Think of Alberto Giacometti and most of us will first conjure the Parisian avant-garde and existential angst. But there was another side to Giacometti, one rooted in his birthplace, the remote Swiss Alpine village of Stampa. Initially eager to escape the shadow of his father, Giovanni, who was also an artist, Giacometti followed that well-trodden path of youth, escaping the provinces for the glittering metropolis of Paris in 1922.

But, from the 1950s onwards Giacometti returned more and more often to the Swiss valley, starting to work in his father’s studio which had once felt stultifying.

“He didn’t want to be seen as the son of a Swiss painter or a boy from the Alps, but as a Parisian artist at the centre of the international avant-garde… And yet, the pull of Stampa and of the Engadine endured,” writes the curator Tobia Bezzola in his introduction to the exhibition, Alberto Giacometti: Faces and Landscapes of Home at Hauser & Wirth in St Moritz.

A Giacometti self-portrait from 1920 © Succession Alberto Giacometti/2025, ProLitteris Zurich

The works he produced in the Alps were quite distinct from those made in Paris and, later, Geneva, portraying his mother, wife, villagers and the local landscape. “These were not exercises in nostalgia but distillations of his subject’s presence: mountains and faces were reduced to their essence, suspended between fragility and endurance,” Bezzola writes.

Family portraits

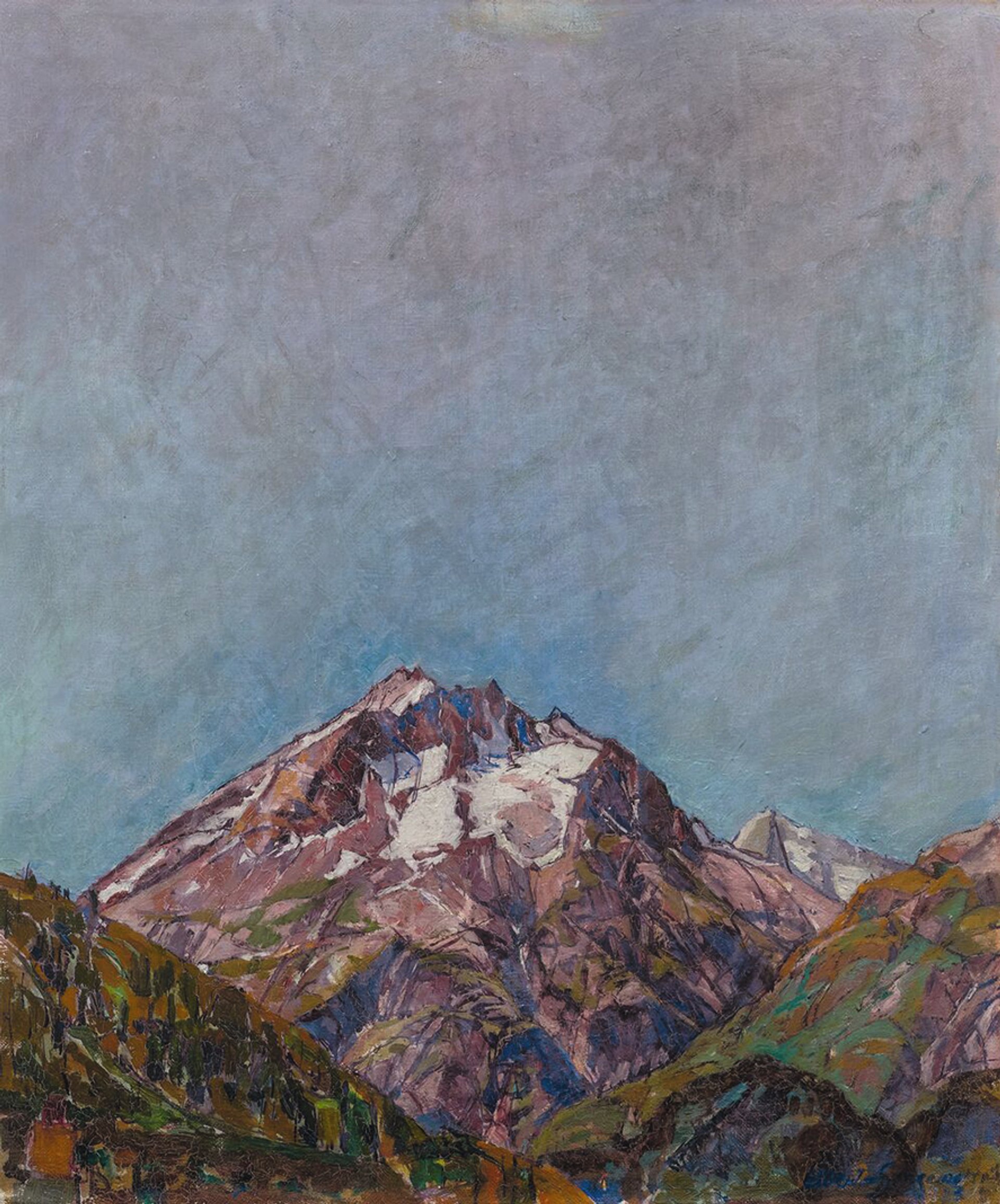

Such works, around 20 paintings, sculptures and drawings portraying his family and the landscape of Stampa and Maloja in the Bregaglia Valley, are the focus of the Hauser & Wirth show, in the luxury Swiss ski resort. The earliest works in the show date back to 1918 and through the 1920s, including sketches of Giacometti’s parents made when he was only 17, a self-portrait from 1920 and a painting of the local mountain, Monte del Forno, from 1923. Alongside these are later works from the 1930s and 50s.

Home was a place Giacometti tried to escape but, ultimately, could never abandon

The notion of departure and return, of the relationship between his life in Paris and “the rootedness of home,” as Bezzola puts it, is central to the exhibition. “The landscapes and the people of his childhood are not merely a background; they informed how he saw the world and are the core of his artistic vision,” Bezzola writes. “Home was a place he tried to escape but, ultimately, could never abandon.”

