Consider Hans Holbein the Younger’s portrait of Henry VIII’s fourth wife, Anne of Cleves: an enigmatic look, cast from beneath heavy-lidded eyes; a long nose, the soft breath from which is almost felt; a red velvet gown richly adorned with gold and pearls, set against a blue background made more vivid by its recent restoration. Serving as the cover image for Elizabeth Goldring’s biography, it is a painting that conveys much of her subject’s continuing fascination: the eye-popping persuasiveness of his work; its ability to define an era in our cultural memory, and its enduring mysteriousness. For despite all their apparent credibility, Holbein’s sitters remain strangely alien, plucked from a past we can never properly know.

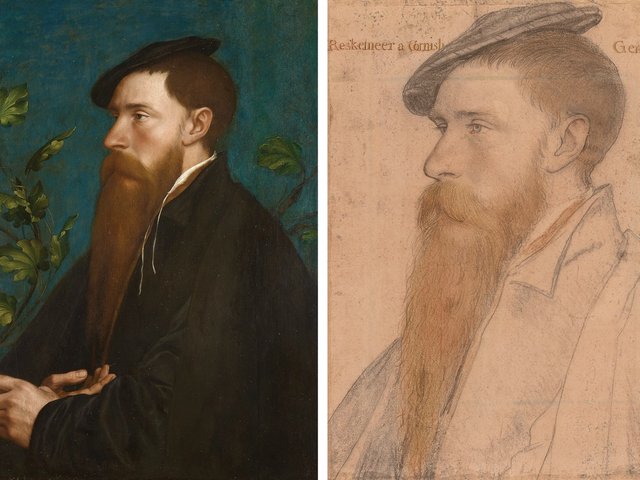

Goldring is the latest in a line of biographers and art historians who have attempted to excavate that past. In so doing, she has taken the term “biographer” literally. This 424-page tome is an examination of Holbein’s life (1497/8-1543), and though generously illustrated, the author declines to indulge her readers in too much pictorial interpretation. Neither Holbein’s visual conceits, nor his deployment of symbolism, are Goldring’s particular interest. She alludes only lightly to the innovative beats his works have made across the story of art: be that a near unmatched level of verisimilitude in his portraiture; an unprecedented degree of archaeological authenticity in his ground-breaking Dead Christ in the Tomb (1521-22, Kunstmuseum Basel); or an exploration of the science of perspective that, though most famously evident in the anamorphic skull in The Ambassadors (1533, National Gallery, London), is explored throughout his career.

Instead, Goldring’s focus, and great strength, is her scholastic ability to interrogate the documentary evidence that informs the production of Holbein’s work, using it to unpick the where and the when, and to correct or qualify assertions that have long gone unchallenged.

The book is structured chronologically, with each chapter subdivided into several key biographical moments. Within this user-friendly text-book approach, Goldring’s extensive, dedicated and often granular detective work throws up new theories, substantiates assumptions and contributes to the ongoing debate.

She comes into her own when dealing with the second half of Holbein’s career, while he was at the Tudor court of Henry VIII. For example, she has delved into the royal palace of Westminster’s inventories and discovered that the court chambers of the Duchy of Lancaster were adorned with green fabric. With this detail she can now suggest that the green curtain Holbein has included in the 1527 portrait of Sir Thomas More (Frick Collection, New York), may indicate that it was painted to celebrate the sitter’s newly acquired status as chancellor of that duchy.

Unearthing new evidence

Meanwhile Goldring goes to considerable lengths to prove the assumption held by many scholars that More would have had several copies made of the Frick portrait type. Her research has led her to another version, now located in Crosby Moran Hall in London, that “may have been executed during Holbein’s lifetime”. She moves on to gather evidence for single portraits taken from sketches of other sitters, which were likewise used for the lost painting of Thomas More and his Family (also dating to 1527). In addition, her re-examination of correspondence written in Latin between the More family and the Dutch humanist Erasmus, where the latter describes his joy at receiving the gift of a pittura (painting) by Holbein of its members, rather than a figura (the term that would normally relate to a drawing) prompts Goldring to suggest that the artist presented Erasmus with a smaller-scale (also lost) painting of the above-mentioned family portrait. With such close attention to the detail, she has perhaps answered a conundrum that has confounded other writers (including this one), who have too easily assumed that Holbein presented Erasmus with a drawing of the family, possibly the example now located in the Kunstmuseum Basel.

Goldring also dives into ongoing Holbein debates where documentary evidence is not forthcoming. In these instances, her conjecture remains intriguing, albeit not always more convincing than other theories in circulation. Her speculation that a miniature of an unknown lady—versions of which are in the British Royal Collection and Buccleuch Collection—may be Jane Seymour’s sister Elizabeth Seymour-Cromwell is a thoughtful addition to a list of suggested sitters that includes Anne of Cleves (this author’s proposal), and Katherine Howard.

On a stylistic note, Goldring’s academic caution is writ large, with the effect of undermining her evident authority. Her continual need to qualify so much of her thinking with “perhaps”, to preface it with “one cannot know”, or state that something is only “probably” the case, though of course true, nevertheless leads to a slightly unsettling reading experience over the duration of so many pages. This scholastic humility gives the cumulative effect that Goldring raises more questions than she answers. This is particularly frustrating given that she answers a great deal.

• Elizabeth Goldring, Holbein: Renaissance Master, Paul Mellon Centre, 424pp, 250 colour illustrations, £40 (hb), published 11 November 2025

• Franny Moyle is the author of The King’s Painter: The Life and Times of Hans Holbein and Mrs Kauffman & Madame Le Brun (2021 and 2025, both Head of Zeus)