In an eerie replay of Soviet-era repression, Russia’s crackdown on artists and free expression appears to be escalating. A growing number of artists, curators and cultural figures have been detained in recent months in cases that seem simultaneously random and targeted, creating a culture of fear for those who have not yet left the country.

Alisa Gorshenina, an artist from Nizhny Tagil, a military-industrial city near Yekaterinburg in the Urals region, who used images of regional languages and folklore to speak out against Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, was arrested for ten days in April for using “extremist symbols”. She was released, but fined 145,000 rubles ($1,800) on charges of “discrediting the military” and “LGBT propaganda”, a serious accusation since the “international LGBT movement” was branded a terrorist organisation by the Kremlin in 2024.

In 2024, an embroidery workshop led by Gorshenina at the Yeltsin Center, a cultural venue founded in Yekaterinburg, the hometown of Russia’s first president Boris Yeltsin, was postponed due to denunciations by pro-war activists. “Every day, there seem to be fewer and fewer opportunities,” Gorshenina told OVD-Info, a human rights publication, at the time. “I see and understand this: everything points to the fact that I should leave, but I want to make that choice for myself.”

Meanwhile, a criminal case was launched in March in Perm against Nailya Allakhverdiyeva, an artist and curator who had been the director of the PERMM contemporary art museum. She is accused of “offending the feelings of religious believers” for works she displayed at the museum last year, a draconian law passed after Pussy Riot members were imprisoned for their “punk prayer” at Moscow’s Christ the Saviour Cathedral in 2012. The cultural impresario Marat Guelman, who has been in exile since 2014, founded the museum. He has been labelled a foreign agent and terrorist in Russia. Searches and detentions of artists have taken place across the country since 2024 in connection with a case against him.

“Russia is currently at war, and until war is over, the government will do everything to control culture and artists,” Polina Sadovskaya, an independent consultant and the former advocacy and Eurasia director for PEN America, tells The Art Newspaper. Sadovskaya has been tracking the crackdown, as well as artists’ efforts to escape control in a “very limited and narrowing” space. “Even now, they keep making art in Russia and display it on still available platforms.”

However, their art is becoming ever harder to see through the thicket of officially promoted cultural support for the war. Sculptures of the Russian fascist philosopher Aleksandr Dugin, whose ideas have motivated Putin’s policies, and his daughter Daria, who was killed by a car bomb in 2022, were recently displayed in a space at Zaryadye. The park next to Red Square and the Kremlin, commissioned by Putin and designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, creators of New York’s High Line, has been turned into a propaganda art venue.

Return to ‘traditional’ values

In April, Aleksandr Bastrykin, the head of Russia’s Investigative Committee, the equivalent of the FBI, announced that he is creating a “council on culture” as part of the agency to create “cultural works aimed at young people and promoting the formation of patriotism, an active civic position, and traditional spiritual and moral values”.

