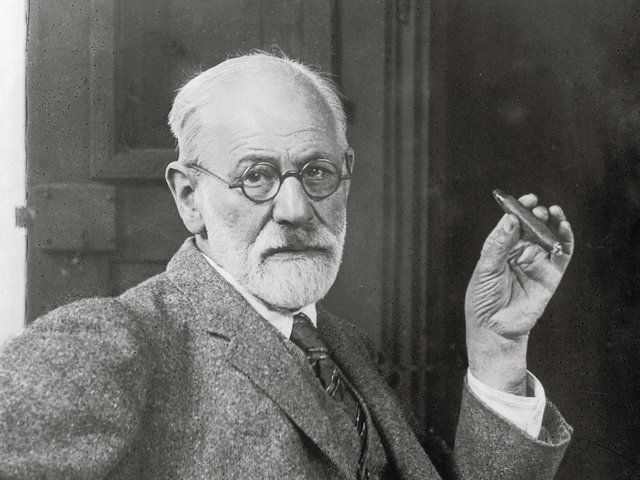

The Freud Museum in Hampstead, north London, is where Sigmund Freud lived the last year of his life—the father of psychoanalysis arriving with his family in 1938, ill with cancer and a refugee from Nazi persecution. It is an intensely evocative place, made all the more unique by the museum’s policy of inviting contemporary artists to respond to it.

Even though they had fled Vienna, the Freuds managed to bring many of their most precious possessions to 20 Maresfield Gardens, most notably the contents of Sigmund’s study and consulting room, including his remarkable collection of around 2,000 Roman, Egyptian, Chinese and Mexican antiquities, and of course his iconic psychoanalytic couch. Today all of this remains exactly as it was in Freud’s day: books and artefacts crowd into cabinets and cover every surface, with rows of ancient figures densely arranged across the large desk from where, even in his final months, Freud would write.

The house opened to the public in 1986, and one of the first artistic responses to its history and contents was Susan Hiller’s 1994 vitrine installation After the Freud Museum, now owned by the Tate and described by the artist as “a collection of things evoking cultural and historical points of slippage: psychic, ethnic, sexual and political disturbances”. Another memorable artist-disturber was Sophie Calle, who in 1999 spread her wedding dress across the hallowed couch and slyly interspersed personal keepsakes and intimate texts among the museum’s reverentially preserved artefacts; and another was Mark Wallinger, whose 2016 take on Freudian notions of doubling and self-reflection involved installing a mirror across the entire ceiling of the study.

I will also never forget Sarah Lucas’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle (2000), an exuberant exploration of the Freudian forces of Eros (desire) and Thanatos (death) which included slumping a mattress over a cardboard coffin in Freud’s bedroom and staging a sexual congress between two of Freud’s dining room chairs, decked out in male and female underwear and conjoined by a fluorescent strip light.

Now the museum is ushering in its 60th year with another radical series of interventions. Housekeeper by the British artist Cathie Pilkington channels the largely overlooked figure of Paula Fichtl, the Freud family’s devoted housekeeper. Fichtl joined the household in Vienna as a maid in 1929 and remained in their service until Anna’s death. One of her special duties was the care of Freud’s library and beloved antiquities. “Paula knows her way around here better than all of us,” Freud would say. “For every tiny piece she knows the right place.”

Unsettling precise order

Pilkington’s exhibition gives a new subversive agency to this loyal servant. In Pilkington’s hands, Fichtl takes on the persona of what she terms a “housekeeper poltergeist”, who stealthily disrupts this hallowed shrine to psychoanalysis, unsettling the precise order of Freud’s artefacts and slyly inserting some disquieting new elements.

Amid the objects in Freud’s study it is initially hard to spot Pilkington’s sculptural interlopers. Peeping out from among the figurines on the desk is a polychrome statuette of a multi-breasted goddess with long white socks and dainty red shoes, while on a mahogany plinth previously occupied by a Roman bust, another miniature naked figurine strikes a pose in racy stilettos. A horse’s head and a faceless fur-collared female bust appear on a tabletop and disembodied plaster limbs nestle on folded blankets.

