Inuuteq Storch, the Greenlander artist who shot to international fame with his takeover of the Danish pavilion at the 2024 Venice Biennale, was fresh off of opening a major show at MoMA PS1 when Donald Trump renewed claims about taking over his home country.

Storch prefers not to talk about politics, he says over the phone from the Gothenburg, Sweden, where a new iteration of his Venice show has just opened. However, the Kaalaleq (Arctic Inuit) artist says: “In the beginning it was very shocking; now it is not so shocking. But it makes you feel something—and it's not good.”

The US president’s decision, in early January, to significantly ramp up his long-running rhetoric about taking over the autonomous Arctic island stunned not only locals but people all around the world. At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Trump seemed to rule out using military force—and applying tariffs to select EU nations—to achieve his aim. Yet his subsequent claim to have established “the framework of a future deal” on Greenland—with no details released as of yet—have left many uncertain about what the future may hold.

Storch says that many in his community "knew something was going to happen when Trump was elected“. Some artists have reacted to the situation through their work: one bone carver, for example, made a traditional carving “with Trump on it”. For Storch himself, the impact has been less direct but equally existential.

“We actually have quite good everyday life here and we want to preserve that,” he says. “We’ve been worried that our everyday life could change—and we don't know how it's going to change if that happens.”

These words carry particular potency from Storch, given that everyday life is the bread and butter of his artistic practice. His intimate, understated photographs capture the daily traditions and interactions of contemporary Greenlanders, each image a masterclass in composition and layering. In the series Keepers of the Ocean (2019), for example—primarily taken in Storch’s hometown of Sisimiut, the second largest city of Greenland, population 5,526—young people (Storch included) hang out and smoke; and an older woman bows her head as she walks, Greenland’s flag flapping behind her.

Photograph from Inuuteq Storch’s Keepers of The Ocean (2016-2022)

