In 1972, in Houston, the photography collectors John and Dominique de Menil asked Henri Cartier-Bresson to select his Grand Jeu—a group of works that the great French photographer, the creator of the term “decisive moment”, considered to be his own “master collection”.

Cartier-Bresson’s selection encompassed photographs inspired by the Surrealist circle of artists with whom he socialised in Paris’s Montparnasse; it included images clearly in debt to the cinematic style of his friend Jean Renoir; and it included happenstance street scenes from his life on the road, providing what would now be considered an authorial evolution of photojournalism through which his revolutionary political beliefs were served.

The French photographer’s original selection is to be exhibited in its entirety at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice from 11 July, after its original March opening was aborted due to the pandemic. The show is a collaboration between the Pinault Collection and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, with the support of the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson; between them they own all 385 works that Cartier-Bresson originally selected for the De Menils.

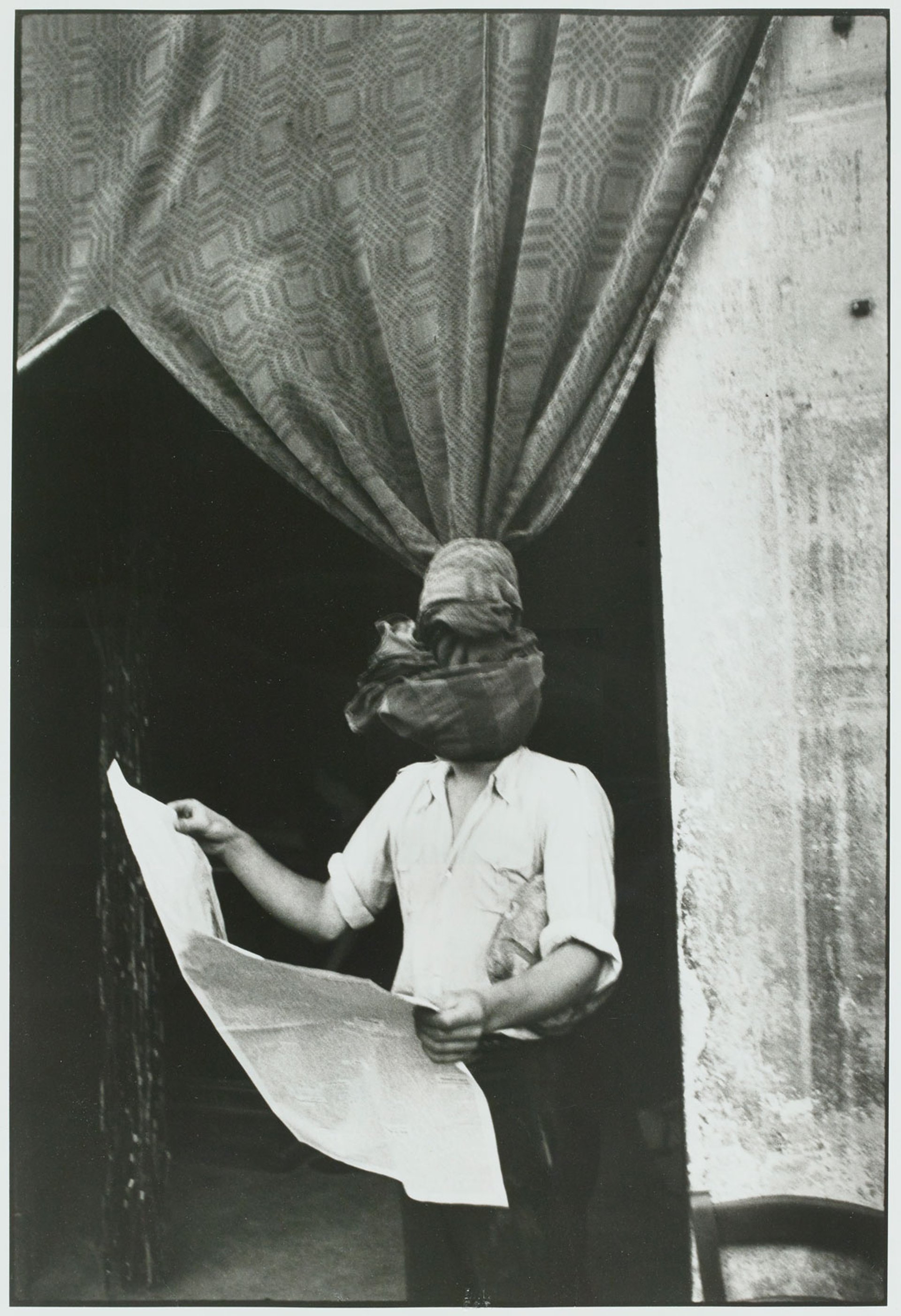

Cartier-Bresson's Livourne, Italie (1933) © Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

“The mere idea of presenting this extraordinary body of work for the very first time in Europe was a fascinating proposition in itself,” says Martin Bethenod, the director of the Pinault Collection.

Yet this exhibition will offer something more ambitious and contemporary than a simple re-showing of a late great’s archival imagery, because the exhibition’s curator, Matthieu Humery, invited five notable figures to create their own unique interpretations of Cartier-Bresson’s work. Humery’s co-curators are the billionaire businessman, collector and owner of the museum, François Pinault; the photographer Annie Leibovitz; the film director Wim Wenders; the writer Javier Cercas; and the art historian Sylvie Aubenas.

“The idea that a photographer could see how other people lived, make looking a mission, was an amazing, thrilling idea”Annie Leibovitz

Each curator was instructed to select 50 prints from the 385 and, then given carte blanche without any concern for chronology or a theme. In doing so, “a completely new Grand Jeu was created, but one that multiplies ways of seeing the master photographer’s work”, Bethenod says.

