This year’s Singapore Art Week (SAW) includes several celebrations of Southeast Asia’s female artists, including the release of the book You Are Seen: Women’s Contemporary Art Practice in Southeast Asia, and the exhibition Fear No Power: Women Imagining Otherwise of five trailblazing artists from the region at the National Gallery Singapore (NGS). “It’s going to be a big women’s moment!” says Audrey Yeo, the president of the Art Galleries Association Singapore (AGAS) and founder of the Singapore gallery Yeo Workshop, which published You Are Seen and will show Indonesia’s Citra Sasmita at its Gillman Barracks space and at Art SG.

The projects reflect decades of ongoing efforts to give women artists their full due, and belie a complicated terrain for them around the diverse region. “It is hard to generalise what the current situation is for women artists in Southeast Asia,” says Krystina Lyon, a collector and the author of You Are Seen. “Countries with less institutional support or where censorship and conservative social norms persist tend to be more challenging for women artists. It also depends on the individual art practice and how provocative it is to the conservative and patriarchal home contexts.”

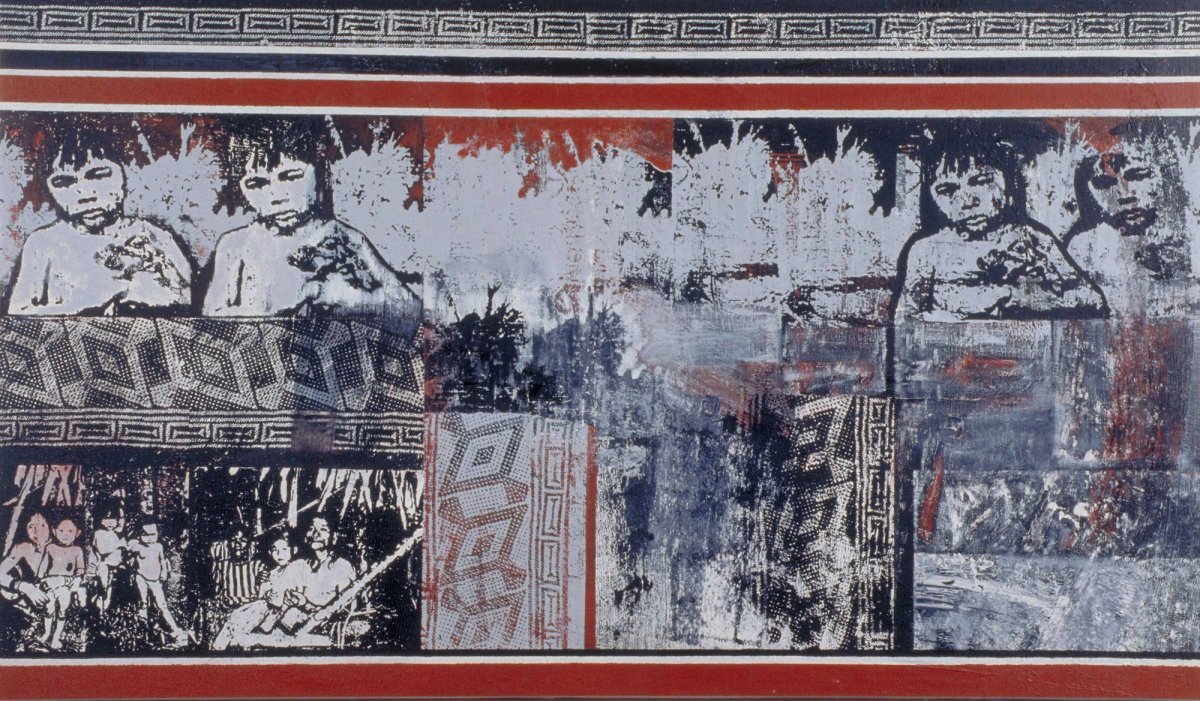

Imelda Cajipe-Endaya’s Buhay ay Vodavil Komiks (Life is a Vaudeville Comic Book) from 1981

