In October 2013, Kerry James Marshall opened an exhibition at M HKA, the museum of contemporary art in Antwerp, Belgium. The show, which was the artist’s most substantial presentation in Europe to date, went remarkably unnoticed in the Benelux region. Twelve years later, the same artist was heralded by the leading conservative art critic in the Netherlands as the “best painter alive” for his show at the Royal Academy of Arts in London (until 18 January 2026).

Artists including Emilia Kabakov are asking for the return of their works

That M HKA doesn’t get a mention in this review is revealing. Until now, the museum has played a role in the middle ground, a “development laboratory”, in the words of Bart de Baere, its outgoing director. That position seems to have become untenable as, in October, the Flemish ministry of culture instructed the museum to be closed, and its collection transferred to the S.M.A.K. in Ghent. The ministry also cancelled a €130m planned new building for M HKA that was ready to break ground.

What will be lost if M HKA disappears? Its programme is not one of spectacle nor hype that politicians and the media like to embrace. Rather, it serves a crucial role in linking emerging and established forms of art. Its collections are modest, often archival, embracing ideas such as Eurasian internationalism whose time is yet to come. It has organised seminal exhibitions on artists including Jimmie Durham and on local (but non-Flemish) practitioners such as Otobong Nkanga, Laure Prouvost, Dora García and Nástio Mosquito. It is a founding member of the L’internationale, a European confederation of museums, arts organisations and universities that has tried to shape a contemporary trans-European cultural vision.

Now a passionate rearguard action has been launched by artists and cultural workers in Flanders under the banner “Museum at Risk”. Its members occupied the museum’s entrance for 24 hours and have pushed Antwerp city councillors to stand up against the Flemish government and the Socialist Party, which were behind the move. Meanwhile, international artists including Emilia Kabakov and the estate of Christian Boltanski are asking for the return of their works or their deletion from the museum’s collection website—pieces they believed belonged to Antwerp and its citizens. These are heartening steps that show a community and city in need of a museum. Yet the danger is that, if successful, things will only return to the status quo ante—a situation that few were content with in the first place.

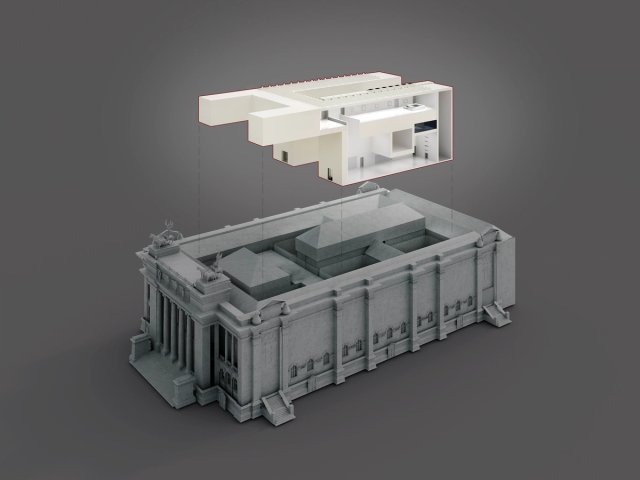

Ten years ago, de Baere and his colleagues embarked on a mission to build a new building to address the shortcomings of the museum’s current space. The building is far from ideal, its storage depot is totally inadequate, its collection management in need of better resources. In general, M HKA has always had the air of a temporary home looking for a permanent solution. Now, all the protesters are able to demand is the preservation of this inadequate state of affairs and de Baere himself has stepped back from such a scenario.

Looking back over the past three weeks of action and reaction, it appears the political decision largely revolved around the new M HKA building. By “liberating” the construction budget, Caroline Gennez, the culture minister, may have got her hands on enough money to satisfy various small-scale demands and to support her pet projects. The political commitment to a big gesture and a new museum seems to be simply beyond her civic-political imagination. Unless that decision is reversed, M HKA is unlikely to thrive.

This is where Flemish particularities meet broader western European forces. M HKA’s position can only be defended if the financial enablers of the cultural sector view their support as part of a wider ecosystem of care and sustenance. In this way, art is not instantly translatable into social or economic benchmarks. At the political level, this means elected ministers and civil servants need a vision of supporting culture without demanding instant accountability. It also means allowing cultural institutions and collections to find their resonance over time. These principles were present in western Europe from around 1960 until today. Now, they are dissolving into populist, neoliberal and politically clueless fragments. The case of the disappearing museum is therefore unlikely to be confined to Antwerp.

• Charles Esche is a curator, writer and professor of contemporary art and curating at Central Saint Martins in London. He is the former director of the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, the Netherlands