The Lee Miller Archives, which were established after the American photographer’s vast collection of photographs and writings were discovered in the attic of her Sussex home following her death in 1977, is raising money to provide urgent conservation of thousands of her negatives, some of which are nearly 100 years old.

Proceeds from the sales of works on show at Lyndsey Ingram gallery in London will ensure that as many as 60,000 negatives and prints—some of them in a perilous state—will be frozen and preserved. Miller’s archive is stored at Farleys House in East Sussex where she lived with her husband, the art historian and Institute of Contemporary Arts co-founder Roland Penrose, from 1949 until her death.

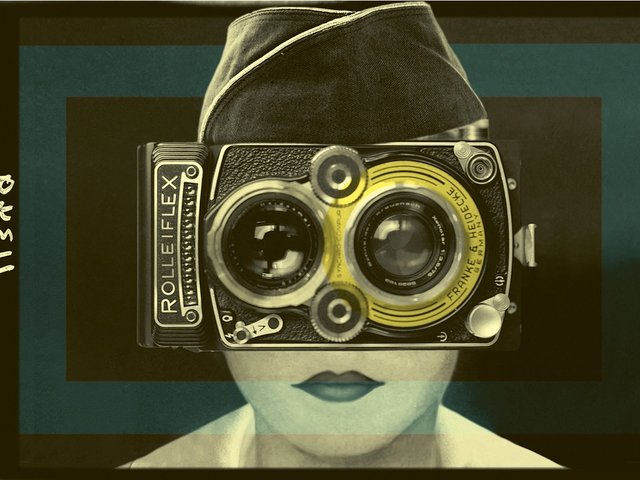

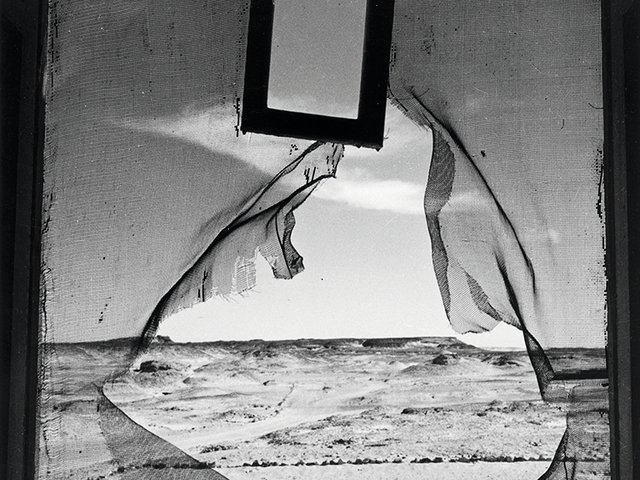

The exhibition, Lee Miller: Performance of a Lifetime (23 January-25 February), examines the pivotal role of theatre, staging and performance throughout Miller’s practice—from her arrival in Paris in 1929 and her involvement with the Surrealists to the final years of the Second World War, during which time Miller worked as a photojournalist. Prices start at £3,800; several corresponding prints are also currently on show at Tate Britain as part of a survey show.

Ami Bouhassane, Miller’s granddaughter who runs the Grade II-listed Farleys House together with her father Antony Penrose, tells The Art Newspaper how Miller’s trove was discovered in the attic by chance almost 50 years ago. “Just after I was born, my mum was looking for pictures of my dad as a baby and she went up into the attic, but instead of coming back down with baby pictures she found the contact sheets and manuscripts from the Siege of Saint-Malo.” It was the first combat battle that Miller covered as one of the first female war correspondents, covering the conflict for Vogue and Life magazines.

It’s only in the last 12 years that she has got shows in her own right, and the fact that she’s a woman is not such an issueAmi Bouhassane, Miller’s granddaughter

“She never talked about her career,” Bouhassane says. “My dad had no idea. He knew that she’d been a photographer, that she could take good pictures and that she’d been a model, but he had no idea at what level, and he had absolutely no idea about what she’d done during the war.” The moment Miller’s work was discovered, Penrose resolved to establish her archive.

Miller’s frontline war experiences, including witnessing the liberation of the Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps, and her subsequent post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) when she returned home are well documented. “After the war, Lee really struggled to come back and be a fashion photographer, to get excited about hats and handbags after everything she’d seen,” Bouhassane explains. “She had PTSD and she suffered from post-natal depression. But the attitude was to ‘put up and shut up’. She drank for a bit because that was the only accepted way of dealing with it.”

