A cliché in gallery press releases about artists of a certain age is that they are “among the most influential artists working today”. Often it is nonsense. But when it is said of the US artist Bruce Nauman, few would dispute it.

This month, artists in London will have the chance to explore Nauman’s work in greater depth at Tate Modern, in his first UK retrospective for 20 years. These artists follow successive generations who have mined Nauman’s diverse practice anew. The 78-year-old has been influential ever since he was an art student. Mary Heilmann has acknowledged her debt to Nauman’s radical practice when he was still studying at the University of California, Davis, in the mid-1960s. And his effect has been consistent in the decades since. Artists as diverse as Mike Kelley and Isa Genzken, Jenny Holzer, Ragnar Kjartansson and a host of YBAs including Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin have acknowledged Nauman’s influence.

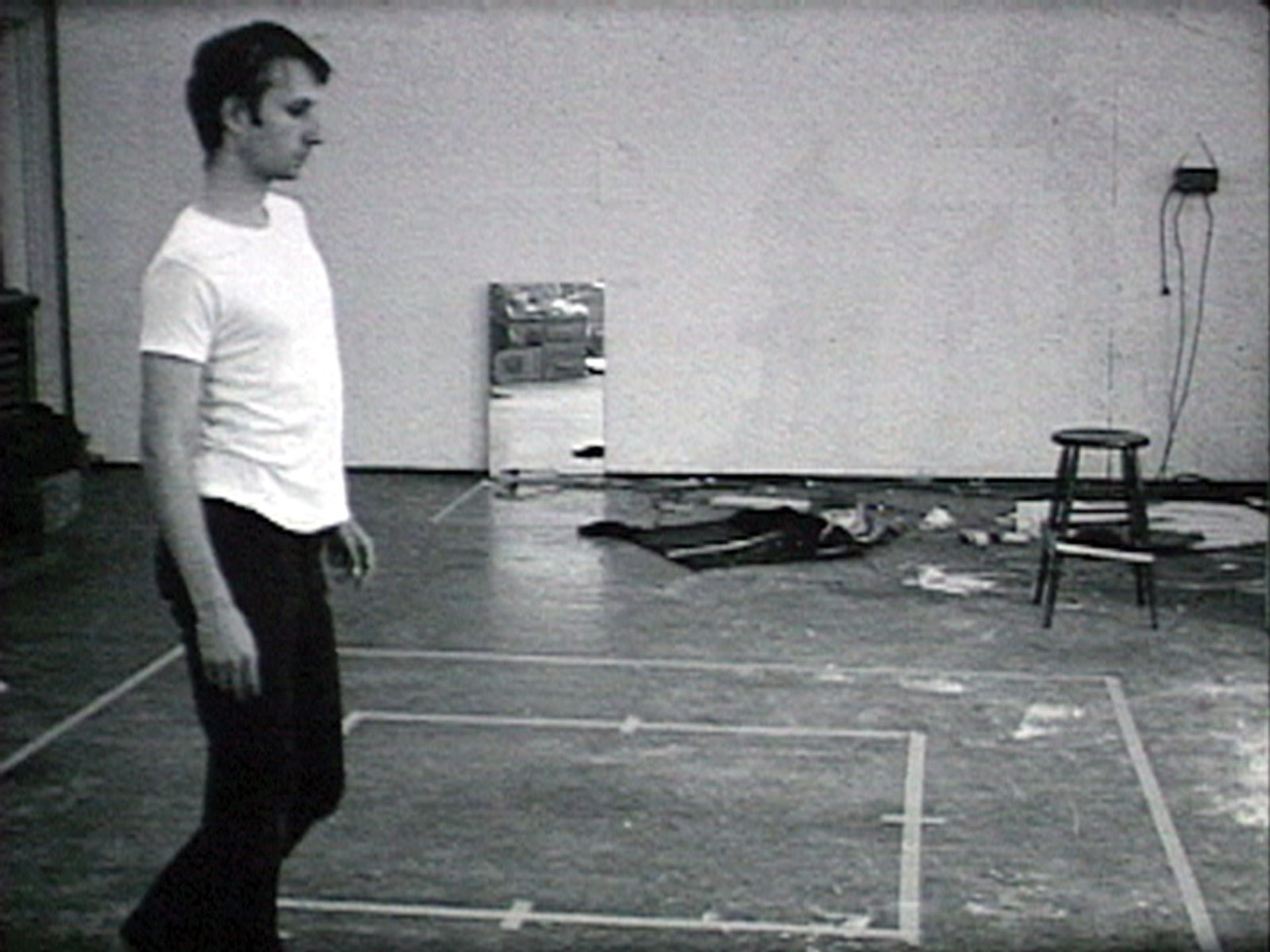

A still from Bruce Nauman's Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square (1967-68) Courtesy of EAI, NY; © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2020

Key to that enduring fascination is a slipperiness: while Nauman’s works are unified by a consistent rigour and pared-down toughness, the forms they take—video, performance, neon, sculpture, sound—and the meanings they conjure, are myriad. That elusiveness keeps artists guessing and pondering Nauman’s work, seeking an equivalent richness in their own practice. Here, three artists describe his effect on them.

