Little has changed in the office of the Aboriginal art dealer Tim Klingender since his death in a boating accident near the heads of Sydney Harbour two years ago, aged 59. The loft space overlooking the pale sands and sapphire water of Bondi Beach is still heavy with the objects of his work. Shelves groan with books on Indigenous art, every inch of wall is hung with paintings, cabinets are stuffed with artefacts, and the big wooden desk is piled with Sotheby’s catalogues, the fruits of 25 years working with the auction house.

Klingender’s widow, Skye McCardle-Klingender, has spent the past two years working through the uncollated life that he left behind there, and is now looking to continue his legacy with an auction at Sotheby’s New York on 20 May. “The business continues, even if Tim doesn’t,” she says.

“He thought these painters should be acknowledged and respected like Picasso, or anyone else"Skye McCardle-Klingender

As Sotheby’s in-house expert for Indigenous art, Klingender organised auctions of works by leading contemporary and historical artists. He drove the market from when Sotheby’s set up its Aboriginal art department in Melbourne in 1997, through the spike in interest in Aboriginal art in the mid 2000s, and eventually held several record-breaking auctions in New York in the years before his passing. “He created the market for Aboriginal art internationally,” McCardle-Klingender says. “He thought these painters should be acknowledged and respected like Picasso, or anyone else.”

To put together the multi-owner auction, which includes pieces from Klingender's personal collection, she is working with Wally Caruana, the inaugural curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art at the National Gallery of Australia from 1984 to 2001.

