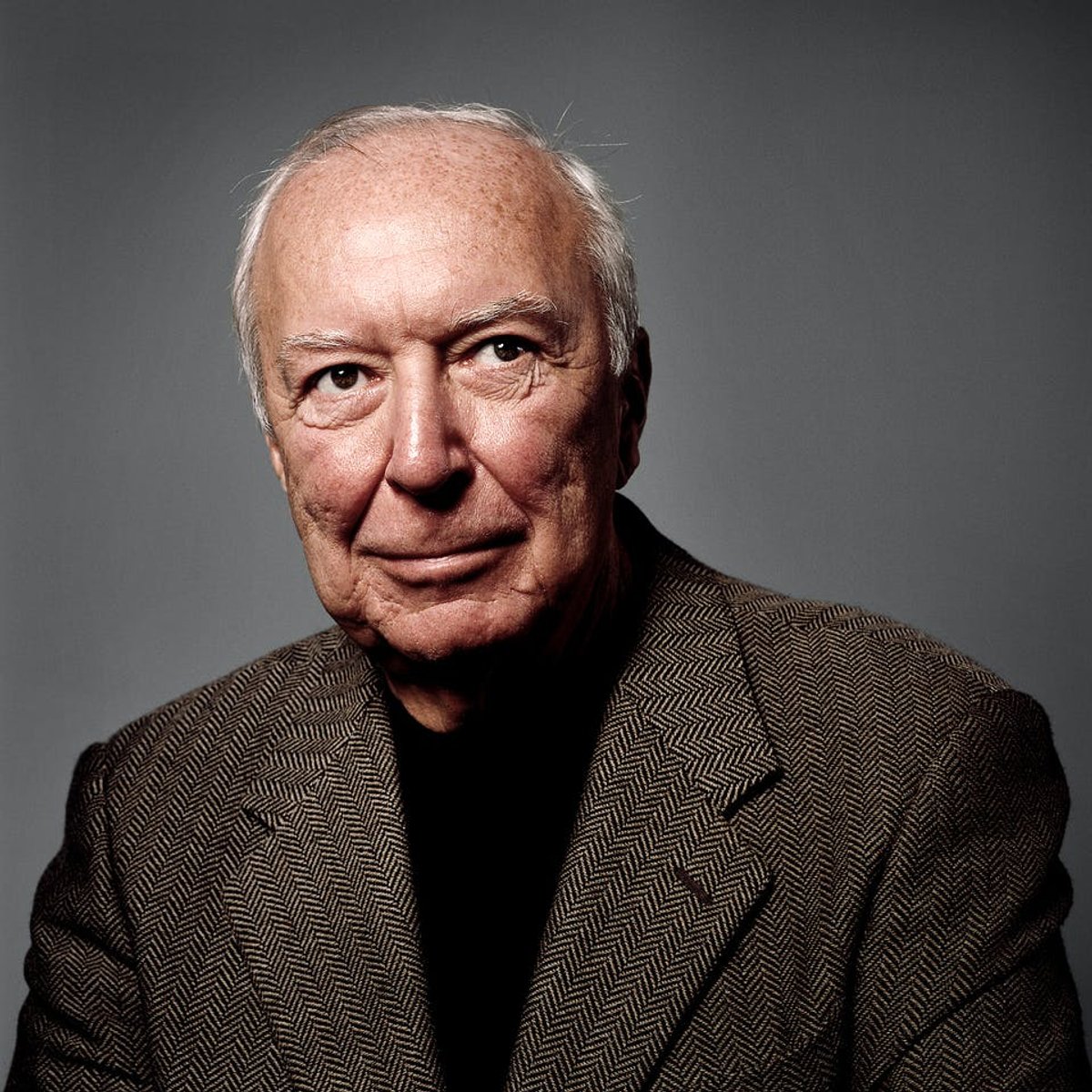

Jasper Johns is not only the most famous American artist alive—with the highest auction record for any living artist going to his 1959 painting False Start, which sold for $17m back in 1988—he is also notoriously solemn, grave and highly earnest, suffering fools badly and is resistant to most outside attempts to elucidate or simplify his oeuvre. That same oeuvre began in 1954 at the age of 24 when, like Francis Bacon, he destroyed all his earlier work to start anew. And the vital importance of the paintings, sculptures, drawings and “assemblies” he created over the next ten to 15 years made him, without challenge, the most innovative, inventive and brilliant artist anywhere, let alone in America.