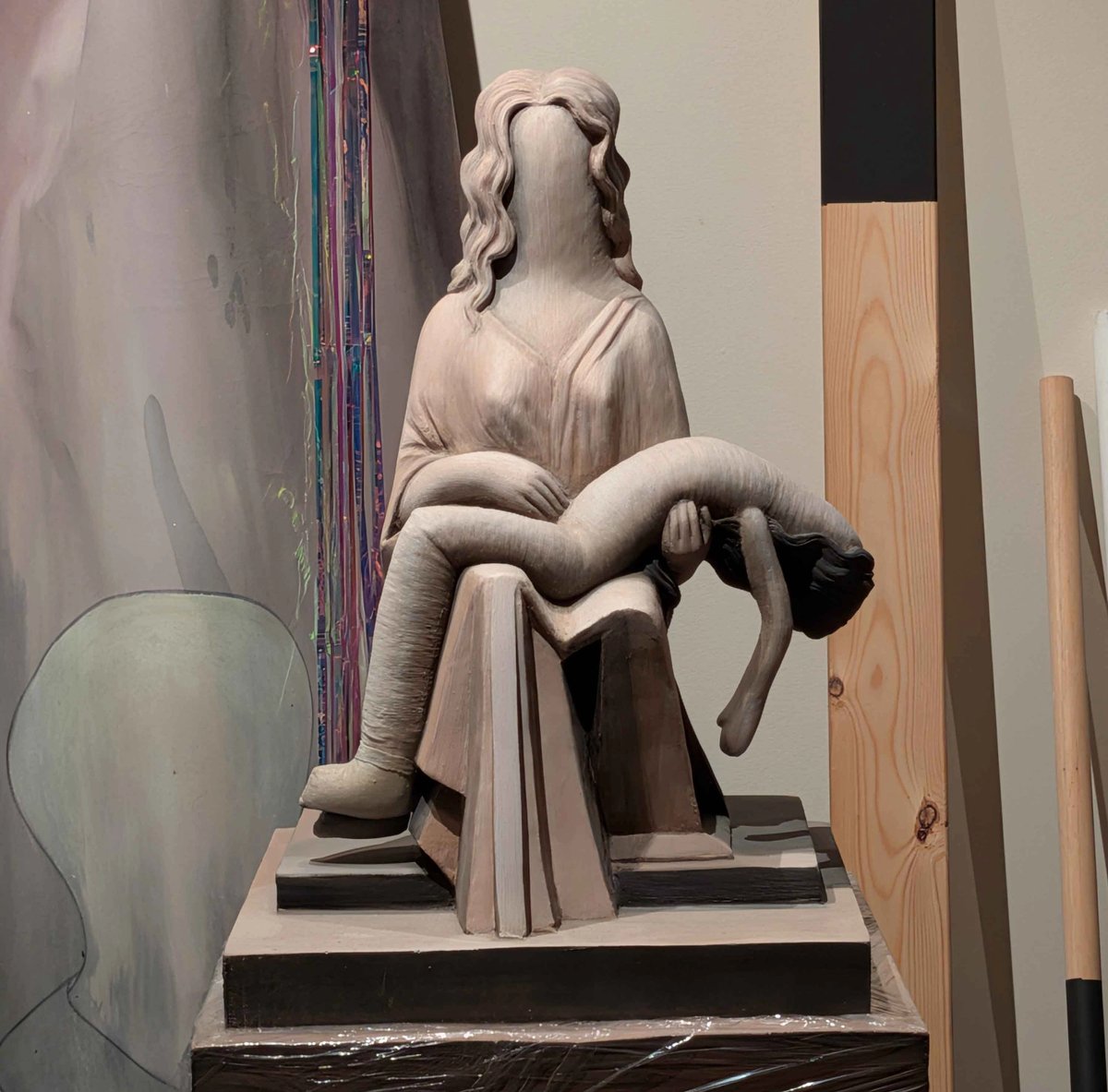

Cathie Pilkington, Herself (2019) in Housekeeper

Courtesy of Cathie Pilkington and the Freud Museum London Photography: Perou

In the dining room other new occupants continue to feed into the Freudian concepts such as the uncanny (or unhomely). Pilkington’s 2003 sculpture Curio, for example, features a disconcertingly ageless girl who sits at a dressing table piled with kitsch figurines glazed a gleaming chocolate brown. Upstairs, subtle subversion has been jettisoned, with Pilkington converting Freud’s bedroom into a dreamlike storeroom filled with an overwhelming mass of drawings, sculpture, found objects and works in progress.

A new work, Strata (2025), fills an entire wall with a glass case bursting with items ranging from female busts to random plaster and fabric limbs. Some of these are tucked between folds of packing blankets, the sediment-like layers of fabric chiming with the work’s geological title as well as echoing Freud’s notion of the unconscious as an archaeological site, excavated through psychoanalysis.

Cathie Pilkington, Strata (2025) in the Housekeeper show

Courtesy of Cathie Pilkington and the Freud Museum London Photography: Michael Barrett

By playing with conventions of storage, accumulation, curation and preservation—as well as offering multiple analogies with Freudian archetypes, practices and theories—this brilliant infiltration of the Freud Museum manages simultaneously to destabilise and reanimate the Great Man’s legacy. It’s no mean feat.

• Cathie Pilkington: Housekeeper, Freud Museum, London, until 1 March