Last summer, a scientist answered a question that many of us may have mused on: why are birds so colourful? In a study supported in part by our grant-making organisation, Schmidt Sciences, birds were found to have evolved to accentuate their brightly coloured feathers via a layer of white and black feathers underneath. As the study notes, this is exactly the technique used by painters for centuries. Science and art, without knowing it, came up with the exact same answer to the question of how to make colours bright.

People often regard art and science as polar opposites. Artists and scientists speak different languages and have wildly divergent skills on the spectrum from analytical to intuitive. If we peered at scans of their brain activity, different areas would flash on. And it is only the rare, gifted individual—think Leonardo da Vinci—who thrives in both domains.

But as both disciplines have faced severe US federal funding cuts—resulting in the closure of entire organisations, layoffs and the loss of talent to other fields or countries—it is particularly urgent for advocates in public and private sectors to recognise that art and science are connected ways of understanding the world. They each inspire the other, working best in concert, and supporters of one would do well to step up for the other.

The artist Constance Sartor working aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute's research vessel Falkor (too) as part of the Artist-at-Sea programme Courtesy the Schmidt Ocean Institute

I am not a scientist, but I work with them. I am also married to one. Scientists arrive at discoveries through testing, trial and error. They measure, calculate, form hypotheses and then start the cycle once more. Those of us with an artistic bent intuit. We channel emotions, use hunches, set out boldly and seek resonance in new ways of seeing and understanding.

These distinct styles are, in fact, different pathways to arrive at the same destination. As Leonardo was perfecting the Mona Lisa’s famously enigmatic smile, with one corner of the mouth curled just so, he was simultaneously studying human anatomy and musculature. This was a man pursuing truth, doggedly and intensively, by two different routes. Medieval-era Islamic artists demonstrated a deeply advanced understanding of geometry in their tilework. Alexander von Humboldt, the pioneering 19th-century naturalist, used drawings to demonstrate the variety of South American plant and animal life across latitudes and between elevations.

Constance Sartor, Seastar, 2021 Courtesy the artist

The challenge for modern cross-disciplinary efforts is the immense specialisation and advances in knowledge that have occurred since Leonardo’s time. For one person to be an artist and scientist is a challenge, and for artists and scientists to meet, and have opportunities to connect and collaborate, we need effort and funding. This is why our philanthropy crosses disciplines programmatically, seeking what happens at the edges and intersections.

