Nicole Eisenman became successful as a painter, but the vast range of media and materials she employs is an aspect of her work that the curators of her show at the Whitechapel Gallery are seeking to emphasise. There are sculptures, prints, drawings, murals, paintings and a complex new installation, Maker’s Muck (2022), featuring a giant sculpted figure beside a rotating potter’s wheel, surrounded by maquettes for some of Eisenman’s best-known works.

Maker’s Muck incorporates plaster, silicone, foam, trainers, tin foil, bamboo skewers, wax, dried flowers, crochet and seashells, to mention just a few of the materials listed in the catalogue.

“She is one of the most inventive artists in the world at the moment, and one of the most ambitious artists in terms of how many mediums she works in,” says Mark Godfrey, who curated the exhibition with Monika Bayer-Wermuth.

Even within the medium of painting, Eisenman’s work is extraordinarily diverse, spanning Bruegel-like wimmelbild images with dozens of figures engaged in a variety of activities and some surreal elements, like the enormous 2006 work Progress: Real and Imagined; spongy fantasy heads painted in oil on foam, such as the 2007 work Devil; and contemporary genre scenes of beer gardens and dinners. Some works carry a clear political message, such as The Abolitionists in the Park, a 2022 painting of a protest rally demanding a cut in police funding after the death of George Floyd.

Born in 1965, Eisenman found success in the early 1990s, and the Whitechapel exhibition spans three decades of her career. Earlier works on show include rambunctious graphic drawings, such as Captured Pirates on the Island of Lesbos (1992), a gruesomely funny depiction of warrior-like women cutting the penises off their captives, which challenges conventional portrayals of sexual violence in art. Another 1992 ink drawing, Lesbian Recruitment Booth, shows a queue of women at a stand with a sign bearing the title of the work and the slogan “Try it, you’ll like it.”

“Eisenman used humour in a very raucous way at the beginning to make new kinds of representations of lesbian life,” Godfrey says. “They weren’t that common in contemporary art.” Later works, like Morning Studio (2016), show domestic scenes. “You can see her engagement with lesbian life in New York with queer couples throughout the exhibition, in different, simple ways—like how she might present a pair of people relaxing, how she presents romance,” Godfrey says.

