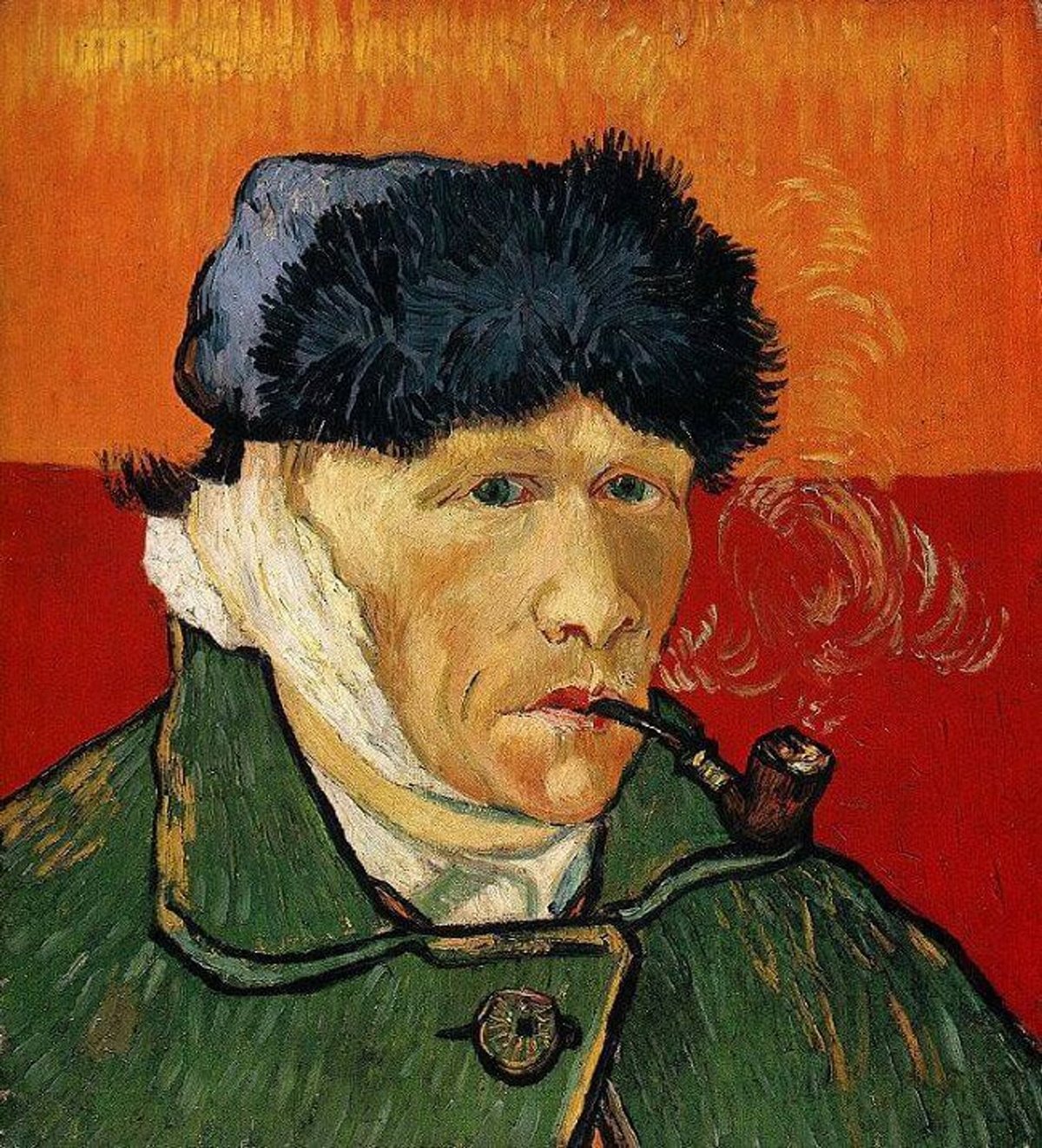

In mid-January 1889, three weeks after mutilating his ear, Van Gogh painted two astonishing self-portraits, depicting himself with a prominent bandage, covering his mutilated ear. The famous one is in London’s Courtauld Gallery (below left).

