In a colonial-era building in Singapore, a video of the world’s tallest indoor waterfall at Jewel Changi Airport is projected onto white curtains concealing a dark room. Inside, viewers sit on a floor mattress which feels like a fragile raft, surrounded by visceral footage of Thailand’s Vajiralongkorn Dam.

The work, Drifting Bodies (2025) by the architectural duo field-0, encapsulates the theme of the eighth edition of the Singapore Biennale, called Pure Intention. “The idea is that intention is not the whole story,” says Selene Yap, a co-curator of the Biennale. “Systems can generate a certain kind of afterlife, and there are side effects.” While the waterfall impresses, it also has consequences, she adds. The work uncovers how Singapore imports hydropower through transnational infrastructure, including the Vajiralongkorn Dam, whose construction has displaced Thailand’s indigenous Karen hill tribe, forcing many to live in floating homes on the reservoir.

Just as viewers move beyond the spectacle of the waterfall—a symbol of Singapore’s polished efficiency—the Biennale exposes the hidden personal narratives behind various systems, exploring what the curators describe as “the incidental and peripheral”.

“[In Singapore] we tend to promise some form of clarity, coherence and orderly progression. But the works assembled for the Biennale offer a preview into something that is more uncongealed or incoherent,” says Yap, who collaborated with curators Hsu Fang-Tze, Ong Puay Khim and Duncan Bass.

Founded in 2006, the Biennale is organised by the Singapore Art Museum (SAM) and commissioned by the country’s National Arts Council. While previous editions of the event have concentrated works in SAM, this year more than 100 works are spread across five neighbourhoods.

The Biennale is billed as a signature event of SG60, Singapore’s citywide 60th anniversary celebration. “It didn’t occur to us as a nation-building project,” Yap says, though ideas of place-making and civic identity linger subtly in the background. Yap stresses the significance of engaging with venues across the city, and the chief curator at SAM, Shabbir Hussain Mustafa, similarly describes Singapore itself as a “collaborator” of the event.

Works are embedded in a diverse range of sites, from vernacular spaces such as shopping malls, to early public housing at Tanglin Halt and former colonial grounds, such as Fort Canning Park.

Deliberately open ended, the amorphous title Pure Intention embraces a litany of themes which ripple throughout the show, including invisible systems of control, resistance, ecology, war and colonialism. The cluster of video works (including Drifting Bodies) in the Wessex Estate—a former colonial residential enclave for British military families—is perhaps the strongest. While there is little connective tissue between works at other sites, here the underlying maritime themes and stories of island communities navigating displacement and erasure unite the pieces.

On the ground floor, the Puerto Rican artists Allora & Calzadilla’s Under Discussion (2004) shows a fisherman’s son sitting on an upturned conference table turned motorboat, navigating a historic fishing route around Vieques, a Caribbean island once used by the US Navy as a weapons-testing range. Through an absurdist approach, the artists explore the idea of individual agency amid loss of sovereignty.