This work not only heralded and outbid every subsequent movement, from pop to conceptual art, it also laid down a set of challenges to the very nature of artistic “re-presentation” that are still open to debate by scholars of semiotics and philosophers of the image. This work, strictly dated from just one decade, 1955 to 1965, will demonstrate its undimmed punch and feint at Washington, DC’s National Gallery of Art from 28 January—a show of “Greatest Hits” sans pareil. And there, of course, is the nub of the Johns conundrum that is continually spoken everywhere except in the vicinity of the Grand Old Man himself or his cohorts, a problem brought to the fore by his 1996 exhaustive full-scale retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art—bluntly, has it been downhill from there on?

Some of this may be attributable to status or straightforward spite, but there lingers a barely concealed consensus that Johns’ work has lost the avant-garde edge, the sheer energy and dazzle, and that if he remains a great draughstman and printer, his talents are inherently “graphic” rather than painterly. To form one’s own response to such sniping, there could not be a more revelatory exercise than to go to the Whitney Museum’s Picasso and American Art (until 28 January) where Johns has the honour of being the only living artist in the show and the last room is largely devoted to his recent variations on the ?master, one whose late work was also ?notoriously misinterpreted in his time.

Jasper Johns, Perilous Night (1982) National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

The Art Newspaper: The title of your upcoming show at Washington’s National Gallery of Art is An Allegory of Painting. One of the definitions of allegory is a “description of one thing under the image of another”, would that be appropriate ?

Jasper Johns: I was not involved in the determination of the title. Maybe [the curator] Jeffrey Weiss’ text will explain the meaning.

Presumably as a young artist of 25 making these works, your intentions were far more straightforward, perhaps even relatively unthinking and spontaneous?

The motivating forces were largely unconscious and the intention and the making seemed to be one and the same.

The thinking was spontaneous. Of course, the making often involved the usual delays—measuring, building, etc, even laziness, I suppose.

Are you sometimes surprised by the amount of critical commentary and intellectual interpretation, sometimes extremely arcane, that has subsequently grown up around these works?

They are unexpected but any initial surprise palls as one rather quickly becomes accustomed to commentary and interpretation, just as, I think, one easily might become accustomed to their absence, if one were faced with that. One has no audience in mind.

I think I was trying to see something, to see what seeing consisted of, to play with seeing and saying, while noticing that being alive involved certain complexities, ambiguities and contradictions

At the time you made these works was there any subversive or contrary intent, for example a flag almost as parodic flag?

None at all. Trying to remember now, I think that I was trying to see something, to see what seeing consisted of, to play with seeing and saying, while noticing that being alive involved certain complexities, ambiguities and contradictions. Hesitation seems of little use in these situations and most of what might pass for thought is expressed in actions and accumulations of actions, the materialisation of the work.

The dates of this exhibition cover a crucial ten years, 1955-65. Do you yourself consider this the most important decade in your development?

If you need me to pick a decade, I suppose that one would do. But maybe 1954 should be added to it, too. It is in this period that I matured a bit and became a functioning artist.

Is there anything you would change or alter in any of these works, anything with hindsight you might have approached even slightly differently?

Almost everything would be changed with hindsight, but the works would then be different works. Information and materials change over time, pushing us to different conclusions. Inevitably, the makeup of any artist changes, bits drop out and are replaced by other bits. That we remain as coherent as we do seems remarkable to me. I mean that it seems remarkable if I think about it. I do not usually think about it.

It is interesting to see your work at the Whitney Museum show on Picasso in which you dominate the last room—striking and relatively very recent work by yourself. Is Picasso a paradigm also in the way his late work was for a long while harshly judged by comparison with his earlier oeuvre, yet is now at last understood and greatly appreciated? You left it fairly late yourself to finally tackle Picasso, did you previously feel it might seem presumptive?

To think of someone is not to tackle them. Earlier, hoping to make paintings that I could feel were my own, I deliberately tried to avoid anything that I sensed was a reference or resemblance to the work of others. This didn’t mean that I didn’t think of others and their work. Later, as motifs, I suppose, some of this thought showed up in what I was doing.

How do you feel about your work being celebrated as the origin of Pop art or indeed Conceptual art?

Such ideas don’t interest me very much. There are lots of ways to look at cause and effect, and at continuity.