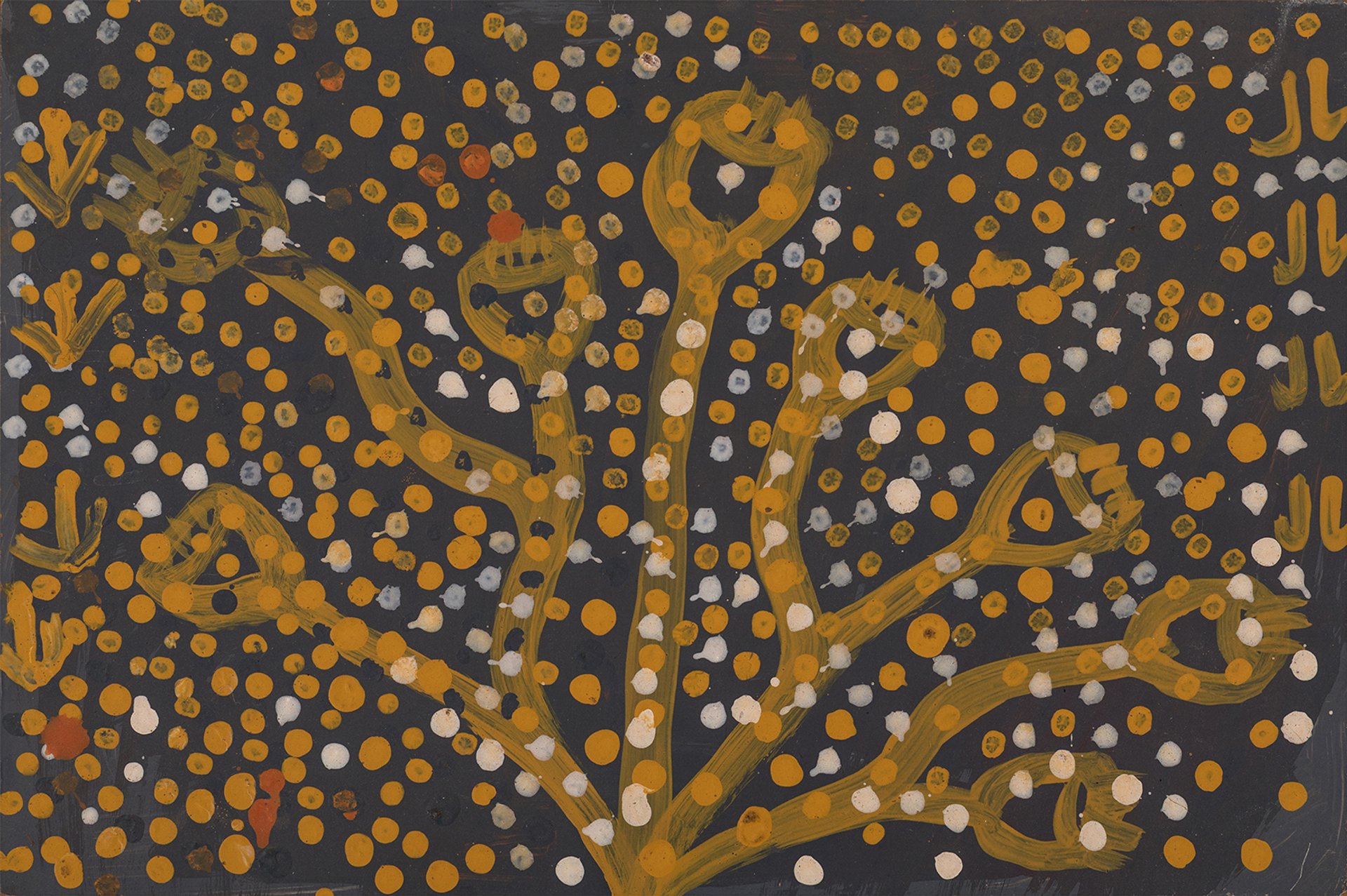

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Untitled (Intekw) (1990)

Courtesy of Sotheby's

The sale's 65 lots include five works by Emily Kam Kngwarray, one of the most famous and commercially successful Aboriginal artists. Hailing from Alhalkere Country in central Australia, she only began painting in her 70s, but drew from a lifetime of practice in traditional ephemeral art to produce rich depictions of her culture and history, also incorporating colours from outside the palette of her country. “It’s a lovely range that spans her career, including a couple of very large, atmospheric pieces,” Caruana says of the sale's Kam Kngwarray works, the largest of which are expected to fetch up to $700,000. “There’s also two wonderful, very small boards which she painted in the middle of 1990—incredibly intimate works which weren’t painted for the market," Caruana adds. He hopes for up to $50,000 for these smaller, untitled pieces.

Other big names in the auction include Ginger Riley Munduwalawala—a master of colour—whose 1992 painting Limmen Bright Country is estimated between $30,000 and $50,000, as well as Rover Thomas and Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri. Two works by the prominent contemporary artist Richard Bell are offered: Strike (2022) and Where is the Outrage (2023), which could each sell for $70,000.

Ethical dealing

Trade in Aboriginal art has a long history of exploitation, and Klingender was known for his "unwavering commitment to Aboriginal-owned and governed art centres as the most ethical and sustainable model for the sector", says Skye O’Meara, the chief executive of the APY Art Centre Collective, a group of Indigenous owned and governed art centres. Artists have historically been deprived of agency by profiteering traders, often called carpetbaggers, who buy up large quantities of artworks at low prices and later sell them off for maximum profit, with no involvement or revenue for the artists themselves.

Community-run art centres developed across the country to combat this, providing materials, studios and an institutional home for artists, especially those working in remote areas. They allow artists to sell their work, either through the centres’ own galleries or third-party dealers, providing income and employment for artists and artworkers.

Art centres also provide reliable provenance through the certificates that they issue, which often include descriptions or context from the artists themselves. According to O’Meara, Klingender “understood that Indigenous-owned art centres are the economic engine rooms of remote Aboriginal communities—driven by Elders to serve Aboriginal families and uphold cultural authority. These centres are not just art making studios, but vital social enterprises with the power to move the needle on Indigenous disadvantage.”

The auctions Klingender organised from 2018 in New York were the highpoint of his advocacy. While the global art market faces headwinds under today’s economic uncertainties, this auction be a bellwether for the future of the Indigenous art market, and for Klingender’s legacy. Will the works on offer this year continue to keep up in the middle of New York’s peak season?