“Cartier-Bresson’s oeuvre lends itself to this type of interdisciplinary interpretation,” says Laurence Engel, the president of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. “It becomes an inexhaustible medium for stories, visual demonstrations, illustrating tastes, echoing personal experience and the work of those who are analysing it.”

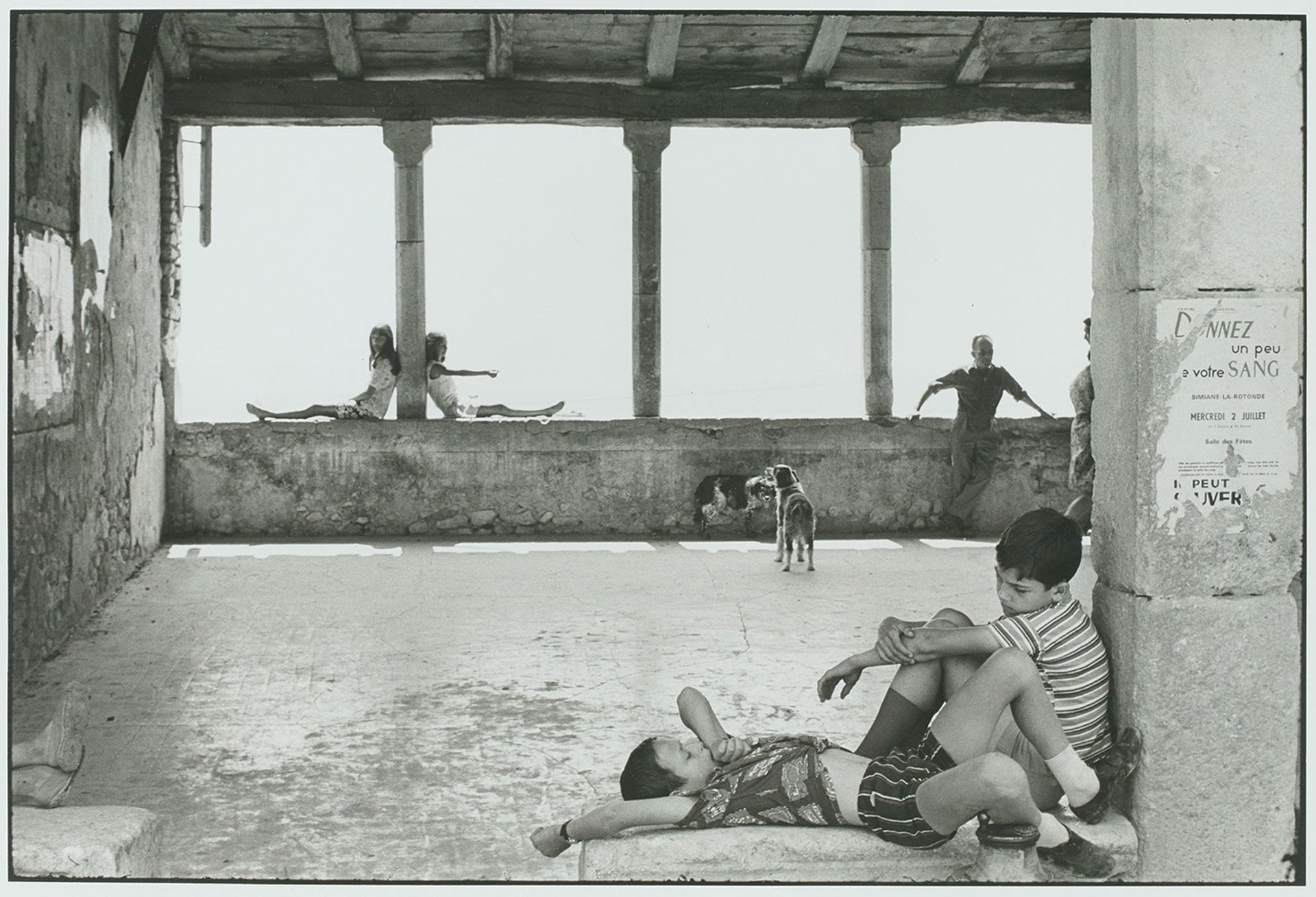

Cartier-Bresson's Simiane-la-Rotonde, France (1969) © Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

As a young painting student at the San Francisco Art Institute, the celebrated US portrait photographer Annie Leibovitz remembers discovering the photographer’s work in the book The World of Henri Cartier-Bresson, which had just been published. Writing in the exhibition’s catalogue, Leibovitz says: “Seeing Cartier-Bresson’s work made me want to become a photographer. The idea that a photographer could travel with a camera to different places, see how other people lived, make looking a mission—that that could be your life was an amazing, thrilling idea.”

Leibovitz remembers studying two of Cartier-Bresson’s most famous images: a portrait of the French artist Henri Matisse sitting in a grimy coop with his white doves, along with a carefully composed photograph of middle-aged friends having a boozy picnic on the hilly edge of a French river. Both are included in her selection. She calls Cartier-Bresson “an intuitive master of composition”.

The German film-maker and photographer Wim Wenders used as inspiration a solitary chance meeting with Cartier-Bresson in Paris in the late 1980s. “When everybody was leaving, he offered to drive me back to my hotel. All of a sudden, we sat in his small car together, just the two of us,” writes Wenders. “I glanced at him. He seemed so transparent, gentle, and kind, and also a bit frail.” The journey ended in silence, with Wenders overcome with shyness. “Why didn’t I ask him anything?” Wenders writes. “His silent profile behind the wheel of his car still appears to me when I look at his pictures. But his face won’t answer my question. Nothing will do that now, except his photographs.”

• Henri Cartier-Bresson: Le Grand Jeu, Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 11 July-10 January 2021