In 2021, Art UK published a survey of London’s 1,500 public monuments, which found that for every sculpture of a named woman, there were two sculptures of animals. As the journalist Juliet Rix pointed out at the time, that did not mean the female body was not present on the capital’s streets. On the contrary: “There’s an extraordinary number of bare breasts on our public buildings,” she said, “from the Foreign Office to the Supreme Court.”

This art historical contradiction—this tension between overexposure and invisibility—is explored by Amy Dempsey in The Female Body in Art. She was not the only one to see it as a golden opportunity. When Dempsey asked the Australian artist Julie Rrap about featuring her work in the book, it was a firm yes. “I’m so pleased to be included,” Rrap replied. “It’s a book I have wanted to find for years.”

Dempsey is an independent scholar with a track record of wrestling gigantic themes (all the styles, schools and movements in Modern art, say) into something the general public wants to read. Most introductions to art history will start with the Venus of Willendorf, she says. But that meant covering 32,000 years in 80 works, a frankly bonkers task.

Instead, she opens with the Renaissance: Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (the goddess of love), Raphael’s Madonna della Sedia (the mother) and Hans Baldung’s The Witches (the hag)—as Dempsey puts it, “the good, the bad and the ugly of our history”. This is followed by a quick run through of the subsequent periods, before digging into the 20th and 21st centuries, which she thought readers would find most interesting.

Which artists and works she added to the mix was driven more by celebration than reproof. Wide-eyed warriors like Barbara Kruger and the Guerrilla Girls are present, with Dempsey highlighting their indelible and ever relevant quotes, such as the latter asking in 1989 whether women have to be naked to get into New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Such punchy pieces sit beside a raft of unexpected choices, and a lot of uncommon beauty. Not all the artists are women: an entry on Yves Klein’s Anthropometries becomes an exercise in, as Dempsey puts it, “taking off your 21st century lens” and understanding how positively the women he worked with, as human paintbrushes, responded to being involved.

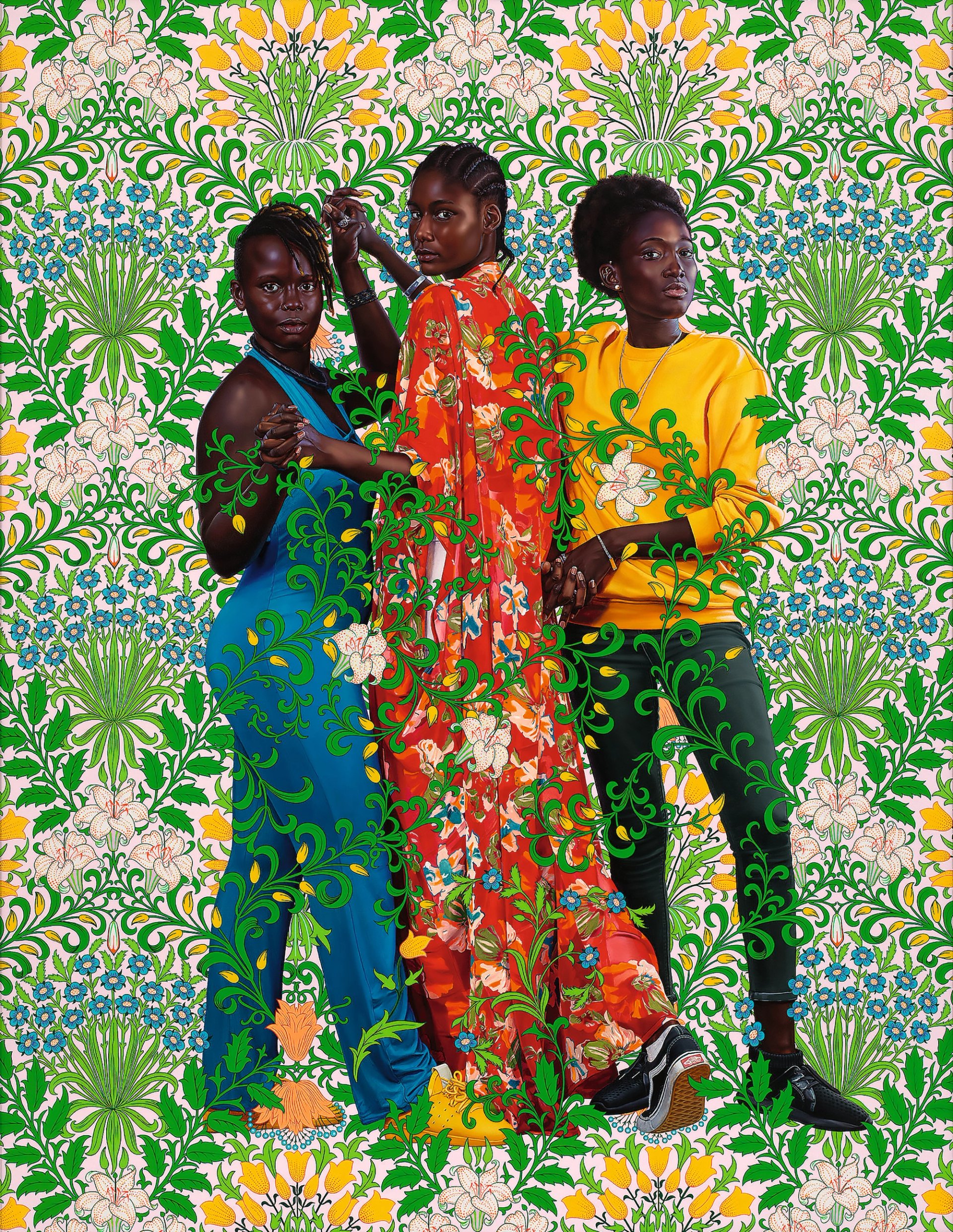

Kehinde Wiley’s The Three Graces (Coumba, Mariama, Rokhaya) (2023) © the artist; courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

Elsewhere, the Tracey Emin work the author picked is a 2022 monumental portrait in bronze of her mother. And for Frida Kahlo, Dempsey has chosen Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair (1940): the Mexican painter sits wide-legged in Diego Rivera’s suit, her long locks strewn Samson-style across the floor, her gaze unflinching.

