In his studio on Lake Ammersee in Upper Bavaria, the 87-year-old Georg Baselitz spreads his canvases out on the floor, a way of working he has used for years. On them, he paints full body figures, often two side by side but sometimes a single body, alone and lost in space.

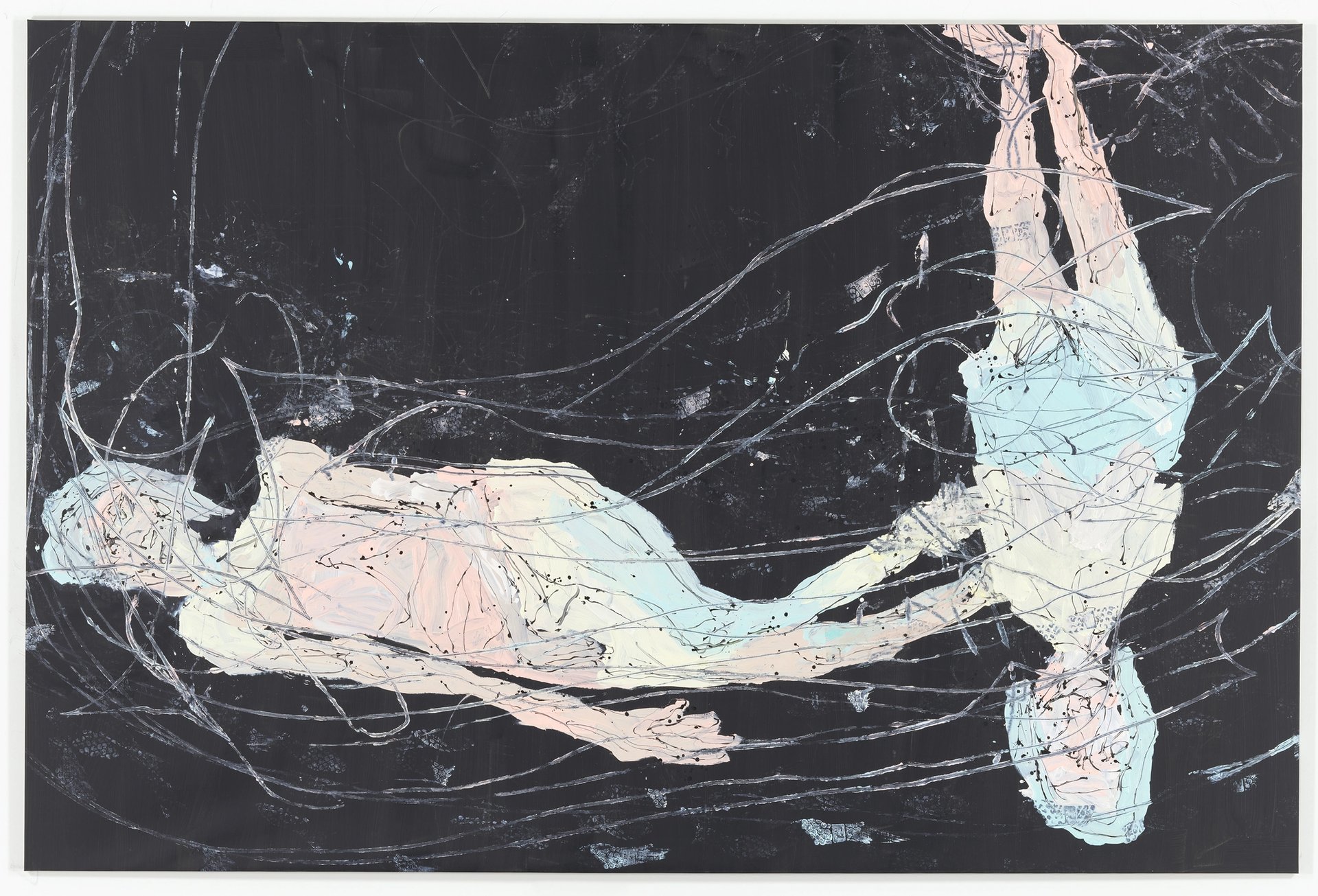

The next stage, now presented for the first time, is new. Baselitz marks the canvas’s surface with the swirling parallel tracks of his wheelchair. With his walking aid, he tap-tap-taps more circular daubs of paint along the edges of the picture plane. As the artist tracks these gyrating lines around and through the human figures on the canvases—depictions of his wife, Elke, and sometimes the two of them alongside one another—we get the anatomical impression of muscles and veins within their torsos.