The kinds of meaning and order that we may find in works of art, I suspect, rarely duplicate those that the artists who made them might find

The National Gallery exhibition identifies a narrative or “internal logic” in your work covering the relationship of four motifs: “Target”, “Mechanical Device”, “Stenciled Naming of Colors” and “Imprint of the Body”. Was such a narrative explicit for you at the time?

The kinds of meaning and order that we may find in works of art, I suspect, rarely duplicate those that the artists who made them might find. Most artists don’t concentrate on the past, and hope that their work gives us a sense of the present. Any artist probably feels that his work is logical. That doesn’t mean that it was pre-imagined, only that it seemed unavoidable, inevitable.

What about the Cage notion of chance, of the random within your system?

John Cage had a much more formal conception of chance than I. Contact with his ideas enlarged my own vocabulary of possibilities, but I am chance-friendly only selectively.

What was your relationship, as a painter, to Duchamp and his ideas? You took his notion of the “readymade”, objects that already existed, and then turned them back into actual paintings or sculpture created by yourself.

I believe I remember seeing Duchamp’s LHOOQ in a book when I was a student at the University of South Carolina in the late 1940s, but I think it had no meaning for me. I became interested in Dada in the 1950s, when people began to mention it to me in relation to my own paintings, and then I visited the Arensberg Collection and read Motherwell’s The Dada Painters and Poets. I later met Duchamp and enjoyed seeing him ?occasionally but we rarely discussed ideas in any direct way.

Your commitment to printmaking, the technology of reproduction, seems like an extension of the readymade idea, the image of an image?

From my earliest simple drawings on stone to complex combinations of intaglio techniques, printmaking has offered a rather clear learning experience, different from anything that painting provides. It gives pleasure similar to what gardening with the help of another person might bring. The reproductive aspect of the activity is an aside, a bonus.

If your earliest work could be seen as wryly dry and cerebral as opposed to bombastically expressionistic, do you feel all artists get more expressionistic as they age, that a temptation to emotion emerges?

I don’t know.

You also have a large retrospective of your prints opening at the National Gallery in March. How different is the impression of your work to be garnered from such thorough print shows? Does the cross-hatching motif of your later paintings derive from the burr and cross-hatching of the printmaking processes?

No. It began as an attempt to reconstruct from memory a pattern that I had seen decorating the surface of a passing automobile.

The mis-naming of colours suggests Magritte’s use of contradictory words in his paintings and yet your works are rarely linked to Surrealism.

There is at present a Magritte exhibition at LACMA that shows work by a number of more recent artists who in some ways echo or connect to concerns of his. A few paintings and lithographs of mine are included.