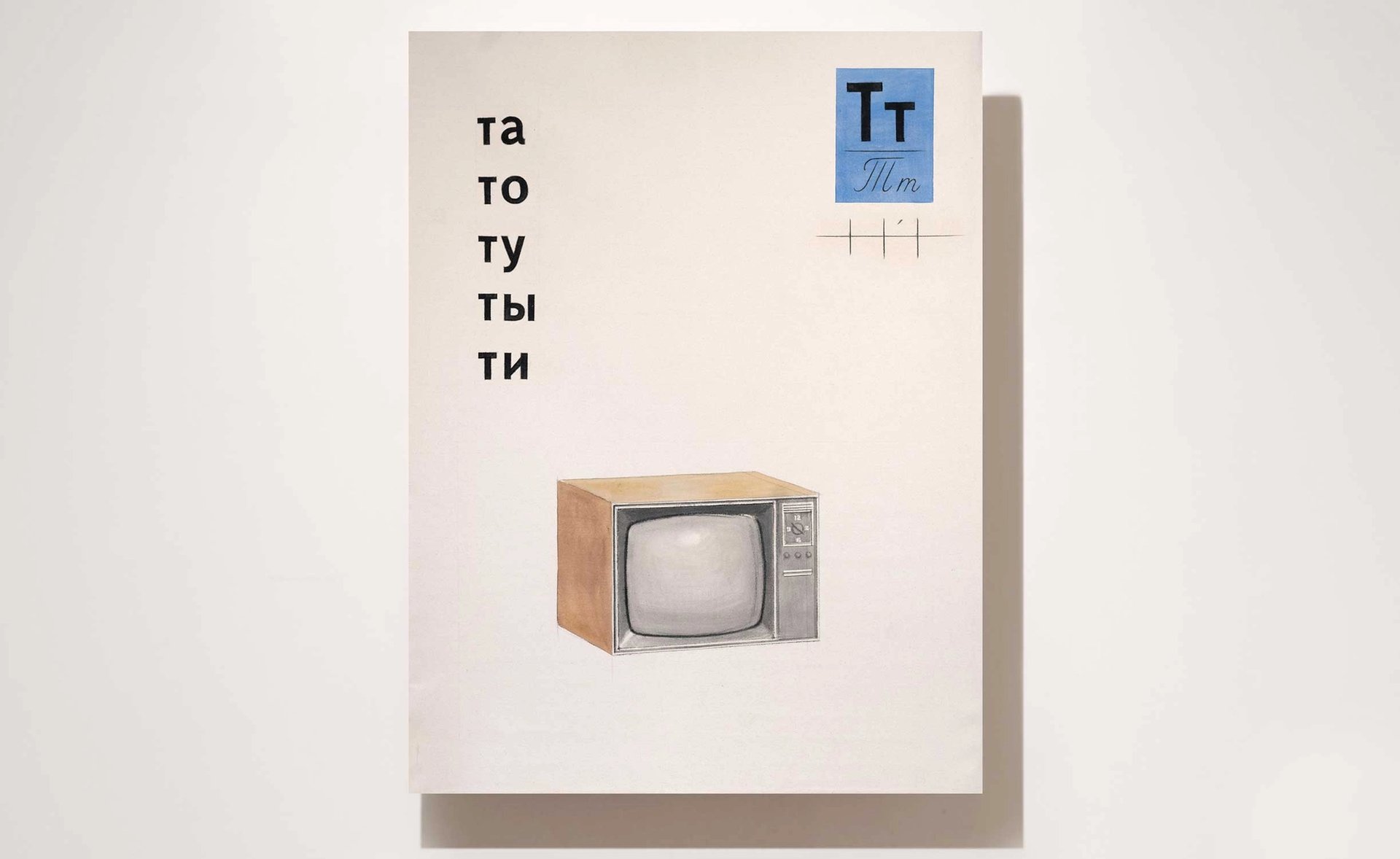

Pavel Otdelnov’s Primer (2024) recalls the fear he experienced during his Soviet childhood

Courtesy Pavel Otdelnov

Another official has been tasked with creating a “Russian visual style” for all state institutions. This “new Russian style” will be created “based on traditional values and the cultural code of Russia”.

Pavel Otdelnov, a Russian contemporary artist in exile, maintains contact with artists in Russia, some of whom are still able to work and travel abroad. He tells The Art Newspaper that new art within Russia often gets little publicity to protect artists, who must now also contend with informers. “I was saddened to learn that there are people on the art scene who gather information about their colleagues and write denunciations,” he says. “Fortunately, this still occurs rarely. But the very fact that it has become possible says a lot about what is happening now.”

Otdelnov is taking part in a group show titled No. The Exhibition in Berlin (until 6 July), curated by Meduza, an independent Russian news site based in Latvia, which features both Russia-based and exiled artists. He recreated a Soviet ABC book, drawing on the sense of fear in his childhood in 1986, when he was “most afraid of war, death in a bomb shelter and, of course, radiation”, because of the Chernobyl disaster. “I think that for an artist from Russia it is especially important to understand the nature of the ongoing catastrophe and to find its roots.”