© the artist; courtesy National Gallery Singapore

Conversations about gender and feminism are much more evident now than a decade ago

Lyon cites how the Filipina performance artist Eisa Jocson “has been more widely recognised internationally because of the subversiveness of her work, yet the Philippines has a wonderfully established art scene that includes many acknowledged women artists like Imelda Cajipe-Endaya, Julie Lluch, Nicole Coson, Jill Paz and Pacita Abad, to name a few.” Artists working in performance, like Singapore’s Suzann Victor and Indonesia’s Arahmaiani, faced extra barriers due to former prohibitions on that medium. “Chuu Wai from Myanmar now lives in exile due to clashes with the military regime. Citra Sasmita, who is now well established internationally—with a solo show at London’s Barbican last year—has also experienced tensions from the local market in Bali due to her resistance to deeply entrenched restrictions [favouring tourism over Indigenous rights],” Lyon says.

The NGS exhibition Fear No Power (until 15 November) features Malaysia’s Nirmala Dutt, the aforementioned Imelda Cajipe-Endaya, Indonesia’s Dolorosa Sinaga, Thailand’s Phaptawan Suwannakudt and Singapore’s 2026 Venice Biennale Pavilion artist Amanda Heng. The NGS’s chief curator Patrick Flores, says it “allows us to situate Singapore’s own socially responsive and gender-sensitive practices within a wider Southeast Asian context. By placing Amanda Heng’s work alongside the other Southeast Asian artists in Fear No Power, we see how Singaporean concerns, from gendered labour to the politics of public space, resonate with regional histories of activism, post-authoritarian transition, and everyday resistance.” The exhibition furthermore, “sheds light on how Singapore’s artistic transformations were never isolated or existed in a vacuum. Many of the questions these artists are grappling with—modernisation, nation-building, community and care—were shared across Southeast Asia.”

The Singapore Art Museum (SAM) regularly spotlights the region’s female artists, such as last year’s solo show of the Malaysian multidisciplinary artist Yee I-lann, while Womanifesto and the Filipina collective Kasibulan have provided platforms for raising the profile of Southeast Asian women artists. Hong Kong’s non-profit Asia Art Archive has also undertaken extensive programming and research on regional women’s topics

In the market, Yeo says, the Southeast Asia landscape “mirrors much of the world: there are simply fewer women artists than men, and the disparities echo across pricing, visibility, and opportunities. The reasons are rarely singular. They sit within layers of cultural expectation—traditional gender roles, family obligations, and the quiet, inherited scripts about ambition that shape who feels permitted to take up space in the art world.”

Dolorosa Sinaga’s bronze Solidarity (2000/25)

© the artist

Lyon says she decided to write You Are Seen because she observed two gaps: “A lack of accessible narratives that centre Southeast Asian women and gender diverse artists within both regional and international art histories; and a shortage of practical, artist-centred documentation that could be used by curators, students and collectors”. The project grew from her work as a collector and researcher, wanting to document how the 35 artists featured in the book “sustained and advanced” their practices, to raise awareness of them, to provide a resource for researchers and curators, and to advocate for “more equitable institutional and market recognition”.

“Conversations about gender and feminism are much more evident now than a decade ago—in academic conferences, in biennales, and in the programming of major museums,” Lyon says. She anticipates that coming years will see three parallel trends: more archival projects that centre women artists and raise their global prominence; that the ongoing efforts of artist-run and feminist platforms will reshape the larger establishment; and that the gallery-level market will continue to improve. “However, major retrospectives [and] canonical histories under institutional remits will always lag behind unless stakeholders commit to long-term programmatic change,” she says. “Visibility is improving but for lasting traction there will need to be more investment in curatorial fellowships, acquisition policies, teaching curricula and research funding.”

- Fear No Power: Women Imagining Otherwise, National Gallery Singapore, 9 January-15 November 2026