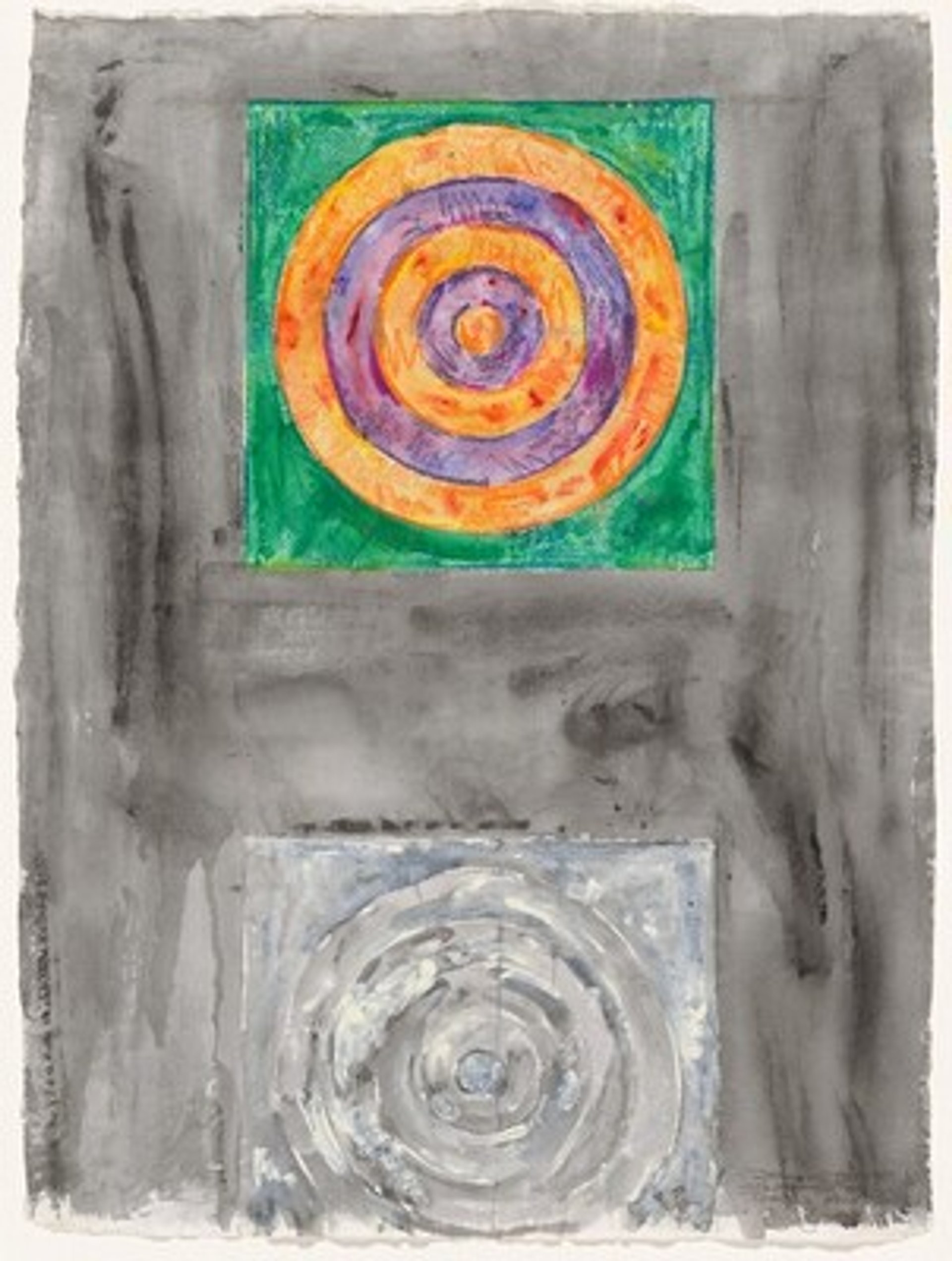

Jasper Johns, Targets (1967-68), chalk, paint, and graphite on wove paper sheet National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

The constant graphic imperative of your work would suggest drawing is crucial to the process. Or do you resist such an over-emphasised distinction between drawing and painting?

I have always enjoyed drawings. In them, thought seems more concentrated, more suggestive.

I try not to destroy what I have begun. I think this began as an attempt to remedy a childish habit of not finishing most things. Sometimes destruction is the only solution.

Can you reveal a little of the practicalities of your every day process, how you actually start work in the day, the stages of creation from their most basic and banal? You famously destroyed your earliest work in 1954, to start afresh as did Francis Bacon. Do you still scrap work, abandon it, or carry on working through with it until eventually satisfied?

I try not to destroy what I have begun. I think this began as an attempt to remedy a childish habit of not finishing most things. Sometimes destruction is the only solution.

I remember being intrigued at a show of early Chris Burden performance relics that some of the most provocative works were in your own collection. Do you still collect other artists, including those, like Burden, who might seem at an unusual angle to your own perceived aesthetic?

Occasionally, I acquire drawings or small works, but there is no programme or order to the activity.

Biography

Background: Born in 1930, Augusta, Georgia; educated at University of South Carolina, 1947-48

Currently showing in: Picasso and American Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (until 28 January); Magritte and Contemporary Art: the Treachery of Images, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (until 4 March), Jasper Johns: an Allegory of Painting, 1955-65, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 28 January-29 April

Upcoming shows: States and Variations: Prints by Jasper Johns, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 11 March-3 September

Selected solo shows: 2003: Past Things and Present: Jasper Johns since 1983, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Travelled to: Greenville County Museum of Art, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Institut Valencia d’Art Modern, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin; Jasper Johns: Numbers, Cleveland Museum of Art. Travelled to Los Angeles County Museum of Art; 1996: Jasper Johns: a Retrospective, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Travelled to: Ludwig Museum, Cologne and Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo; 1977: Jasper Johns, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Travelled to Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris, Hayward Gallery, London, and Seibu Museum of Art, Tokyo

• To read more of our best artist interviews over the past 30 years, click here for the full collection