The other, in a private collection (below right), has only occasionally been displayed at the Kunsthaus Zurich. The last time it was lent to an exhibition outside Switzerland was in 1990. This blog post focuses mainly on this second, lesser-known painting, Self-portrait with bandaged Ear and Pipe, which has an orange-red background and in which the artist is smoking.

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait with bandaged Ear (Courtauld Gallery, London) and Self-portrait with bandaged Ear and Pipe (private collection, both January 1889)

Van Gogh cut off most of one of his ears in Arles on the evening of 23 December 1888, after a row with his housemate, Paul Gauguin. Although the wound was very serious, Van Gogh appeared to make a rapid recovery and was released from hospital on 7 January 1889.

Vincent quickly got back to painting, writing to his brother Theo ten days later: “I’ve started work again and I already have 3 studies done in the studio”. Two of the paintings were the pair of self-portraits, along with a still life. All are fine works, evidence that the artist had lost none of his skills.

The most striking compositional element of Self-portrait with bandaged Ear and Pipe is the powerful background—orange and red. The division of the colours is level with the artist’s eyes, giving an added emphasis to his direct gaze. With the artist's coat in green, the complementary colour to red, the picture sings out.

Another distinguishing feature in the self-portrait is the artist’s beloved pipe, which he felt helped him relax. The swirling smoke enlivens the vibrant picture. Three months after completing the painting Vincent wittily quoted Charles Dickens in a letter to his sister Wil: "Every day I take the remedy that the incomparable Dickens prescribes against suicide. It consists of a glass of wine, a piece of bread and cheese and a pipe of tobacco.”

Van Gogh is clean-shaven (or almost so), although in nearly all of his 34 other painted self-portraits he sports a beard and moustache. Presumably he had been shaved when he was treated in hospital and his facial hair had not yet grown back.

Both self-portraits were done within a day or two of each other. The fact that the artist’s beard and moustache seem slightly shorter in the privately owned one suggests that it may have been done just before the one in the Courtauld.

It is startling that Van Gogh decided to paint two self-portraits when he was in such a physically vulnerable state. He needn’t have painted self-portraits and could have done still lifes. If he wanted to do self-portraits, he could have easily depicted his head from the other side, turned away from the mutilated ear. Instead, he deliberately positioned himself to display his very prominent bandage. The two self-portraits clearly make a statement.

Depicting the bandage may have been Van Gogh’s brave attempt to come to terms with what had occurred—acknowledging his injury. He found it very difficult to write about the self-mutilation in his letters, but perhaps he could attempt to deal with it through his art.

But what would those around him have thought about the two self-portraits? In Arles, the paintings would probably have been seen by his closest companion, the postman Joseph Roulin, and the artist’s doctor friend, Félix Rey. Disturbing as they were, the two works represented powerful evidence to convince them that Van Gogh had lost none of his artistic creativity. At the time he may have wanted to express his determination to overcome the traumatic experience.

One of the self-portraits, the Courtauld one, was probably sent in a consignment of paintings to Theo in May 1889. One can only imagine how Theo must have felt when he opened the crate, to see such an explicit depiction of his injured brother. Sending this picture to his brother in Paris may also have partly represented a cry for help.

By the spring, Van Gogh’s problems had become fully apparent. After his brief recovery in mid-January 1889, his mental condition deteriorated and he was readmitted to hospital at the end of that month. He was then in and out of hospital for the next few months and in May he felt he had no alternative but to enter the mental asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. He stayed there for a year, before moving to Auvers-sur-Oise, where he died from suicide on 29 July 1890.

