The Cairo-based artist Ganzeer’s stencil of Egyptian riot police, bravely painted on the side of the Mogamma government building on Tahrir Square last month, is the latest in a long line of works of art that have flourished in Egypt’s streets since Hosni Mubarak was ousted in February 2011. In Libya and Syria too, radical publishing and pamphleteering, street art and graffiti have thrived, even appearing in deeply conservative Saudi Arabia.

Murals for the dead

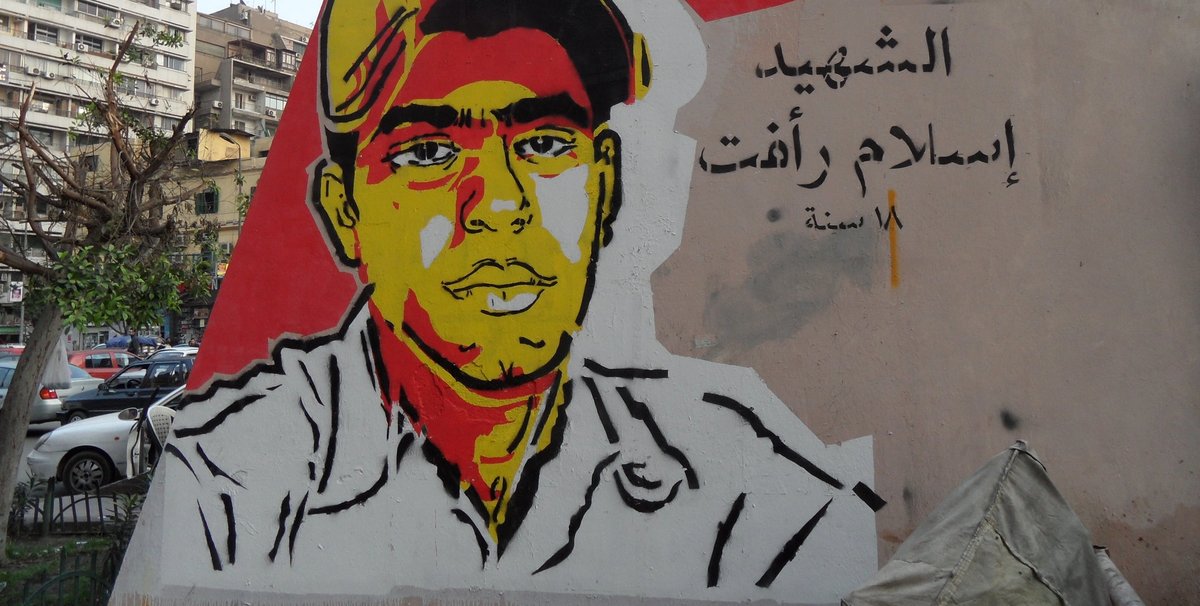

Egypt’s growing group of young artists working in the street, including Ganzeer, Keizer, El Teneen, Hosni and Hany Khaled, are engaging actively in the revolution. Ganzeer, 29, who exhibits his work both in and out of galleries (in a recent interview in Bidoun magazine, he said his gallery work is “the least satisfying” as it “is not relevant to life”), is painting a mural for each of the people killed during the 18 days of revolt that began in January 2011. Since this is believed to number as many as 850, this is a major undertaking.

“What is interesting to see in Egypt, and in all these countries, is that artists are not only going out into the city, they also become agents of change in society,” says Hans Ulrich Obrist of London’s Serpentine Gallery, who is chairing a discussion on art patronage in the Middle East as part of a summit at the British Museum and the Royal College of Art (12-13 January, see below). “If you think about it in terms of the Russian Revolution and Mayakovsky saying ‘the streets are our brushes, the squares our palettes’, it’s about art going beyond the museum and blurring the boundaries between art and life.”

Obrist also notes that there is a long-standing tradition, particularly in Egypt, of contemporary artists using the street to mount performances or install works. Indeed, several contemporary Egyptian artists, including Susan Hefuna and Hassan Khan, have used the city as a site for their work, both before and in response to the uprising.

Egypt has also attracted its share of international street artists. In October, German street art collective Ma’Claim was invited by the Goethe Institute in Alexandria to paint murals depicting the revolution in the city. Following the project, Ma’Claim member Andreas von Chrzanowski, who works under the name Case, went on to Cairo. There he stencilled portraits of Mina Daniel, an activist who was killed during protests in Cairo, and Khaled Said, whose murder by two policemen in Alexandria in June 2010 caused public outrage, on walls near the ministry of the interior. “I had to be careful, there was military everywhere,” says Von Chrzanowski.

