Sebastião Salgado, the Brazilian photographer regarded as one of the greatest documentarians of his generation, has died at the age of 81. Salgado’s death was confirmed on 23 May by Instituto Terra, the conservation body he founded with his wife and collaborator, Lélia Wanick. In a statement, the photo agency Magnum said it was “deeply saddened by the passing of Sebastião Salgado, an extraordinary photographer, photojournalist and member of the co-operative from 1979 to 1994.”

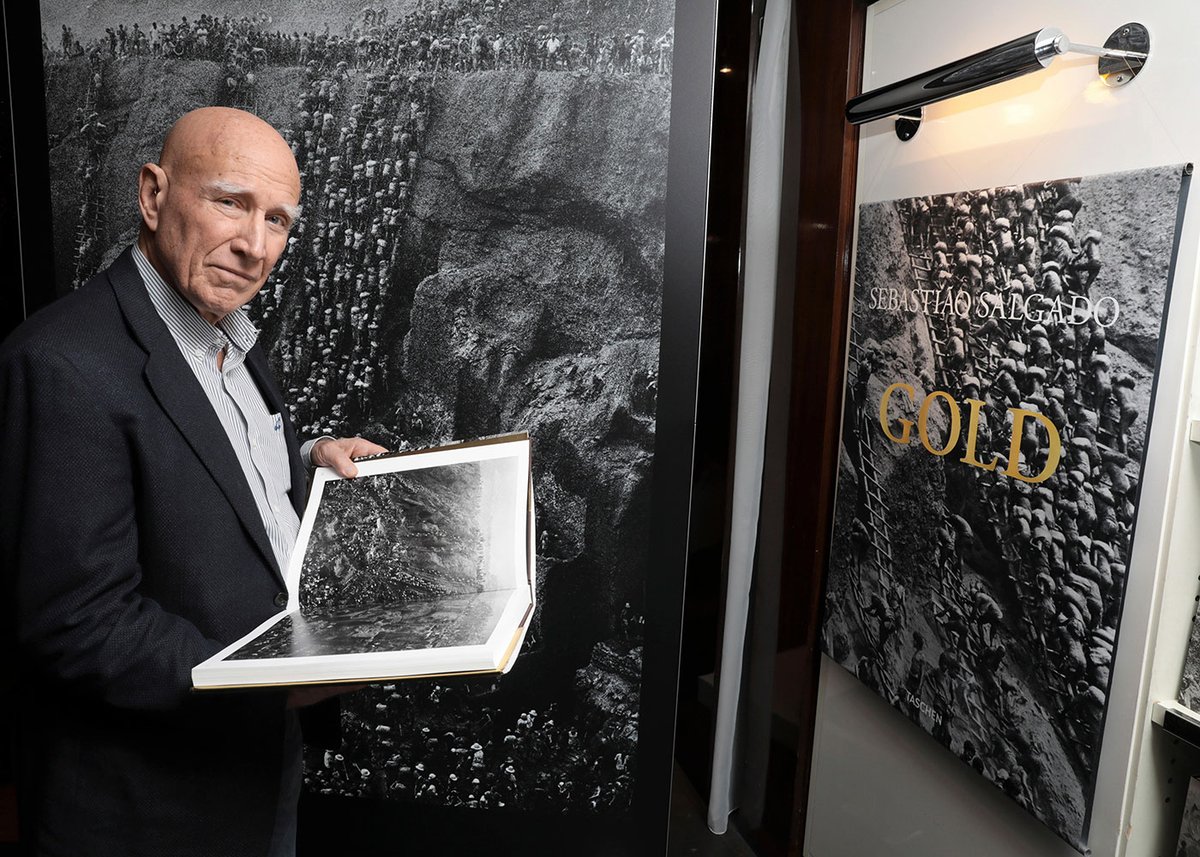

Salgado will be remembered primarily for series such as Workers (1993), Exodus (2000), Genesis (2013) and Amazônia (2021). Each body of work captures people in extremis in dramatically panoramic settings. But he is perhaps best known for Gold (2019), in which he photographed more than 50,000 miners teetering on roughly assembled ladders and churning through mud and stone in the vast pit of Serra Pelada—the world’s largest open-pit gold mine in the northern Brazilian state of Pará. Evoking the legend of El Dorado, Salgado captured, in burnished black-and-white, the appalling conditions these migrant workers endured in their search for the precious metal.