The first illustration

Three years after Van Gogh’s death, Self-portrait with bandaged Ear and Pipe was chosen to represent the artist in an exhibition with an ambitious title: Les Portraits du Prochain siècle (Portraits of the Next Century). This presentation of portraits of avant-garde artists and writers was held in Paris at the gallery Le Barc de Boutteville in July 1893.

It was an honour for Van Gogh to be included, since he was not yet well known. Even more surprising was the choice of painting to represent him, since many exhibition-goers would not have known of the ear mutilation and the purpose of the bandage (and of those who did know, some might have found the picture disturbing).

The exhibition received scant press attention, but it was described in a lengthy article in the Revue Encyclopédique. The writer, poet Paul-Napoléon Roinard, expressed his surprise on seeing the Van Gogh self-portrait: “Oh! The beautiful and wild harmony of this primitive barbarism of art: the juxtaposition of colours.” Roinard was presumably referring to the orange-red background.

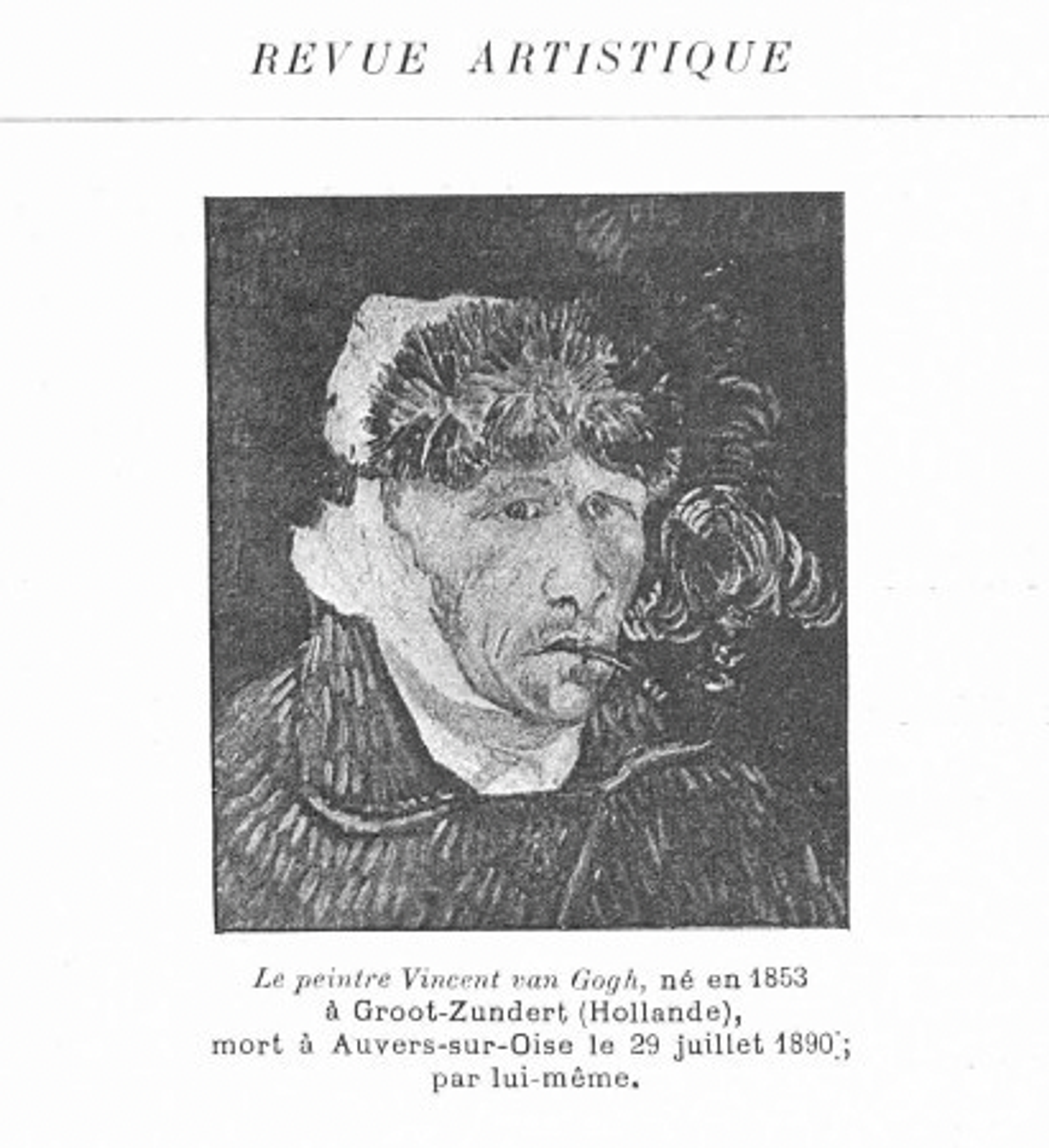

Reproduction of Van Gogh’s Self-portrait with bandaged Ear and Pipe

Revue Encyclopédique (15 November 1893)

This review also included a photograph of the self-portrait. It was the first time that an image of one of Van Gogh’s paintings had been reproduced in the press, an early sign of his imminent fame.

The early black-and-white photograph offers an unusual opportunity to see how the condition of the painting may have changed. In 1893 the light streaks on the coat seem to have been more pronounced, the back of the hat appears lighter and the billowing smoke has greater emphasis. The division of the orange-red background is imperceptible in the black-and-white reproduction. However, some of these differences may have been due to the limitations of early photography.