During the early 1950s, Giacometti kept a divide between his Parisian circle (who were not invited to visit Stampa or Majola) and the Alps (his mother never visited Paris), “as if there had been a tacit agreement that this place was sacred, an inviolate retreat whose intimacy had to be preserved,” Bezzola writes. But from the 1960s, as he started to visit his ailing mother more frequently, we see more of a connection between his two worlds.

Giacometti’s Monte del Forno (1923) © Succession Alberto Giacometti/2025, ProLitteris Zurich

The Hauser & Wirth exhibition, which includes loans from private and institutional collections as well as works for sale, concentrates on Giacometti’s output from the region. “We do not pretend to show also the other side, which would be Paris, Surrealism, Existentialism, his sexuality, his complicated relationships with women, which, frankly, are things that he would not talk about with his mother,” Bezzola tells The Art Newspaper. Nor would he have had the same conversation with farmers and villagers in the local bars of Stampa as he would have in the cafés of Paris. “In Stampa, he goes back and he’s always 18 years old—we gain a kind of innocence, and the work is landscapes, portraits of familiar people and interiors of the family home,” Bezzola says.

Audiences local and global

The St Moritz-distinct audience similarly informed Bezzola’s approach to curating the show. “On one hand, I was thinking of the local public, who may not have travelled to the major shows in New York, London or Paris. And then, of course, it’s international tourists, people from Latin America, all over Europe, from the US, from the Gulf states. So, it was important to shape a small, well-rounded exhibition.”

The exhibition also includes images by Ernst Scheidegger, the Swiss photographer who for decades was the only person to be allowed to photograph Giacometti in his very private Maloja studio and family home in Stampa. They met in 1943 when a young Scheidegger was doing his military service in the Alps. On seeing him drawing in his spare time, some villagers suggested he knock on Giacometti’s studio door, Bezzola says. “The Scheidegger photos are really the only ones that give us visual access to that side of his world,” Bezzola tells The Art Newspaper. “Any photographer travelling through Paris would knock on Giacometti’s studio, it kind of became mandatory. So, we have dozens of important photographers who visited him and did portraits [in Paris], but only Scheidegger had this exclusive access [to Stampa] thanks to their friendship.”

• Alberto Giacometti: Faces and Landscapes of Home, Hauser & Wirth St Moritz, until 28 March