A selection of Korea's most exciting contemporary artists have been selected for this year's Korean Artists Today, a long-term project which will see a cohort of artists chosen each year for their potential to make it on the global stage. See the full list here.

Choi Goen makes sculpture out of the discarded everyday objects—household appliances and industrial scrap—that form the infrastructure of our daily lives. “My work always begins with discovering a material,” she says. “When I come across something that sparks a desire to change or reimagine it, that moment becomes the starting point of a piece—the more familiar the material is, the more naturally I can imagine it differently.”

For her 2019 installation White Home Yard at Seoul Museum of Art, Choi created 14 abstract sculptures from the outer shells of fridges and air conditioners; and her winning commission for the 2024 Artist Award at Frieze Seoul continued her interest in transforming what society throws out. Installed at the entrance to the fair, White Home Wall: Welcome was made from around 60 air conditioning units collected from across Seoul. These were suspended in a half circle formation, arranged according to their year of production, from 1992 to 2008. “I imagined it as a kind of eclipse, revealing the hidden exteriors of domestic infrastructure that are usually invisible,” Choi says. “It felt like a monument to consumption, like the exhumed bodies of products on display just before their afterlife.”

Trophy (2022), in Choi’s solo show Cornering at Amado Art Space, Seoul

Photo: CJY ART STUDIO; courtesy the artist

When a familiar material is reassembled in an unfamiliar way, it invites viewers to re-engage with their own habits of seeing

Choi feels it is always important to work with materials that have had a past life and bear the traces of their previous function. “There’s something moving about the deep white of a sun-faded air conditioner,” she says. “Those ‘differences’ are like geological layers—formed by specific periods, production environments and economic conditions. My work often begins from that kind of material specificity, and builds out from there as a sculptural inquiry.” This concern with recentring what she describes as “things that have been pushed to the edges” is not so much about notions of recycling as it is feeding into her wider socio-political interest in urban systems, industrial structures, and cycles of production and consumption.

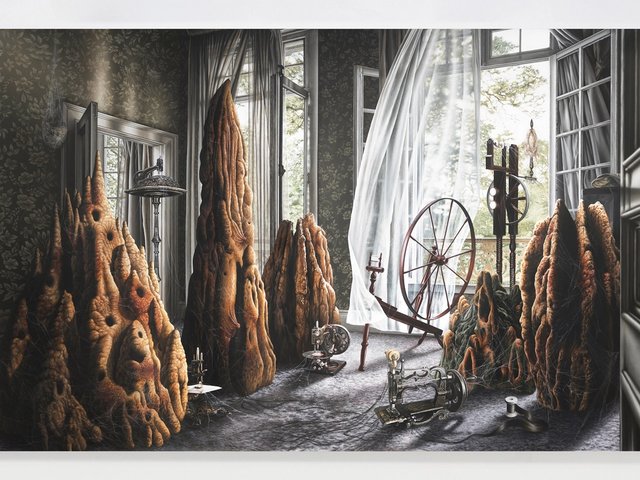

White Home Yard (2019), in The Unstable Objects at Seoul Museum of Art

Photo: Nothing Studio; courtesy the artist

Just as Choi’s materials came into existence through industrial manufacture, it is significant to both the form and meaning of the final works that they are produced collaboratively in a factory rather than a studio setting. “The materials I use are physically demanding so my work often happens outside the studio, in factories on the outskirts of the city,” she says. “I enjoy visiting these sites and watching how things are made, especially when they involve outdated materials or processes no longer found in the urban centre.”

But although she cuts, bends and reassembles elements of urban infrastructure in ways that disrupt their function, Choi’s sculpture is not so much a critique of the rigidity of our social and economic systems as a recognition of how she—and all of us—rely upon them. “I live within the same ecology,” she says. “I work with materials that move through cycles of rapid production, consumption and disposal and I’m part of that system, too. I intervene in that flow and manipulate and reconfigure these objects to explore how I exist within those structures, both physically and conceptually. When a familiar material is reassembled in an unfamiliar way, it invites viewers to re-engage with their own habits of seeing.”

Choi Goen

Photo: snakepool; courtesy the artist

Recently, however, Choi has been moving away from heavy materials and large-scale installations to make work that is more hands-on. “I’ve been spending more time drawing—trying to reconnect with a more intuitive rhythm,” she says. “There’s something about that process that feels lighter, more direct. I’m not sure where it will lead yet, but I’m giving myself space to return to sculpture in a way that feels slower and more personal.”