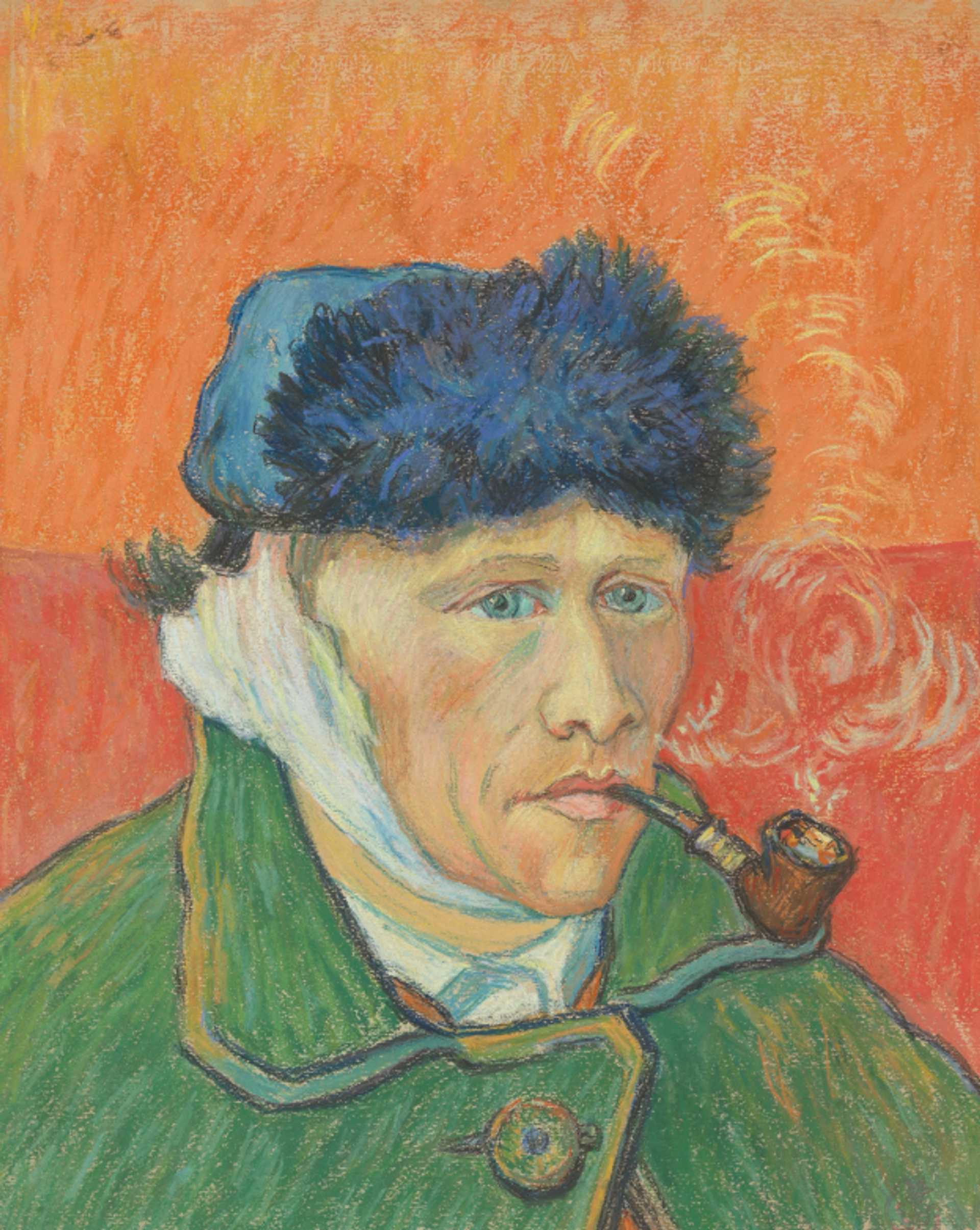

By 1893 the painting had been acquired by the artist Emile Schuffenecker, a very keen collector of Van Gogh’s work. Schuffenecker once drew a coloured copy of the self-portrait, evidence of his admiration for his fellow painter. Acquired by the Van Gogh Museum in 1974, the copy has only been displayed once, in 2016, and is little known.

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait with bandaged Ear and Pipe: the 1893 photograph and the painting today

Emile Schuffenecker’s chalk copy (1892-1900) of Van Gogh’s Self-portrait with bandaged Ear and Pipe

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Looted by the Nazis

By the 1930s Self-portrait with bandaged Ear and Pipe was owned by the Paris dealer Paul Rosenberg, who was of Jewish origins. After the German occupation of France in 1940 the painting was hidden in a bank vault in Libourne, near Bordeaux, for safekeeping.

The self-portrait was seized the following year by a Nazi task force and moved to Paris, where it was acquired by Hermann Göring, Hitler’s deputy. In 1942 the painting was sent to a Swiss lawyer acting on behalf of Göring’s interests.