Adham Faramawy Courtesy of the artist

Adham Faramawy

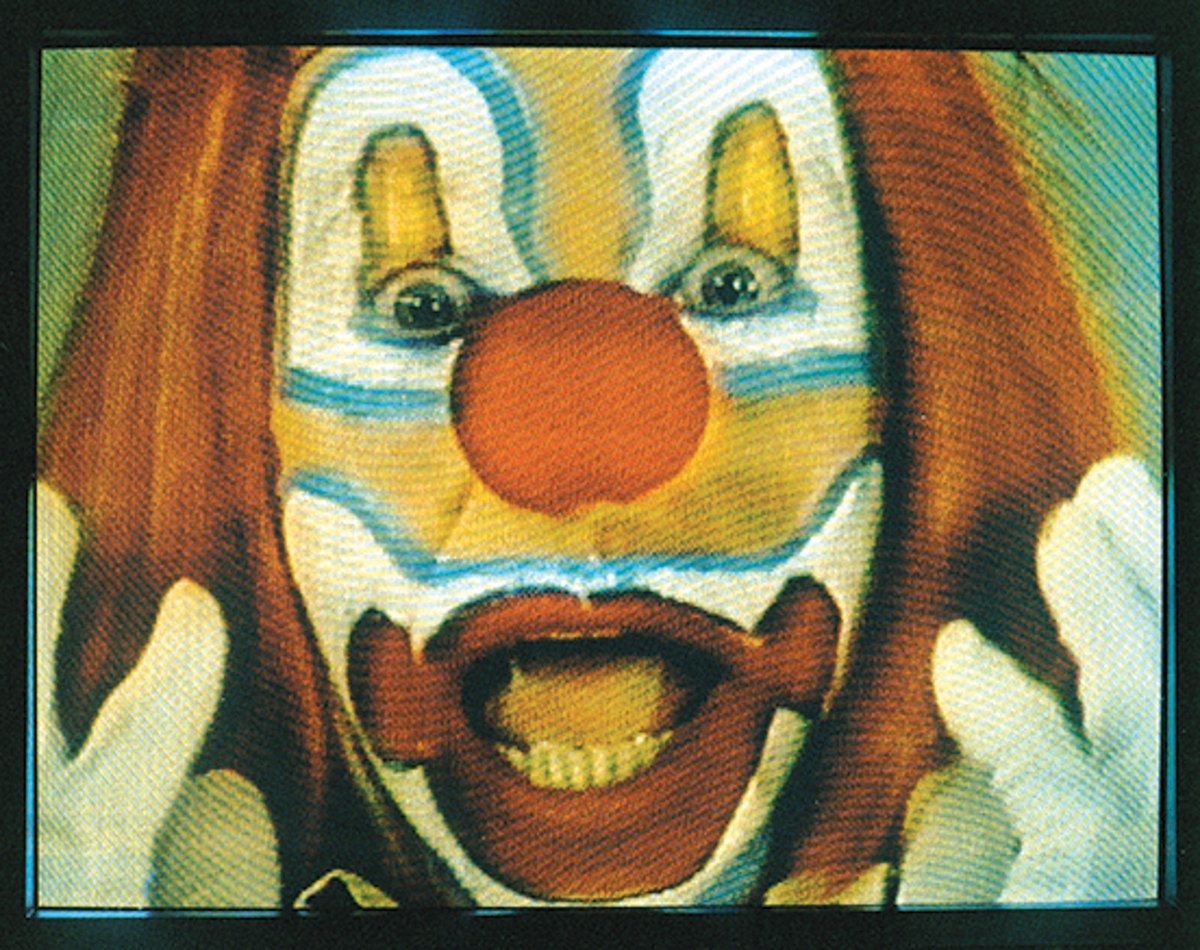

“I think the first Bruce Nauman piece I saw was the photograph Self Portrait as a Fountain (1966-67). I was about 14 and the piece opened me up to the idea that art can be funny, caustic and irreverent. And, along with early videos by Yayoi Kusama, Andy Warhol and Jack Smith, he informed the ways I approach performance for camera and the body as a subject. Nauman’s installation of video on TV monitors with pieces like Good Boy Bad Boy (1985)—along with work by Nam June Paik—excited me to explore the possibilities of moving image as a sculptural material where meaning can be confusing, sticky, slippery and unstable. These were works I loved as a teenager and they stuck with me through art school, becoming foundational to my approach to sculpture and moving image.”

Jacolby Satterwhite © James Emmerman

Jacolby Satterwhite

“Bruce Nauman was really amazing for me because he used objectivity around his body and his name as a measurement device—spelling his name, [casting] the negative space between the chair, [which] he set in concrete [A cast of the space under my chair (1965-68)]. His body was basically the centre point for the way that he mythologised space. He’s the nucleus for a certain kind of performance strategy that you see throughout art history. I loved the way that his body was a site for sculpture production. He really did allow me to understand that I could take my mother’s drawings and trace them with my hand and make these digital landscapes and perform on the green screen. My body shows up in performance pieces in public and it also shows up in the CGI worlds that I create. And the costumes I create are an extended format sculpture that may be 3D printed or may be green-screened, may be performed live, may be turned into an album. The limitlessness of expression is what I learned from Bruce Nauman.”

Rashid Johnson Photo: Eric Vogel

Rashid Johnson

“I always joke that if anyone tells you that they understand Bruce Nauman’s project [body of work] that you shouldn’t trust them, because I think it’s one of those projects that’s so nimble and so complicated and really marries […] a sense of poetry and the opportunity and sophistication that poetry provides with a sense of critical and conceptual investigation and exploration. And creating that relationship, that dichotomy, and giving them a place to thrive, I think that Bruce Nauman does that in ways that are just mind-blowing to me. And fascinating, and fun.”

• Rashid Johnson was speaking on The Art Newspaper's podcast A brush with... Rashid Johnson

• Bruce Nauman, Tate Modern, London, 7 October-21 February 2021