The prolific South African artist William Kentridge has spoken out about London’s usage of colonial era monuments, saying they are indicative of the UK’s struggle to reconcile itself with its violent colonial past.

“There are many, many imaginative solutions to dealing with the ongoing question of how to deal with [the UK's] shameful past,” the artist told The Art Newspaper before the sell-out performances of his new chamber opera Sibyl, staged at London’s Barbican Arts Centre (22-24 April).

“South Africa is ahead of the UK because we have such a shameful past, and yet we have built a consensus on that,” Kentridge said. “And you think: My God—[the UK] should take as a starting point that [its] history is blighted. The question should be: ‘How do we deal with our blighted past?' rather than defending it and saying it was nothing but a heroic history.”

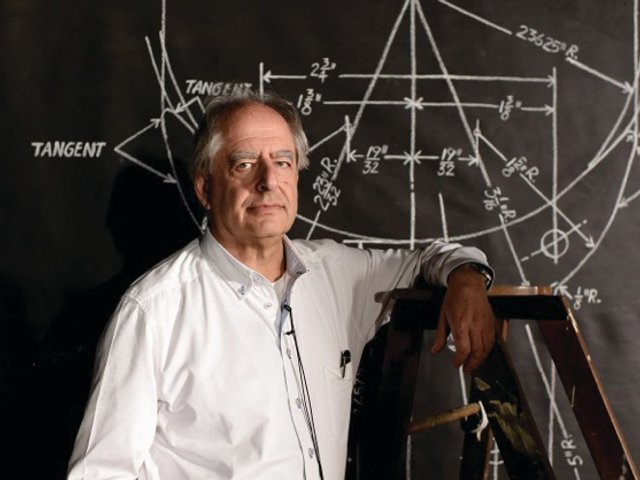

Kentridge’s comments come ahead of his major autumn retrospective at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, due to launch 24 September 2022, and as he is awarded Lifetime Achievement Award for printmaking by Queen Sonja of Norway on 20 June.

The art of politics

Kentridge was a student of political science as well as fine art in the 1970s, and originally started making prints and screen-printed posters for trade unions, student protests and theatre companies. Virtually all of his work reflects, in some way, on South Africa’s recent colonial past and how that has informed his identity as a Jewish South African man, the son of barristers who represented people marginalised by the apartheid system.

The artist told The Art Newspaper that he considers the toppling and sinking of the statue of the Bristol-born merchant and trans-Atlantic slave trader Edward Colston on 7 June 2020 to be a momentous moment for British post-colonial politics. “After [...] there seemed to be a fear that all comparable monuments were going to be destroyed,” he said.

Kentridge was particularly interested in the Mayor of London’s decision to then protect statues of Winston Churchill and other colonial era figures as Black Lives Matter protests continued to reverberate through the UK throughout the summer of 2020 in the wake of the murder of George Floyd.

“I think [the UK] could just take some of these monuments off their plinths and dig a hole in the ground, then bury them up to their waists,” he says. “So you can see them, but you’re looking down on them."William Kentridge, artist

“They put a wooden palisade around the Churchill statue in Parliament,” Kentridge says. “That palisade was saying, for British people, Churchill is the greatest Britain who ever lived. But for millions of Indians who starved because all grain was taken for the British forces during the war, he’s not a hero. Putting that wooden fence around him was great. It said: he’s in there somewhere. You can't see him, but we know of his presence. And it sets it as a question mark, which is when the statue is at its most alive. Removing the statue does not take the question away. Leaving it doesn't solve the question. But that palisade allows for a space in between.”

Kentridge suggests that a reinterpreting, or reframing, of comparable statues may allow the UK to develop a consensus around the country’s history. “I think [the UK] could just take some of these monuments off their plinths and dig a hole in the ground, then bury them up to their waists,” he says. “So you can see them, but you’re looking down on them."

Kentridge acknowledged there is “a dialectic of complications with colonial history and the way it transforms societies.”

“It’s now very central in the agenda,” he says. “The Black Lives Matter movement was a lot to deal with for many in the Western world. In South Africa you must understand the struggle against apartheid has been the ongoing and central question for decades and decades.”

Kentridge's opera at the Barbican opened with The Moment Has Gone, a short film accompanied by a live piano score and an all-male South African chorus, which charts the making of City Deep, Kentridge’s latest animated film, which is premised around the prints and charcoal drawings he routinely makes in his Johannesburg studio.

The opera, originally performed at the Teatro dell’Opera in Rome, is one of a series of performances Kentridge is staging across Europe. At the Paris Opera in March, and then at the Liceu Opera Barcelona in May, Kentridge staged his interpretation of Wozzeck, the first opera by the Austrian composer Alban Berg, and first performed in 1925. Meanwhile, in Lucerne, Switzerland, Kentridge was commissioned by the Lucerne Symphony Orchestra to create a film based on Dmitri Shostakovich's 10th Symphony, titled Oh to Believe in Another World, which premiered on 15 June. In October, Kentridge will return to the Barbican to stage The Centre for the Less Good Idea, a series of six short performances blending dance and live music, and which will be on show alongside his retrospective at the Royal Academy.