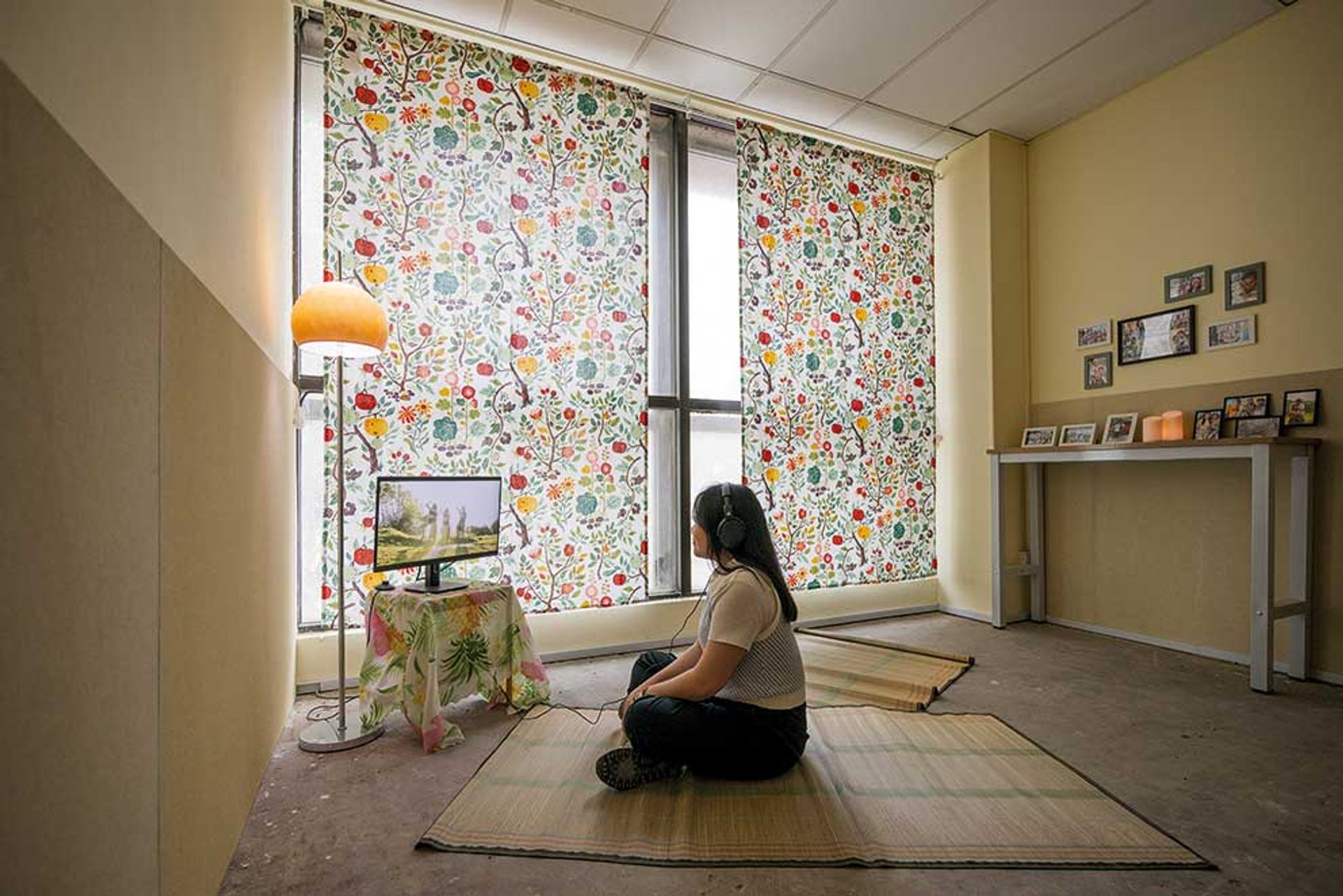

The Filipino Superwoman X H.O.M.E. Karaoke Living Room by Eisa Jocson is a makeshift karaoke lounge that puts the spotlight on the often difficult lives of Filipino domestic workers

Courtesy Singapore Art Museum

Upstairs, in a video, Seaweed Story (2022), a choir of elderly haenyeo women—Korean free divers known for reaching the ocean floor to collect edible seaweed—sing a solemn ballad. The work by the visual research group ikkibawiKrrr reflects the resilience of an aging community whose traditions are disappearing. The artists, who spent nearly two years on Jeju Island with haenyeo women, also worked with them to make playful seaweed wall reliefs.

This community-engaged approach extends beyond the works in Wessex Estate. The Filipina artist Eisa Jocson, for instance, worked with the migrant worker rights group Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME) to hold workshops for Filipino foreign domestic workers (known colloquially as “helpers”). They chose personal anthems celebrating their dignity, and Jocson helped them to create accompanying music videos. What resulted is The Filipino Superwoman X H.O.M.E. Karaoke Living Room (2025), a makeshift karaoke lounge screening the videos in a shop unit in Lucky Plaza mall—a gathering place for Filipino foreign domestic workers. Although the wall text mentions these workers’ “displacement and sacrifice”, it treads carefully and is not overly critical, even though migrant workers often face marginalisation and mistreatment.

The Biennale’s strength therefore lies not in confronting socio-political issues, but in moments like Jocson’s work, which spark dialogue with local sites. The works at Raffles Girls’ School is another example—Bandung-based Japanese artist Kei Imazu’s monumental paintings explore the deception and violence of Japan’s occupation of Indonesia. They are particularly resonant given that the the school’s former campus was the headquarters of the Kempeitai, the Japanese military police, during war years.

In contrast, the institutional venues, such as the National Gallery Singapore and SAM’s industrial space in Tanjong Pagar Distripark, lack potency and impact. SAM’s ground floor is stuffed with so many disparate works that it dilutes the viewing experience. This was a similar case with the exhibition’s 2022 edition, confoundingly titled Natasha, which filled two floors of SAM with largely underwhelming works.

As the Biennale continues to find its footing, it is worth noting that the country’s contemporary art scene is still young. “The Biennale is often described as a global format, but in Singapore, we recognise that it plays a very local role,” Yap says. Given this context, placing art beside spice market vendors, hair parlours, Chinese medicine shops and a café serving nasi lemak (a popular Malay rice dish) makes sense. Instead of boldly challenging the status quo, this is a quiet Biennale that shares deeply personal stories and pays homage to conversations and rhythms that already exist.

• Singapore Biennale: Pure Intention, until 29 March, various locations, Singapore