Paul Dobraszczyk’s sprightly and somehow faintly optimistic book is framed by two depressing episodes. In August 2020 and June of this year, police raids took place to dismantle art installations in east London. The primary targets of these swingeing displays of state power—ballet dancers, singing model sharks, a delicate cloud of bamboo rods and steel cables—weren’t hurting anybody; the legal pretext for the raids, a mangled blend of planning regulations and emergency powers introduced under cover of the pandemic, was flimsy and unconvincing. The fact that the arts charity that commissioned the installations is also a co-publisher of Architecture and Anarchism lets us know that it’s unlikely to be unsympathetic to their side of the story; even so, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that to build “without authority”, especially in an imperfect democracy such as the UK’s has become, is to court violence. So why would anyone do that?

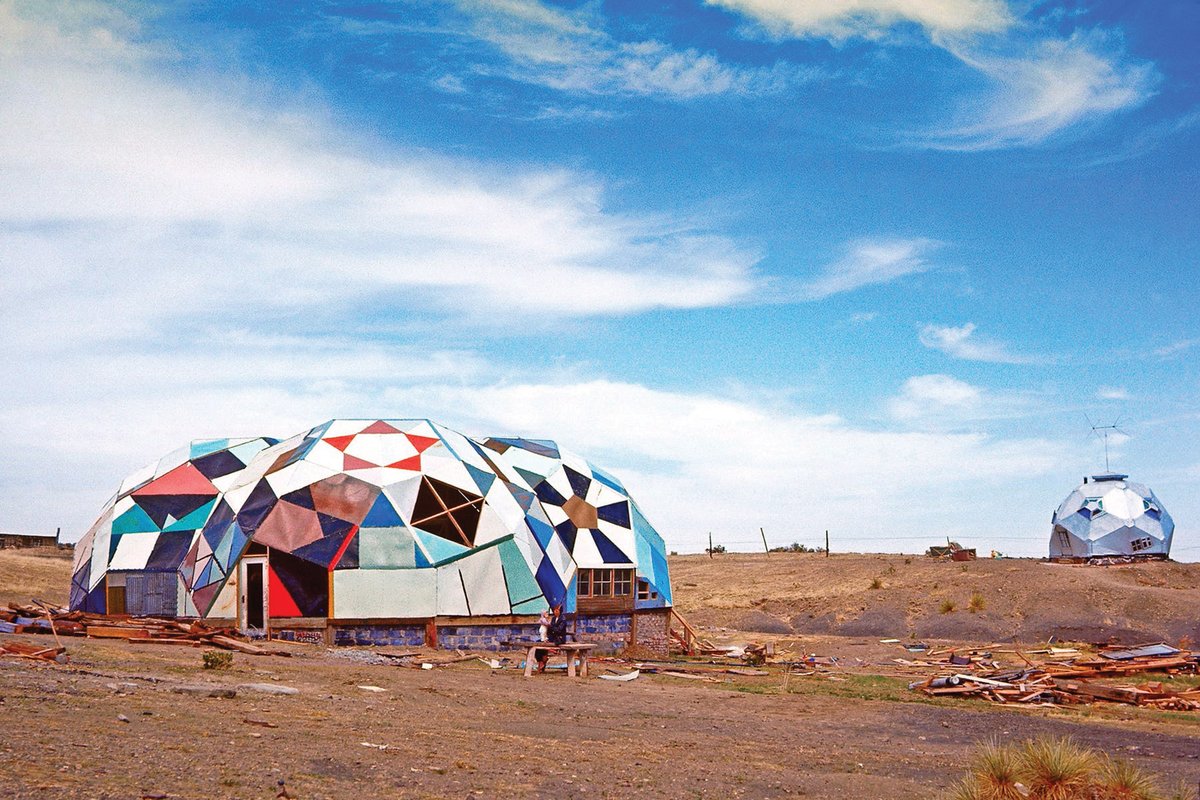

The main part of the book is a series of case histories of attempts by individuals and communities to regulate aspects of their own lives by taking control over their living spaces. There is necessarily a pretty wide spectrum of humanity on show—squatters, hippy communes, desert cults, self-build co-ops, hoboes, climate protesters, allotmenteers—and the outcomes they achieve vary correspondingly. Appropriately for a tradition that’s all about taking utopian ideas and giving them concrete form, we learn a little about the paper dreams of William Morris in the 19th century, then proceed via the funky geodesic domes of Drop City, Colorado, the glorious chimeras of Constant Nieuwenhuys’s endless imaginary pleasure palace “New Babylon” (designed from 1959 to 1974) and the only scarcely less fantastical designs of Archigram, to the plausible, fine-grained speculative fiction of William Gibson.

Arty countercultural settlements often function as the shock troops of gentrification

Theory is kept to a brisk minimum, but Dobraszczyk notes a distinction between the individual and the community, “freedom from” and “freedom to”. He points out that self-regulating groups might be more or less “radical”, and correspondingly less or more engaged with the “conventional” world around them (arty countercultural settlements often function as the shock troops of gentrification, for example). He notes the irony that people choosing to live in such a way are much likelier to spend their days enmeshed in byzantine planning and building regulations, and stuck in endless community meetings, than the rest of us.

With a book that inclines towards breadth rather than depth, there are bound to be quibbles about what’s in and what’s out. I’d like to have seen Nubia Way in south-east London included in the pantheon of Walter Segal self-builds: it was set up by the first Black British housing co-op, against the wishes of the National Front. There are too many jumbled-up bricolages of random disjecta and performatively fragile peri-apocalyptic shacks for all of them to have something unique to say. In the relatively small number of projects that are shaped by some over-arching aesthetic or stylistic intent, which I appreciate is not the point in the majority of cases, one often notes a certain infantile quality: the “earthships” of New Mexico and beyond, the Hundertwasserhaus in Vienna, the “hobbity” huts of Lammas in Pembrokeshire. Although, one notes, these last have proved vulnerable to fire—another example of authority and violence, maybe.

Paul Dobraszczyk, Architecture and Anarchism: Building Without Authority, Antepavilion/Paul Holberton Publishing, 248pp, 180 colour illus., £25 (pb), pub. 1 September 2021

• Keith Miller is a commissioning editor and writer for the Telegraph and a regular contributor to the Literary Review and the Times Literary Supplement