Courtesy of the artist and Wilson Saplana Gallery

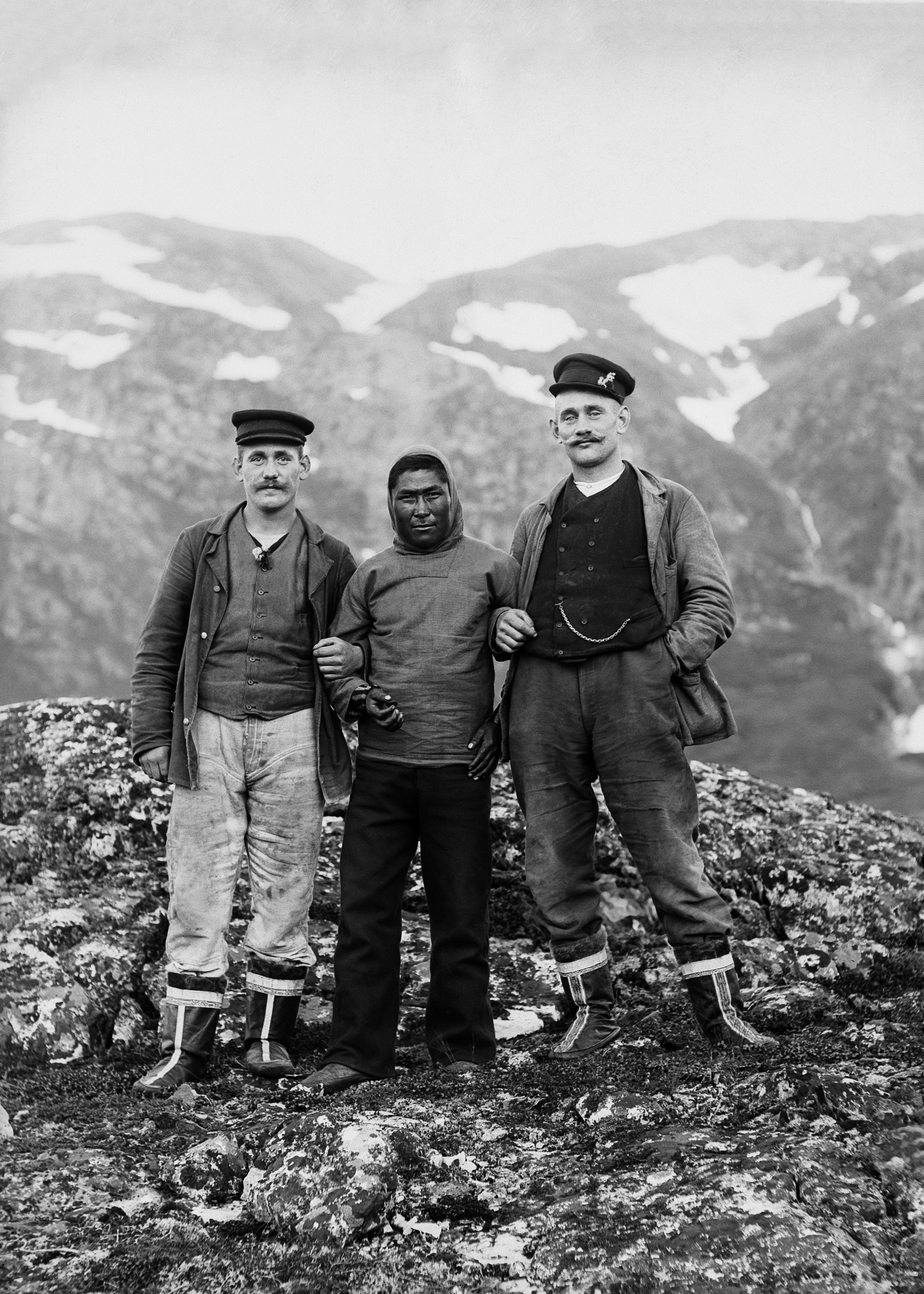

Storch has an equally strong interest in preserving images of Greenland’s past. He discovered, and digitised, for example, images by John Møller, Greenland’s first photographer, active in the late 19th and early 20th century. For Mirrored (2021) on view at Gothenburg’s Hasselblad Center, Storch pairs Møller’s images of foreigners—colonial officers, explorers and more—with his own pictures from Keepers of the Ocean, artfully bringing to mind questions about resistance, colonial power and their legacies across time.

Storch emphasises that while Greenland is talked about as a former colony—first inhabited by Denmark in 1721—“we feel like we are still one, and that intensifies the will to fight against it”. Archiving, in this context, is an intrinsically political act, and sometimes Storch is an activist in more overt ways. Outside his Venice pavilion, he placed the words “Kalaallit Nunaat”—the Indigenous Greenlandic term for Greenland—in Plexiglass over the word “Denmark”. There, and in Gothenburg, a sculpted red-semi circle referencing Greenland’s flag acts as a mirror, juxtaposing different series together.

Photo from Inuuteq Storch's Mirrored (2021)

Courtesy of the artist and Wilson Saplana Gallery

The US has featured in Storch’s work. It appears in photographic series such as Soon Will Summer Be Over (2023), which were taken in Qaanaaq, one of Greenland’s northernmost towns, where 27 families were forced to relocate in 1953, vacating their ancestral hunting grounds in Uummannaq to make room for the US military’s Thule Air Base. These images address melting glaciers and disappearing hunting traditions, but also a daily existence steeped in Western commercialisation: one man sits at a kitchen table, Brooklyn New York written on his t-shirt, a toy snowman in a striped scarf perched on the windowsill beside him.

Image from Inuuteq Storch's Soon Will Summer Be Over (2023)

Courtesy of the artist and Wilson Saplana Gallery

It is present, too, in Storch’s education. He studied, after leaving the Danish School of Art Photography in Copenhagen, at New York’s International Centre of Photography, graduating in 2016—though he quickly found himself drawn back to Sisimiut. “With all the movies and all the influence you get from the Western countries, you think there are more exciting places, more life,” he says. “But you realise that where you live, even though there are fewer people, there can actually be more life.”

And so, while he loves to travel, his focus has remained on Greenland, and on sharing the stories of his home country’s people with as wide and varied an audience as possible. He makes most of his series into books, because “you can give them to people in a lot smaller places”. He has two book projects on the go: What If You Were My Sabine?, a "declaration of love for a person, for your own culture and East Greenland”, part of which is on display at MoMA PS1—and Knight’s Hood Poems (Narayana Press, forthcoming 2026), documentation of graffiti Storch found scrawled on the walls of a stairway in an apartment building in Nuuk, Greenland’s capital. It delves into some of the same ideas Storch has explored before, but “from a different place, so it needs a different voice”, he says.

Storch’s ultimate dream is to create a Greenlandic photography museum, somewhere in the territory, where Møller’s work would be presented alongside the work of up and coming photographers. There are very few spaces to exhibit currently, he says, but “the Greenlandic language is a very picture-based language. We describe everything as we see it—so a lot of photographers at home are very, very good.”

“It's a very big dream,” he continues. “I don't even think I'm going to achieve it in my lifetime, but bringing the idea will hopefully start the process in our society.” The education value, he says, could be immense.

Storch talks about how “weird” it is to see the fate of his country discussed by other nations, “fighting for their benefit“ without locals even having their say.

“Before, we had a life without being noticed and now everyone knows about Greenland and wants [to give an] opinion on the situation,” he says. “It could be a good thing for tourism—but the quiet life we used to have, I think I'm going to miss that part.”

There is no sense, though, that he is losing hope for the future, or for his mission to preserve Greenlandic history for the masses. “I've become very optimistic,” he says. “When I was younger, I was a lot less optimistic. But the young artists that we have are so good. Not only that, our culture is also becoming more respected at home, as well as globally. I think that’s a very good situation.”

- Inuuteq Storch: Soon Will Summer Be Over, MoMA PS1, New York, until 23 February

- Inuuteq Storch: Rise of the Sunken Sun, Hasselblad Center, Gothenburg, until 3 May