“So much of the mean stuff has been covered,” Dempsey says. “I don’t want to give that more coverage.” Rather, she has sought out positive and interesting images, wherever possible, to, in her words, “be the change”.

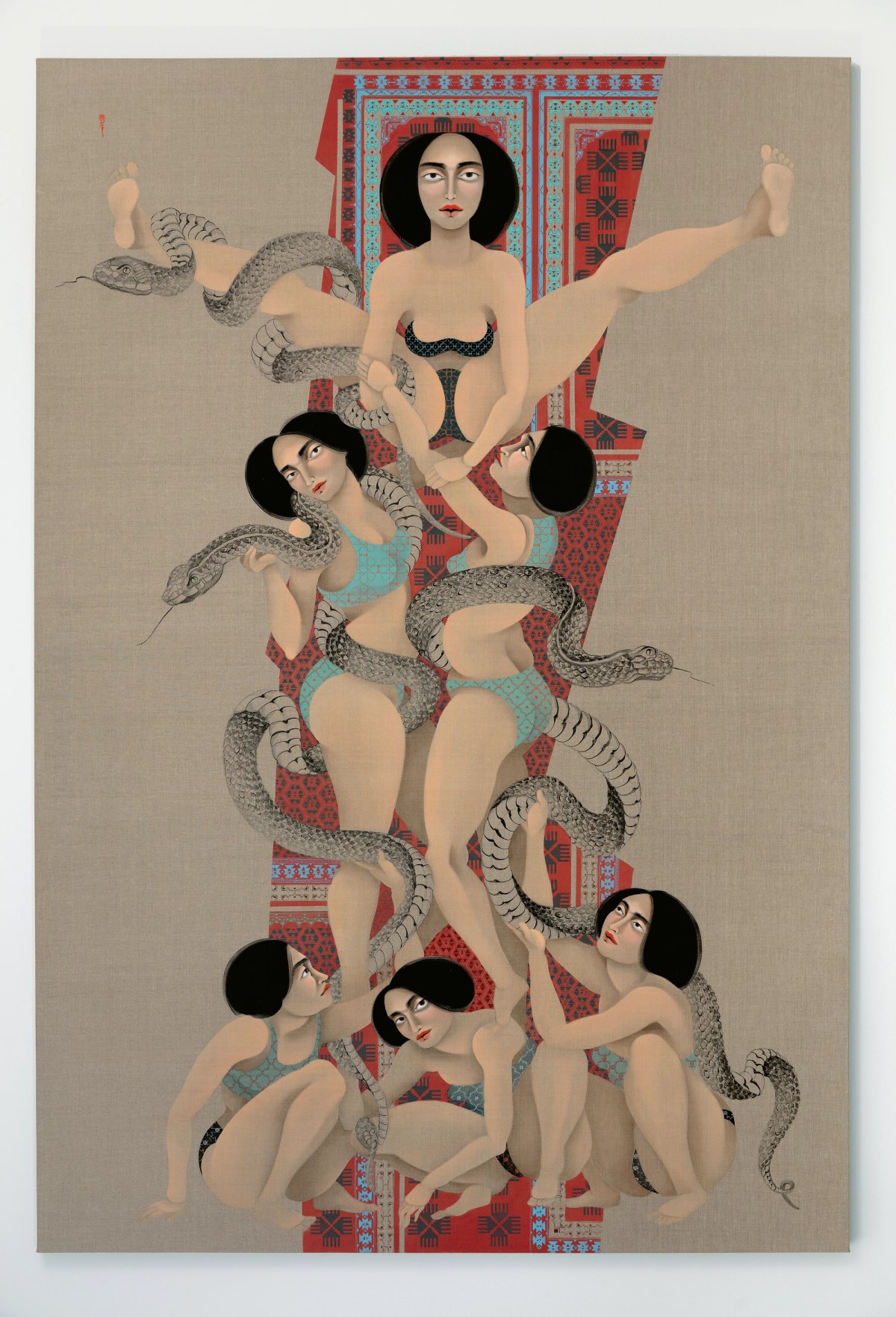

Dempsey has conceived of the book as an exhibition walkthrough, highlighting the Socratic nature of art history as a constant dialogue with itself. Including Kehinde Wiley’s Three Graces (2023) meant also including Peter Paul Rubens’s The Three Graces (1630-35), “which loads of people now wouldn’t know,” she says. Similarly, Yuki Kihara’s photographic work Nafea e te Fa’aipoipo? When Will You Marry? (after Gauguin) (2020) is in conversation with the named Paul Gauguin painting, bringing in questions of gender, sexuality and coloniality.

The final work is Rrap’s SOMOS (Standing On My Own Shoulders) (2024): a life-size bronze cast of the artist, at 73, literally standing on the shoulders of another cast of herself. “I was thinking about the usual problem of women artists and their lack of historical visibility,” Dempsey quotes Rrap saying, particularly as they age. As Dempsey puts it, that is ultimately what the book is all about: “Everybody deserves to be seen.”

• Amy Dempsey, The Female Body in Art, Laurence King, 240pp, £30 (hb)