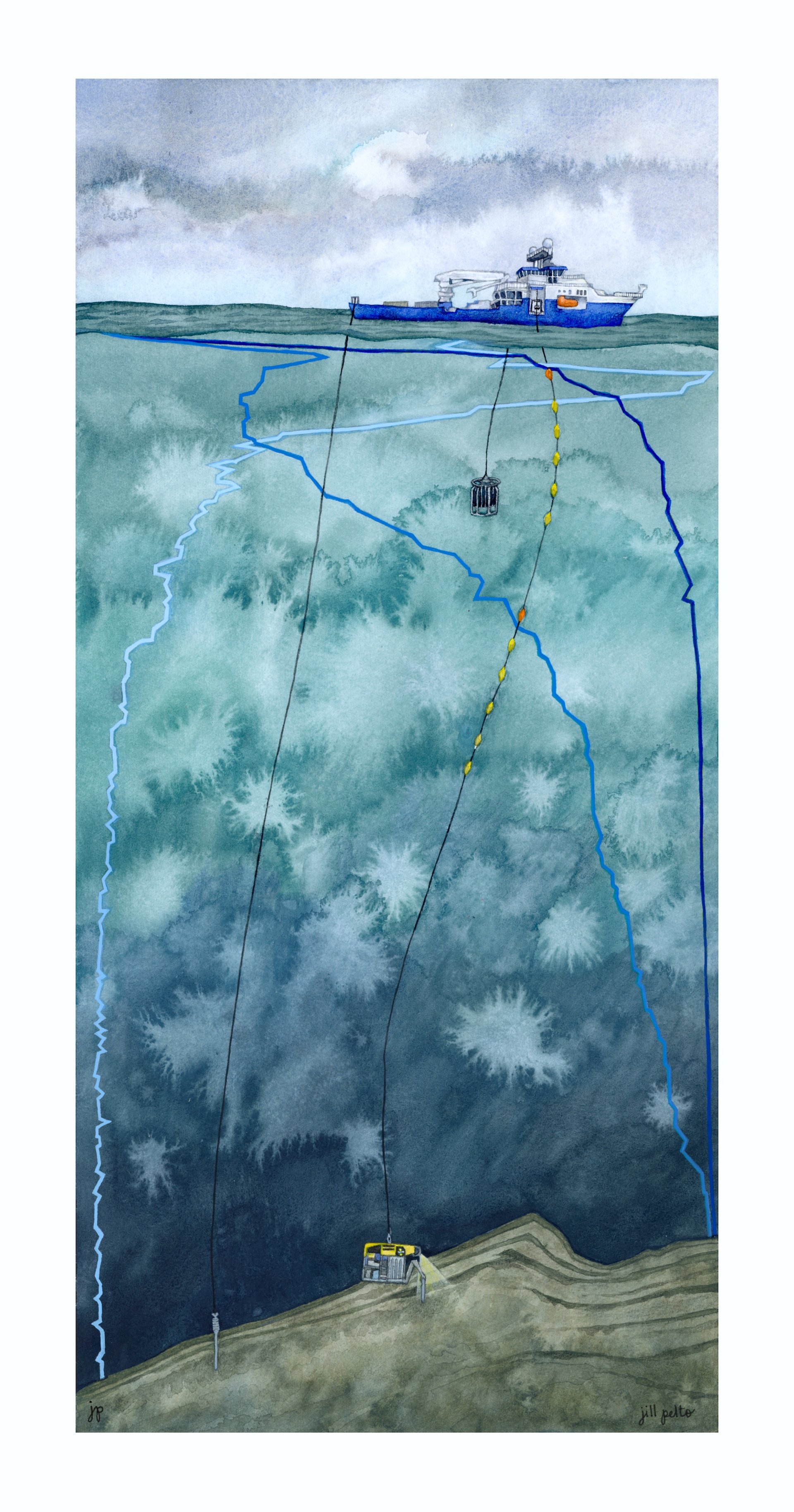

Just last year, in a collaboration that arose aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s research vessel Falkor (too), scientists worked with the artist Constance Sartor to illustrate their study on underwater mountains (inspired by Von Humboldt). Jill Pelto, like many artists raising alarms about climate change, advocates for the planet through her art. Sartor and Pelto are both part of Schmidt Ocean’s Artist-at-Sea programme, which has shared marine science with new audiences for the better part of a decade, helping everyone understand—whether they live on the coast or have never seen the sea—why a healthy ocean matters. It is also why we have extended our support of art and science to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, with the Eric and Wendy Schmidt Environment and Art Prize, and supported humanities scholars using artificial intelligence.

Poetic thinking

Jill Pelto, Beneath the Falkor (too), 2024 Courtesy the artist

When art and science come together, we find discovery and wonder. For example: you may imagine you are currently in one place as you read this. But in fact, we are all hurtling through the galaxy on a rollercoaster going 1.3 million miles per hour. The thumb you are scrolling with, just like every atom you contain, was once part of a star that exploded and travelled 400,000 light years to be where you are right now. This type of thinking, at once scientific and poetic, can help us grasp what makes our existence on this planet so extraordinary and our responsibility to protect it so urgent.

Both art and science rest upon a single, necessary foundation: freedom of thought. The freedom to imagine and to create is part of human nature and the underpinning of a free people. Undermining scientific inquiry also suppresses artistic expression, and vice versa.

The good news is that, in practice, it is hard to suppress imagination. Humans are curious and we like to talk to each other. We are also gifted with imagination—and the ability to act on it—and we will find a way to meet this moment, so that our curiosity, our discoveries and the soul-stirring language of art can continue to flourish.

- Wendy Schmidt is president and co-founder of the Schmidt Family Foundation and Schmidt Ocean Institute, and co-founder of Schmidt Sciences