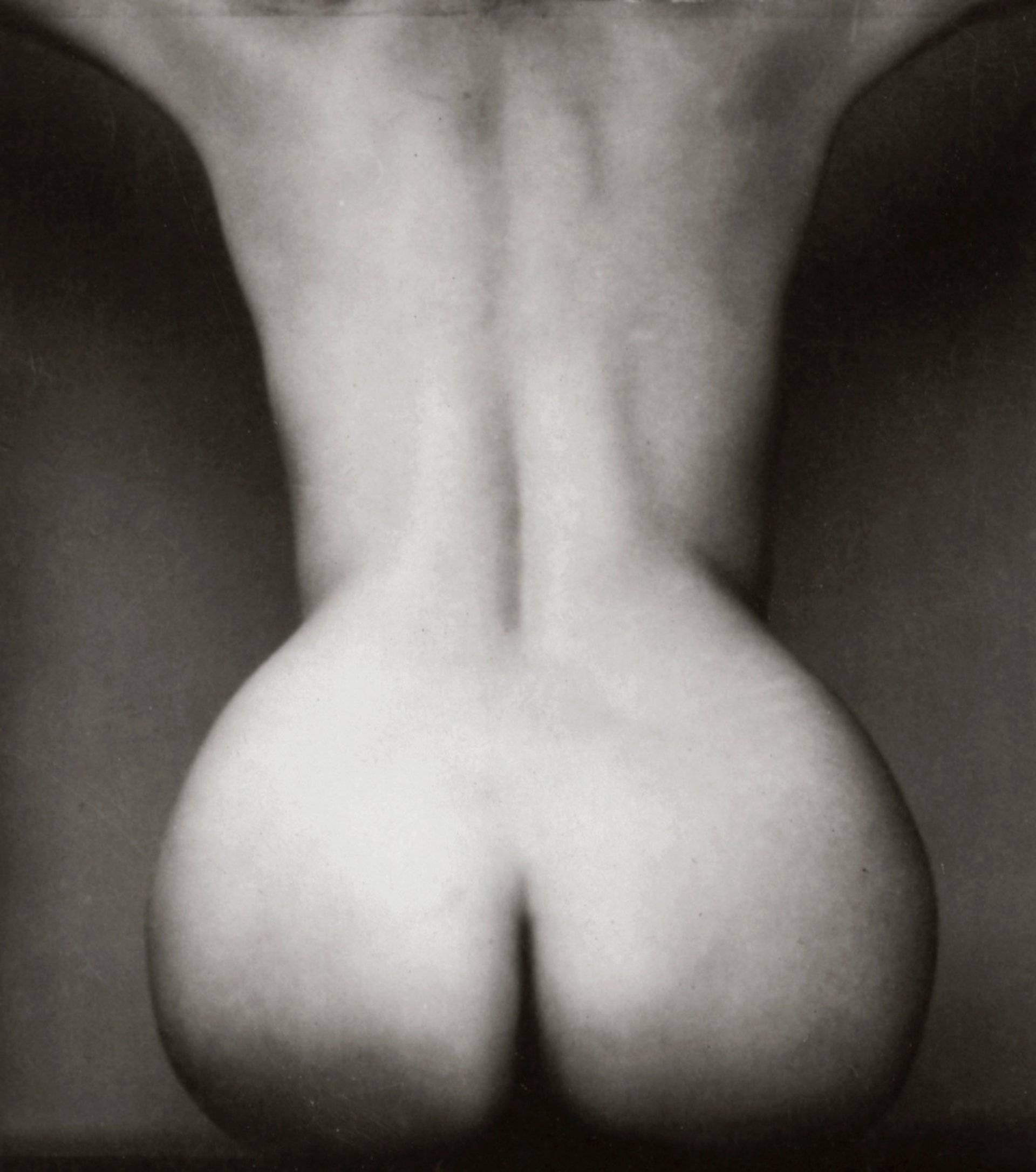

Lee Miller, Untitled Nude back (thought to be Noma Rathner), Paris (1930) © leemiller.co.uk

Working as a photojournalist after the war also proved difficult, so when Miller and Penrose moved from London to Farleys in 1949 she boxed up all her negatives and prints, never to unpack them. Despite this, Bouhassane thinks a part of Miller remained attached to her work. “It would have been a hell of a lot easier to make a massive bonfire and burn it all,” she says. “So even though Lee turned her back on photojournalism and art photography, on some level she felt that she didn’t want to part with it and that’s why she left it in the attic.”

Bouhassane recalls how, when she started working for the archive 26 years ago, Miller’s work was “valued at pennies”, and she and her father had to fight to get recognition for the photographer. “I used to pitch shows with my dad, and we’d have to play this game where you’re trying to appeal to somebody to give you a Lee Miller exhibition, so you just name drop all the 20th-century male artists she’d photographed or had affairs with, and then we’d get a show. It’s only in the last 12 years that she has got shows in her own right, and the fact that she’s a woman is not such an issue.”

The archive is now working with the Preus Museum in Norway, which specialises in photography and preserves their negatives by freezing them. “It’s really the only way that you can stop them from degrading completely,” Bouhassane says. “Luckily, you can do it in a domestic freezer, but it’s now a matter of finding space for all the freezers we will need.”

First, there are plans to digitise the archive, though the process will be determined by how much funding the organisation can raise. The Lee Miller Archives is represented in Europe by CLAIR gallery in Switzerland and works on a case-by-case basis with other galleries. The collaboration with Ingram came via the curator Clara Zevi, the founder and director of Artists Support, an initiative that helps artists and estates raise money.

As Zevi points out, the long-term goal is to turn Farleys House from a business into a charity to secure Miller’s legacy. “It’s such a special place; it’s not your regular house museum because you really feel that it was lived in and that a lot of fun was had there, too. Ami and her father have done such a beautiful job conserving both the work and the story in that house.”

Bouhassane acknowledges relinquishing control of the archive “will be a big thing”. But, she adds, “we have done a lot of soul searching and feel this is the best way to be able to make sure that Farleys remains accessible. We’re always trying to look towards Lee’s legacy. It was so hard to get her recognised, it would be a shame if there was nothing left for future generations.”