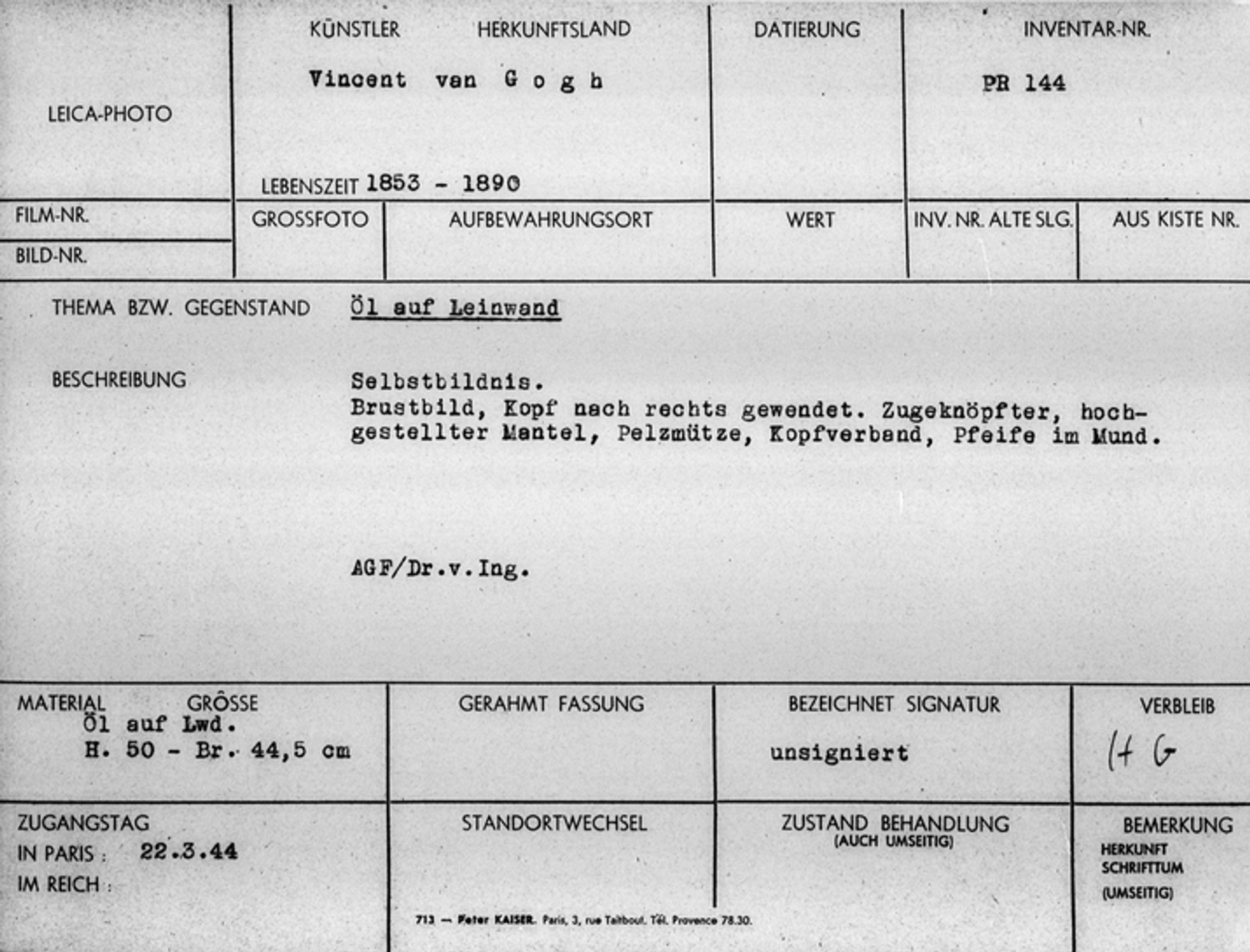

German card recording the arrival of the looted Van Gogh self-portrait in the Jeu de Paume depot, Paris, 22 March 1944

Database of Art Objects at the Jeu de Paume

Declassified UK government papers record that the Van Gogh was subsequently “smuggled into Switzerland by diplomatic bag”, by the German authorities. The self-portrait was recovered in Zurich in 1945 and three years later it was restituted to Rosenberg. It is therefore not subject to any potential restitution claims.

In 1949 the self-portrait was bought by the Chicago steel-company owner and collector Leigh Block and his wife Mary. They hung it above the fireplace in the lounge of their luxurious apartment.

Block sold the Van Gogh in the early 1970s and it went to the Greek shipping tycoon Stavros Niarchos, who lived partly in Switzerland. Martin Summers, the London dealer who helped arrange the sale, recalled a meal with Niarchos at which the painting was offered at “a stiff price”, between $2m and $3m. Summer added that Niarchos “never discussed the painting at lunch, but on leaving casually said: ‘I’ll take it.’”

Niarchos is said to have had the Van Gogh flown by helicopter to his chalet in St Moritz for his regular winter visits. He died in 1996. The painting is now usually described as in an unnamed private collection, but it is most likely still with the heirs of Niarchos.

There are only four Van Gogh self-portraits still in private hands and theirs is by far the most important. If the painting comes onto the market, it would almost certainly fetch a record price for a Van Gogh, beating Orchard with Cypresses (April 1888), which sold for $117m in 2022. The Niarchos family ended up with a bargain.