A selection of Korea's most exciting contemporary artists have been selected for this year's Korean Artists Today, a long-term project which will see a cohort of artists chosen each year for their potential to make it on the global stage. See the full list here.

Sun Woo was born in Seoul but as a child moved to a small town in Ontario, Canada where, in an environment that was both unfamiliar and often hostile, she struggled to achieve a sense of belonging. She remembers spending much of her time sitting in front of the computer, with online chats and social media platforms the only means to keep in contact with family and friends at home. “This ongoing sensation of living in transit, straddling two cultures in the midst of a rapidly changing technological landscape, sparked my interest in things that exist in the in-between,” she says. “Keeping up with new technologies became a means of survival and belonging—digital spaces often felt more like home than my physical surroundings—yet at the same time they never satisfied my urge to belong.”

Sun Woo was born in 1994 in Seoul

Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac

I’m interested in how the body navigates unfamiliar territory

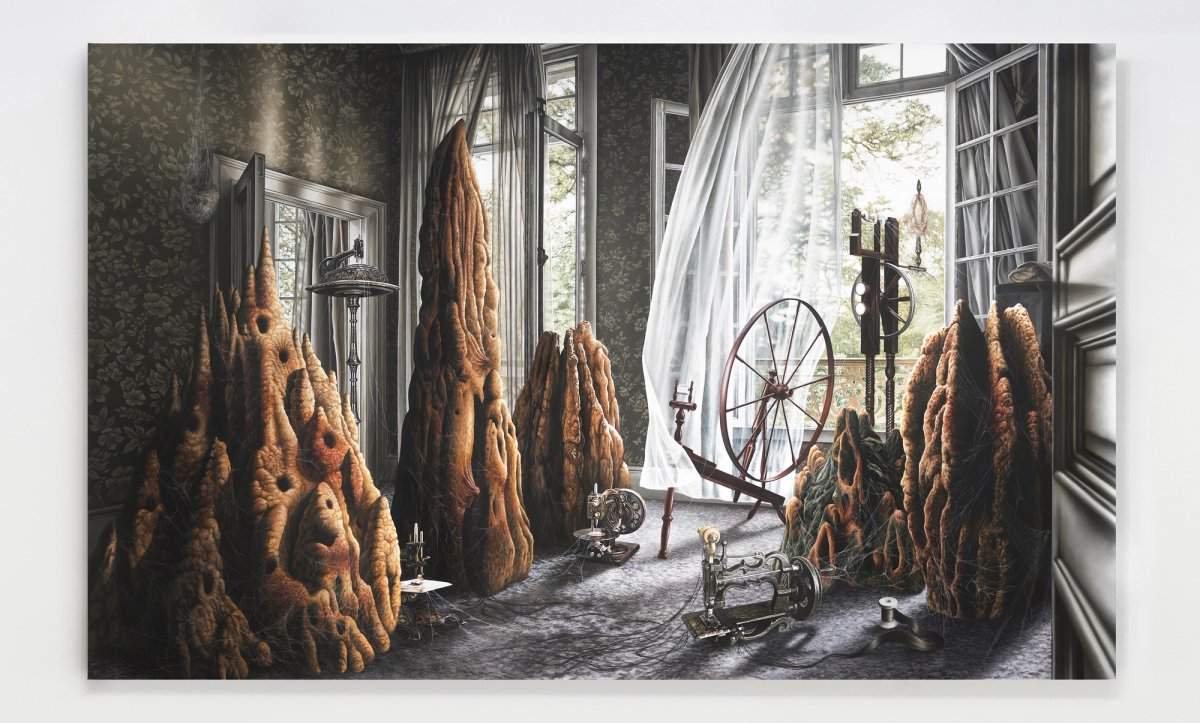

After completing a BA in fine art at Columbia University in New York in 2017, Sun returned to Seoul where she still lives. But these early memories of displacement and dislocation, along with a deep and ambivalent relationship with technology, have remained with her and continue to inform her practice. “Displacement and dislocation aren’t just metaphors, they’re lived realities,” she says. These feelings of fragmentation and vulnerability are reflected in Sun’s paintings, sculpture and installations, which present eerie scenarios in which bodily elements such as flesh, bones and hair merge with mechanical devices or form disturbing relationships with their surroundings. Often these works reference female exploitation and labour, as in the painting Weaver’s Room (2024), where giant termite mounds with the texture of human skin loom incongruously within a domestic space, tangled in webs of hair that spill out from vintage sewing machines.

“I’m particularly interested in how the body navigates unfamiliar territory, whether cultural, technological or emotional, and how that process can be simultaneously alienating and transformative,” she says, adding that she wants her work to “reflect the lived realities of how bodies, especially those that are navigating cultural, social or historical rifts like diaspora, hybridity or maginalisation, are constantly being shaped—or misshaped—by forces beyond their control”.

Sun’s early engagement with technology directly informs the way in which she uses both digital and analogue processes to make her work. Much of her imagery is gathered online using search machines, algorithms and, more recently, generative AI tools. “Once I’ve gathered these digital images, I collage them in Photoshop, recontextualising them by cutting, warping and fusing them with images of my own body, as well as that of my mother and other Asian women, together with objects, landscapes and devices,” she says. These preliminary composite “sketches” are then projected on to canvas and meticulously painted by Sun in oils and acrylic using both airbrushing and hand painting. A similar hybrid approach underlies her sculpture and installations, which are also conceived digitally and then realised physically using a variety of materials ranging from hand-worked bronze and wood to 3D-printed resin.

Sun sees her use of analogue techniques as “a way of resisting the ephemeral, often weightless nature of the contemporary condition—of slowing things down. It’s important to me that my own physical presence becomes part of their final form, capturing a tension between the immediacy of digital creation and the slower, more deliberate processes of traditional, gestural artmaking.”

Recently Sun has been immersing herself still further in the treatment and representation of female bodies in South Korean culture and beyond. “With my new oil paintings and sculptures I’m looking into reproductive technologies such as egg freezing, and the caregiving roles that society conflates with femininity” she says. “In South Korea there’s been a steep drop in the birthrate, as more women of my age are rejecting gendered domestic labour, so I’m thinking about how society and technology have marginalised certain female bodies and what the future will look like.”

Sun’s sculpture Portal (2024), which incorporates synthetic hair and a vintage Korean bucket

Photo: © Gallery Vacancy