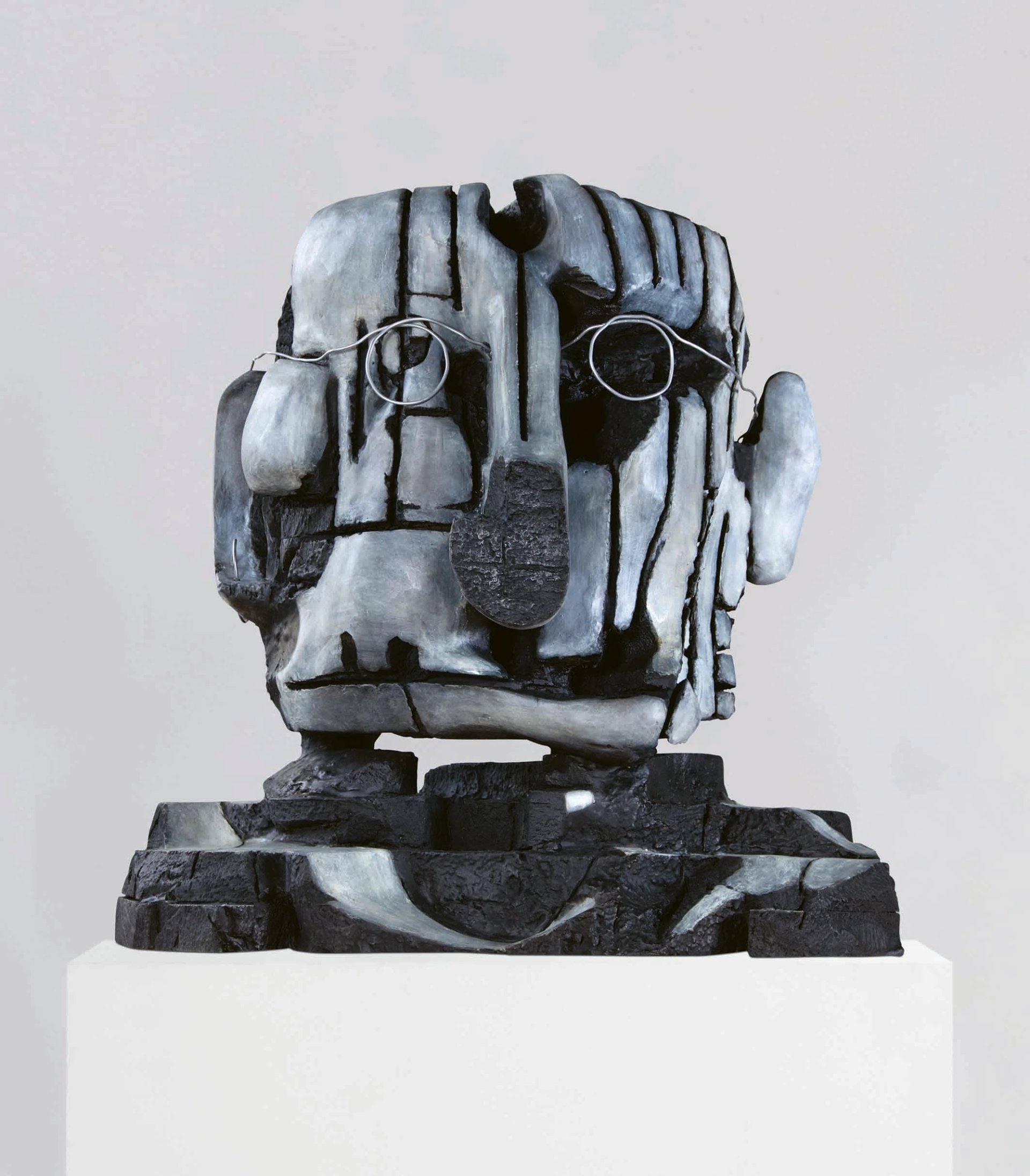

Econ Prof (2019), made from bronze. After early success as a painter, the artist has gone on to employ a range of media Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Transient state

Eisenman’s murals were by definition temporary: she painted ten between 1992 and 2003 on the walls of exhibition spaces, then painted over them when the shows ended. For this exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, she has worked with the artist Ryan McNamara to create an animation of them that will be shown for the first time.

During the early 2000s Eisenman felt that, after a period of success, she had fallen out of favour. Some of the more introspective paintings on show address her response to this perceived fall from grace—with the same dark humour that is apparent throughout her work. In From Success to Obscurity (2004), Obscurity is a blue monster akin to Marvel Comics’ Thing, who is forlornly reading a letter, presumably from Success.

“It shows how productive a moment a dip in confidence or public profile can be for an artist,” Godfrey says. “You can see as you go through the show that that dip was very productive for her in terms of making her think about art and about how she made art. I hope that’s an indication for younger artists that there are great benefits of looking at the long run in terms of their career, and moments when things are very much in vogue and moments when they’re not.”

Eisenman’s influences range from comics and soft porn to Pieter Bruegel the Elder and even Renoir. But a German Expressionist influence stands out, particularly in paintings depicting the hardships of contemporary life, such as the 2008 Coping and the 2009 The Triumph of Poverty.

She has indicated that this might reflect her family history: as Jews persecuted by the Nazis, they were forced to leave Vienna. “I grew up in a family with a sense of nostalgia”, she has said, and “this sense of longing for another time and place comes through in my paintings… I think it’s part of my job as a human on earth to process the sadness of my family.”

• Nicole Eisenman: What Happened, Whitechapel Gallery, until 14 January 2024