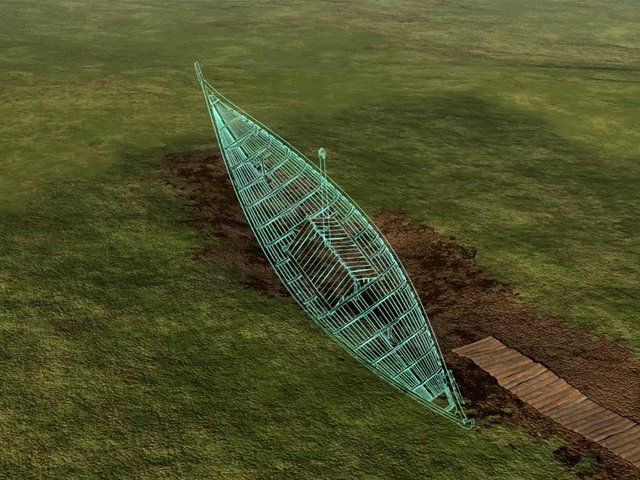

A more than 4,000-year-old artificial mound in Syria may be the world’s earliest known war memorial. Archaeologists identified patterns in the placement of burials and other finds in the mound—known as the White Monument at Tell Banat—and concluded that the dead may have been members of an army. It perhaps served as a unique memorial, visible to people for kilometres around.

“It was not until we recognised that there were patterns in those bone deposits that the elements fell into place. And that was pretty exciting,” says Anne Porter, assistant professor of Near Eastern archaeology at the University of Toronto, Canada, and lead author of the research paper published in the journal Antiquity.

It is unclear when the 22metre-high mound was first constructed, but it underwent modifications over the centuries. It took its final form at some point between 2450 and 2300 BC, when steps were built into the mound’s sides, making it appear like a step pyramid. Human bones were placed into these steps, representing around 30 individuals—both adults and younger people, ranging in age from around 8 to 20. Egg-shaped slingers’ pellets used as weapons and the skins of donkey-like animals called kunga, often used to pull vehicles, were also buried in the mound.

Biconical pellets from Tell Banat North Photo: courtesy of the Euphrates Salvage Project

Porter and her colleagues recently re-examined the evidence from the White Monument, which was excavated in the 1990s (the site was submerged in 1999 when a dam was built on the Euphrates River nearby, and has not been excavated since). Their analysis showed that the kunga skins were buried with pairs of bodies, perhaps reflecting the remains of chariot teams; while elsewhere on the monument, in their own zone, people were buried alongside pellets, and so may have been foot soldiers.

Taken together, it appeared that the individuals interred in the mound were buried as if they had died in battle. “They were presented as if they had certain functions in an army, but you have to be careful with burials—people in the past used the dead to tell stories and paint pictures, so it’s difficult to be sure that what we see was how it actually was,” Porter says.

Although mounds of defeated enemies are known from ancient Mesopotamian sources, the care shown to the dead at Tell Banat indicates that these individuals were not enemies, but soldiers being celebrated. From the fragmentary condition of their bones, they had died some time before their burial in the White Monument, and had perhaps been brought from a cemetery or battlefield elsewhere.

Who the soldiers of Tell Banat may have been fighting is unknown, but there are two main possibilities: either they were caught up in a conflict between regional powers, or there was an internal conflict, Porter says.