The recent surge in street art has not been driven by artists alone. “There was a big rise in March,” says Daniel Stoevesandt, the director of the Goethe Institute in Alexandria. “Almost everybody was painting in the street.” Fatenn Mostafa, the founder of Art Talks: Egypt’s Visual Arts Foundation, says many young people took to the streets to express their frustration. “However, the most striking and expressive [murals] are by artists,” she says.

With the level of sophistication of many of the outdoor works in Egypt, the question now is how—or whether—to preserve them. The owners of the buildings in Alexandria bearing the Ma’Claim murals have agreed to keep the works, according to Stoevesandt. “But as they are graffiti we never know whether someone else might tag or paint over them.”

Whitewash

Mostafa says that Egypt’s ruling military council is beginning to whitewash some of the overtly political graffiti: “Many walls are being removed by Scaf (the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces) or pro-Scaf citizens.”

While the recent elections in Egypt have brought about a fresh wave of politicised street art, the commercial sector has also seized the opportunity to promote itself. “Some people have been hijacking the space and using it for private advertising,” Stoevesandt says. Internet providers, mobile telephone companies and soft drinks corporations are rebranding themselves as revolutionary, with signs such as “Make Tomorrow Better: Coca-Cola” appearing in the streets of Cairo. This commodification of the uprising is galvanising artists and young people to reclaim the streets once again.

In Libya, as in Egypt, pictorially complex murals decorate the streets. Muammar Gaddafi is the subject of much of the art, with the late leader often humorously depicted as a rat, an ape or a vampire. Mainly found in bigger cities such as Tripoli and Benghazi, Rana Jawad, the BBC’s North Africa correspondent, who has spent the past year in Tripoli, says murals started appearing almost immediately after Tripoli fell in August. “It happened so quickly,” she says. “Within five or six days it seemed every wall had a portrait that mocked Gaddafi.” As fighting between rival militias continues in Libya, graffiti are increasingly being used to show support for different political factions. “We are also seeing more elaborate works depicting general themes such as war, feelings of nationalism and the future of Libya,” Jawad says.

Many of the wall paintings are sophisticated, but, according to Jawad, there are no official plans to keep the work. “Some people say [the murals] are part of a new heritage and want to keep the more elaborate paintings, but others say that in a few years time some of the images might not carry the same meaning as they do now.” In the long term, hastily scrawled graffiti are likely to be incongruous with the image Tripoli will want to project when it reopens for business.

Al-Assad as Hitler

While revolution spread through Egypt and Libya with the help of Twitter and Facebook, in Syria graffiti were instrumental in sparking the uprising. “The revolution started in Syria because of a message written on a wall,” says Fatenn Mostafa. Borrowing a slogan that had appeared in Egypt and Tunisia, 15 youths scrawled “the people want the fall of the regime” on a wall in the southern agricultural town of Daraa in March. Their arrest and detention for ten days, during which time they were allegedly tortured, prompted protests that quickly spread through the country.

Political slogans characterise much of the street art found in Syria. Dubbed the “war of the walls”, anti- and pro-government protesters are voicing their support through graffiti. In July, supporters of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad attacked the US and French embassies in Damascus. Protesters sprayed the walls of the US embassy with graffiti calling the ambassador, Robert Ford, a dog. Yasmin Atassi, the director of Dubai’s Green Art Gallery who was last in her native Syria in September, says a lot of the graffiti consist of slogans such as “democracy” or “freedom”, although most is immediately erased.

In a show of solidarity with Syria, a black and white stencil of Al-Assad as Hitler, a collaboration between El Teneen and an anonymous Lebanese artist, appeared in Cairo in July and in Beirut in August.

As unrest continues to spread through North Africa and the Middle East, street art continues to be used to publicise injustice, and show support for various political or military brigades, even as a catalyst for attempts to bring down governments.

But, as Anthony Downey, the director of contemporary art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art in London, editor of ibraaz.org and a speaker at the summit says, the region has “antecedents in graffiti-based protests”, citing those against the Shah of Iran before his flight from Tehran in 1979 and the graffiti and posters used in Beirut during the civil war in Lebanon.

Historical precedent aside, what remains to be seen is whether street art in the region will have an artistic legacy. “Graffiti are a poignant and relevant expression of the current political climate,” says Mostafa. “But, as time passes, will street art still serve an important purpose and survive?”