by the Emirati Sheikha Hoor al Qasimi and the Cornell University professor Iftikhar Dadi, builds on those impressive foundations.

The book is a compendium of the ideas brought up in the 2020 biennial and features reflections on some of the works on display, alongside essays that continue themes discussed in the biennial’s academic forum. For example, the Ajam Media Collective—which takes its name from an early Arabic epithet for the Persians—brought Iranian researchers to Lahore, where they explored how centuries of shared cultural and historical identities continue to affect cities like Lahore, Tehran, Isfahan and Delhi: all important nodes in a Persianate world that cannot easily be written off as a defunct antiquarian curiosity.

According to the Reader, that workshop discussed the “push and pull of state and local forces” at Sufi shrines in Iran and Pakistan, which have a long history “as sites of refuge as well as danger in the Shia tradition”, while the anthropologist Seema Golestaneh now contributes a sensitive essay on the creative and subversive ways in which young Iranians relate to Sufism while living under a police state. Unable to organise formally, these latter-day mystics use song and the naked voice to convene neighbourhood meetings, which they regard as “something fun or cool (ba-hal) in the path of Sufism (darvishi)”. It is common to hear Iranians and Pakistanis say that the crimes wrought by state and society in the name of religion have driven them away from God, but here Golastaneh affords a glimpse of how ancient traditions and the human instinct for the divine can survive the ravages of authoritarian religiosity.

Unquenchable thirst

Always engaged with its environment, the biennial featured a multimedia installation called Indus Water Machines by the Pak Khawateen Painting Club, a collective of female artists, which, according to the Reader, focused on “people who are united around water bodies” in a country that cannot get enough water. The artists’ essay here tells us how they travelled to Pakistan’s wild, “ungovernable” Kohistan region, nestled in one of the outer valleys of the Hindu Kush, where they encountered tribal chieftains struggling to protect a way of life threatened by multiple levels of insecurity. Cut off for centuries in their mountain fastness, “the vacuum was a catalyst for developing unique cultures and dialects, but now the original tongue is diluted with Urdu words”, and dams needed for the subsistence of their downstream countrymen threaten to inundate their pastures and villages. In one instance, the Kohistanis have had to relocate “so far from the village that they are perpetually in a state of liminality with a language, climate, and terrain change”.

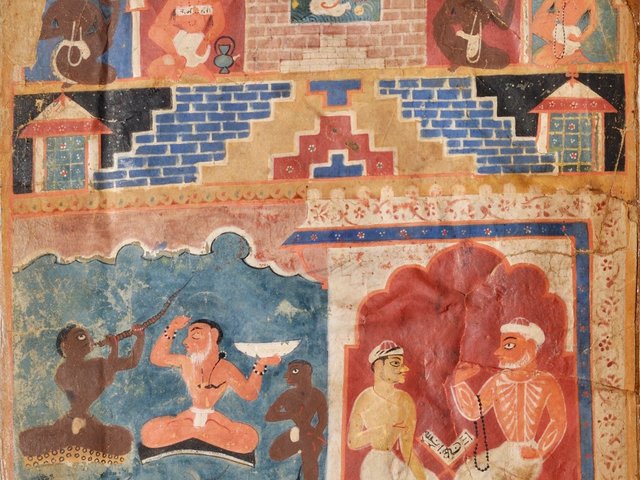

One of the volume’s particular strengths is its consistent grounding in historical and social reality; there is no mute aestheticism here. Its inroads to history have wide contemporary relevance: Devika Singh probes the reception history of Indian art in the dying days of empire. We learn how, as the Indian subcontinent was rent asunder in 1947, manuscripts were partitioned in the Punjab, while the new independent nations contested cultural identity under the influence of orientalism and nationalism. Was “Indian” art a broad umbrella, without sectarian significance, that could accommodate a varied nexus of influence, or was it a solid, unified category that would exclude all that was Iranian or central Asian? In an ever more parochial world, the question remains relevant: Hindu revivalist attitudes towards Mughal art mirror, for example, the complex, contested reception of ancient Hindu sculpture in Muslim-majoritarian Bangladesh.

The Lahore Biennale has so far achieved authenticity that is neither ossified nor simplistic, showcasing Pakistan’s artists and its culture, but not in isolation. The Reader provides a comprehensive intellectual underpinning for that diverse and deeply interconnected artistic world.

• Iftikhar Dadi and Hoor Al Qasimi, Lahore Biennale 02 Reader, published 27 March by Skira Editore, 532pp, illustrated, £45 (pb)