What can you do with the art that you own? Well, it rather depends. You are free, if so minded, to destroy an easel painting or portable sculpture. But woe betide those who seek to remove a feature which forms part of a listed building, or a listed statue. These have an elaborate mechanism of protection that can earn the malefactor a criminal record. Thus the unauthorised sale of a listed urn can land you in deep trouble, and yet you could burn an Ingres with impunity. It is a complicated area, demanding caution.

Most of Contested Heritage covers regulatory consent: what you need permission for, what is protected, and what the case law amounts to. Other (short) chapters in Part One focus on the laws governing the changing of street names and the removal of art from churches.

Part Two is about ownership: on what limitations there are surrounding an owner’s right to enjoy their property. Issues such as “the degree of annexation to the land” determine the legal status of buildings and some works of art. A test case in 1902 established that tapestries tacked to a wall of a rented house (Luton Hoo, no less) should not pass from their owner to the landlord when the former died, on the basis that they had become physically attached. These small things can matter greatly.

Some cases are well known, such as that of Antonio Canova’s The Three Graces, which famously reached the courts in 1991, when the duke of Bedford offered it on the market and the Getty Museum sought to acquire it. The High Court wrestled with issues of artistic intention and the details of fixture. The sculpture now divides its time between the Victoria and Albert Museum and the National Gallery of Scotland, having obtained leave to be removed from Woburn Abbey but not from Britain. Withholding an export licence put paid to that. Less well known, but still important in terms of legal precedent, is the recent case known simply as “Dill”. This centres around a pair of 1720s lead urns on stone piers originally from Wrest Park, Bedfordshire.

Like many other Georgian parkland features, they were sold off in the early 20th century and ended up at Idlicote House, Warwickshire. They were listed in 1986, but sold and removed in 2009. Seven years later, the local authority took listed building enforcement action to recover them. Even though not originally at Idlicote House, they had been listed and thus needed consent to be removed. Richard Harwood led the team which challenged this, and the Court of Appeal concluded that the urns were not a “building” in the legal sense; common sense prevailed in this instance, and off they finally went.

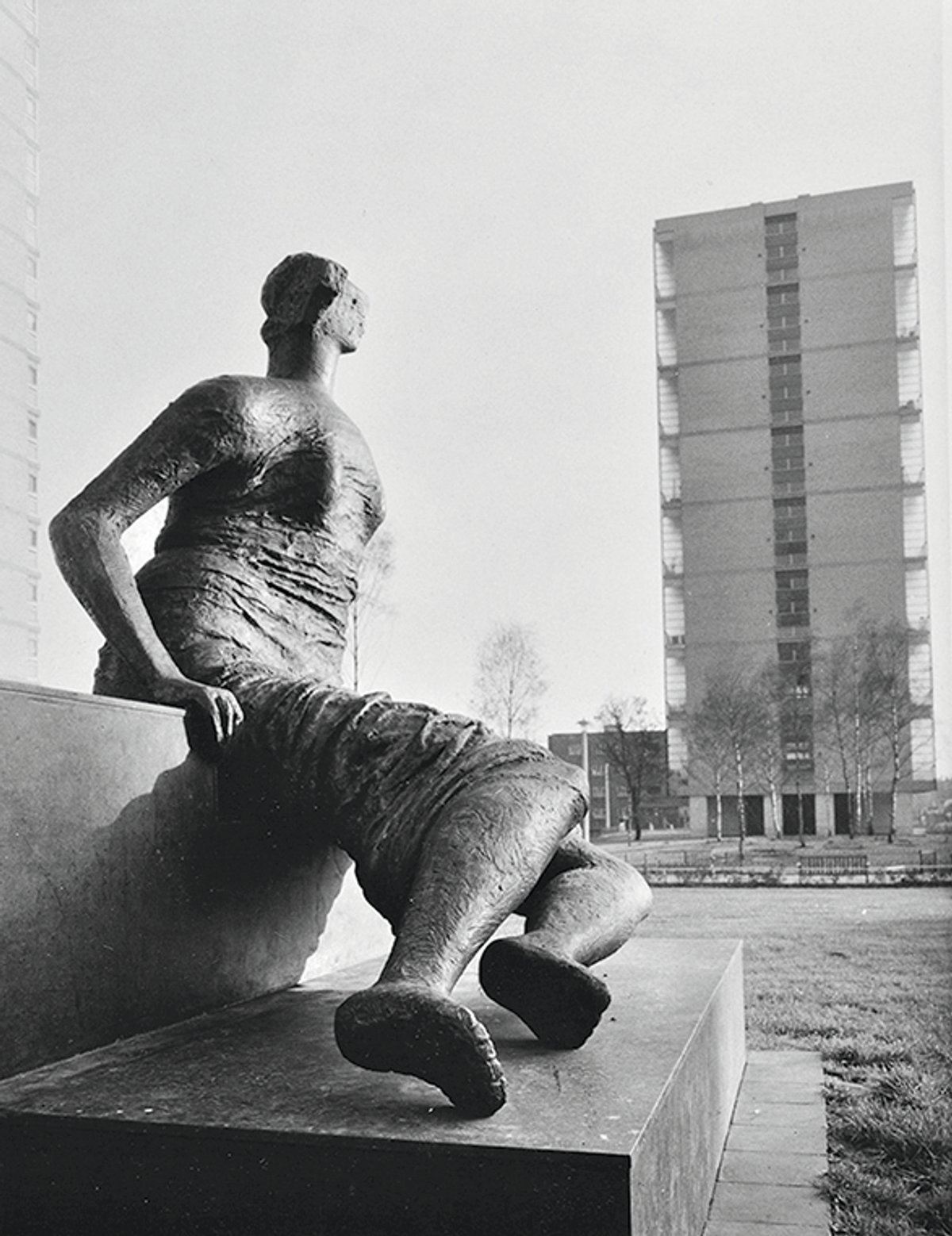

Other cases include Desert Quartet, installed in 1989, a series of giant busts by Elisabeth Frink that still enhance the rear of a shopping centre in Worthing after listing prevented their removal. And Henry Moore’s Draped Seated Woman (1957-58), nicknamed Old Flo, which was moved when the Stifford Estate in east London was demolished in 1997, narrowly avoiding being sold off by Tower Hamlets council; it has now been relocated to Canary Wharf.

The last section, Part Three, covers the most contested item of UK heritage in recent times—John Cassidy’s 1895 statue of Edward Colston in Bristol. There is brief discussion of the UK government’s enshrining of the “retain and explain” position towards disputed statues, now formally set out in planning guidance. This section asks the big questions: is the undeniable historic importance of the listed statue outweighed by its being a “visible representation which is threatening or abusive” as defined by the Public Order Act 1985?

This is art history in action, and the legal context is changing quite fast. It is a good thing, then, that Harwood—a KC (King's Counsel) and one of the leading barristers in the field of heritage planning—has written this brisk but dense guide. It is a legal book, stiff with footnotes, and aimed firmly at the lawyer or the heritage administrator. It is essential reading for all who need a clear and authoritative survey of the issues.

• Richard Harwood, Catherine Dobson and David Sawtell, Contested Heritage: Removing Art from Land and Historic Buildings, Law Brief Publishing, 209pp, £79.99 (pb), published 31 May

• Roger Bowdler is a partner at Montagu Evans, advising owners on historic buildings. He was director of listing at Historic England and writes on funerary art.