The demands of Salgado’s photographic practice were chronicled in the Oscar-nominated documentary The Salt of the Earth (2014), directed by Wim Wenders and his son Juliano Ribeiro Salgado. Speaking to Wenders in the film, Salgado says of the human race: “We are a ferocious animal. We humans are terrible animals.”

In the film, he recalls the task of trying to photograph the enormity—visually and emotionally—of what he found at Serra Pelada. “When I reached the edge of that enormous hole,” he said, “in a split second, I saw, unfolding before me, the history of mankind, the building of the pyramids, the Tower of Babel, the mines of King Solomon.”

Born in 1944 to a cattle rancher in Aimorés in Brazil’s southeastern state of Minas Gerais, Salgado initially trained and worked as an economist before taking up photography in the early 1970s after travelling to Africa with the World Bank. He quit his job as the chief economist for the International Coffee Organisation to pursue professional photography, finding assignments as a roving documentary and conflict photographer with agencies including Sygma, Gamma and, later, Magnum. He photographed the Zone Turquoise refugee camp in Rwanda, the droughts of sub-Saharan Africa, the Bosnian civil war and Afghanistan under Taliban rule in the years before 2001.

Salgado was renowned for his immense technical prowess, using state-of-the-art equipment in some of the most remote places in the world. Yet his work was also steeped in the history of photography. He fused the traditions of social documentary and humanist photography, associated with figures such as Dorothea Lange and W. Eugene Smith, with a modernist interpretation of the pictorialist tradition of Ansel Adams and Edward Weston—a photographic movement aligned to Group f/64 that aimed to elevate nature and landscape photography to the status of fine art by focusing on tonality and composition, often manipulating saturation, exposure and focus, and deploying highly technical printing techniques to achieve a painterly beauty.

Salgado wove each of these influences into a unified style. Yet he was also a photographer of immense determination and commitment—one unafraid to work in the most taxing and, often, hazardous environments. Writing in the foreword to Exodus, the photographer recalled that, after returning from covering the Rwandan civil war, he “started to be attacked by [his] own Staphylococcus”—the toll of witnessing extreme human suffering led to both a physical and mental breakdown, resulting in a bacterial infection that almost killed him.

“I saw in Rwanda total brutality,” he wrote. “I saw deaths by thousands every day. I lost my faith in our species. I didn’t believe it was possible for us to live any longer.”

His most recent series, Amazônia (2021), brought together decades of images of Indigenous communities who live deep in the Amazon rainforest, with little contact with the outside world. The work demonstrates engagement, collaboration and mutual understanding with tribal groups who have little concept of globalised society beyond the enveloping confines of the largest rainforest on Earth. The intuitive skills required to navigate this profound cultural gap are built into the frame of each photograph.

But his work was not without controversy. Opponents have accused him of romanticising poverty and aestheticising Indigenous customs for the purposes of the gallery wall. In an interview with The Guardian newspaper, João Paulo Barreto, an anthropologist from Brazil’s Yé’pá Mahsã (or Tukano) ethnic group, accused Salgado of using “the optics of romanticisation”, noting that Salgado was happy to publish photographs of naked children from Indigenous communities. Salgado countered that his images testified, in monumental form, to the inherent value of human life.

In later years, Salgado openly aligned his work with the principles of environmental activism. In 1994, he founded his own photo agency, Amazonas Images, with Lélia, an author and environmentalist who co-created many of his photobooks. Shortly after, in 1998, he and Lélia established Instituto Terra to restore damaged rainforest in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil. The organisation is credited with the reforestation of thousands of acres of land.

Salgado used his photographs to make profound political points, steeped in the economic learnings of his early career. In Exodus, he wrote: “The dominant ideologies of the twentieth century—communism and capitalism—have largely failed us. Globalisation is presented to us as a reality, but not as a solution. Even freedom cannot alone address our problems without being tempered by responsibility, order, awareness. In its rawest form, individualism remains a prescription for catastrophe. We have to create a new regimen of coexistence.”

Sebastião Ribeiro Salgado Júnior; born Aimorés, Minas Gerais, Brazil 8 February 1944; married 1967 Lélia Wanick (two sons); died Paris 23 May 2025