The 22 large-format paintings made using this inventive approach (all are over three metres wide), as well as 14 ink-on-paper drawings and the artist’s first sculptural work in over ten years make up Baselitz’s exhibition at Thaddaeus Ropac in Pantin, Paris (until 26 July). The exhibition’s curious title, Ein Bein von Manet aus Paris (or ‘A leg by Manet from Paris’), references Baselitz’s interest in anatomy and limbs, especially hands and feet, as well as the tradition of 19th-century Parisian painting. “I have been a little satirical with the title,” Baselitz tells The Art Newspaper, “because Manet’s realism has a habit of only getting as far as the hem of his skirts. As soon as feet start showing up, they’re almost always in the wrong place.”

Enduring evocation

Baselitz met Elke Kretzschmar, his future wife, in 1958 while they were both students at the Hochschule der Künste in West Berlin. She became the artist’s most enduring subject. Baselitz likes his “feet in the wrong place” and, in his famed inverted portraits, in which he formats the picture upside down, Baselitz seeks not to “illustrate Elke” but to “remove her”, he says. Despite his best efforts, however, “she comes into the process” whether he wills it or not.

Georg Baselitz, Traumflug sex, 2025

© Georg Baelitz. Photos: Jochen Littkemann. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery

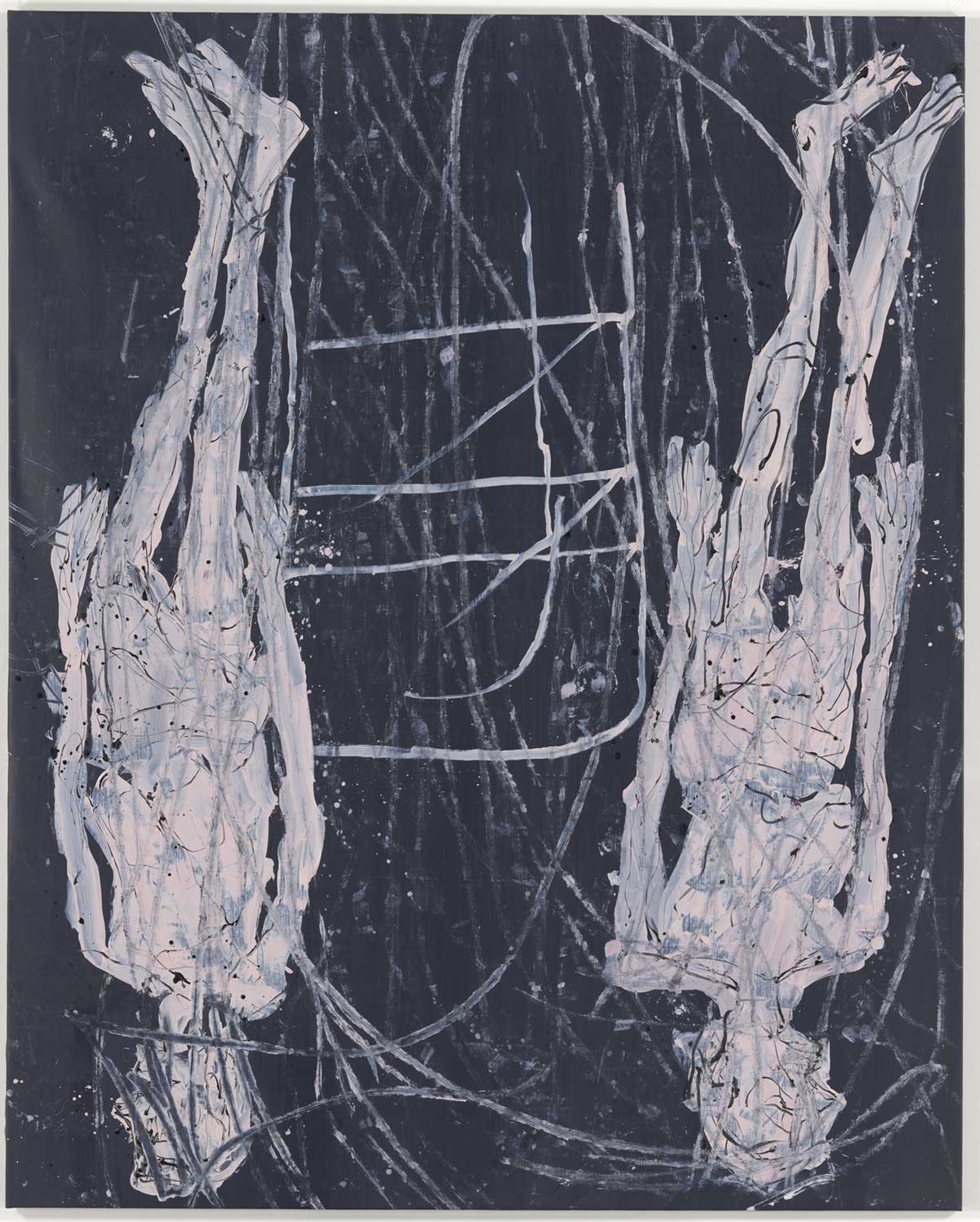

In these new works, the artist is once again struggling with what he calls “the conventions of the genre and the subject itself in order to make something new”. While the technique of using a wheelchair might represent a creative departure for Baselitz, there is something carried over from his early double portraits with Elke, such as Schlafzimmer (bedroom) (1975), in which the nude couple sit side by side surrounded on all sides by wildly gestural marks of paint.

Georg Baselitz's Indigene Kunst von damals (indigenous art from that time) (2025)

© the artist. Photo by Jochen Littkemann; courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac

The skeletal bodies and the palette in the new works are far more diminished than in those joyously colourful double portraits, as they lie flat with arms placed by their sides like mummies or sepulchred saints. When asked whether he saw these new works as a continuation of his decades-long practice or something radically different, Baselitz stresses how “there’s an origin of painting, of course, whether that’s to be found in caves or catacombs”, but in that case, as in his own work, “it’s just how things unfold”. It is clear that Baselitz believes he has something left to say, not only on the history of painting from the cave wall to the salon, but on his own work, which has always been interested in the fallibility of the body in an uncertain world.

A body-machine

After visiting Baselitz’s studio in Germany, Bernard Blistène, the French curator who is a friend of the artist and has written the accompanying catalogue essay for the show, recalled earlier painters who, lived with similar physical disabilities and “in the face of constraint, had invented new tools, until they became an equipped body, so sometimes a body-machine”. Above all, we might think about Henri Matisse’s elongated cane, in which the French master would make marks on the wall of his studio as he convalesced in bed. Hans Hartung, another reference point for Baselitz, also became a wheelchair user after losing a leg while serving in the French Foreign Legion during the Second World War and was pushed around by an assistant in his Antibes studio while he worked in front of his canvas.

In his new exhibition, Baselitz joins this roll call of late-in-life innovators who refuse to allow their indispositions to call time on their creative practice. “I’ve always assumed that my painting is something that takes place inside the head,” Baselitz reflects. “If you need to keep painting, or if you want to keep painting, then you need to expect there to be handicaps as you get older, simple as that, and to be very inventive about how to be able to do it regardless.”

The artist’s restlessness is inspiring, but for Baselitz it is merely a continuation of his extensive work on the contortions of the body that came before. “You could also just say,” he concludes, “where there’s a will, there’s a way”.