Apocalyptic images of bottom trawling, an industrialised form of ocean fishing involving dragging a vast weighted chain with attached net across the seabed, form the most memorable sequences in the new Attenborough documentary, Ocean. Steel teeth rip up the ocean floor, the grim contraption violently hoovering up everything in its path. The result, a bleak colourless ruinscape, could not contrast more with what has been destroyed, an untouched Technicolor world of teeming abundance and variety. It is like viewing the garden of Eden after a nuclear winter, says one interviewee in Ocean.

Bottom trawling emits more greenhouse gases globally than aviation, through the release of “blue carbon”, destroys marine life and habitats indiscriminately, all for the sake of a few scallops—three quarters of what is hauled in is thrown back, dead. “Surely you would think such an activity is illegal,” Attenborough says, pointing out that not only is it legal, but also state subsidised, part of the $20bn spent every year supporting the overfishing that has brought the world’s oceans to the brink of collapse. Ocean is not a wildlife documentary, but rather an activist film about the environmental damage caused by industrialised fishing, and what policymakers must to do avoid total collapse of ocean life, which would mean certain death for the rest of the planet.

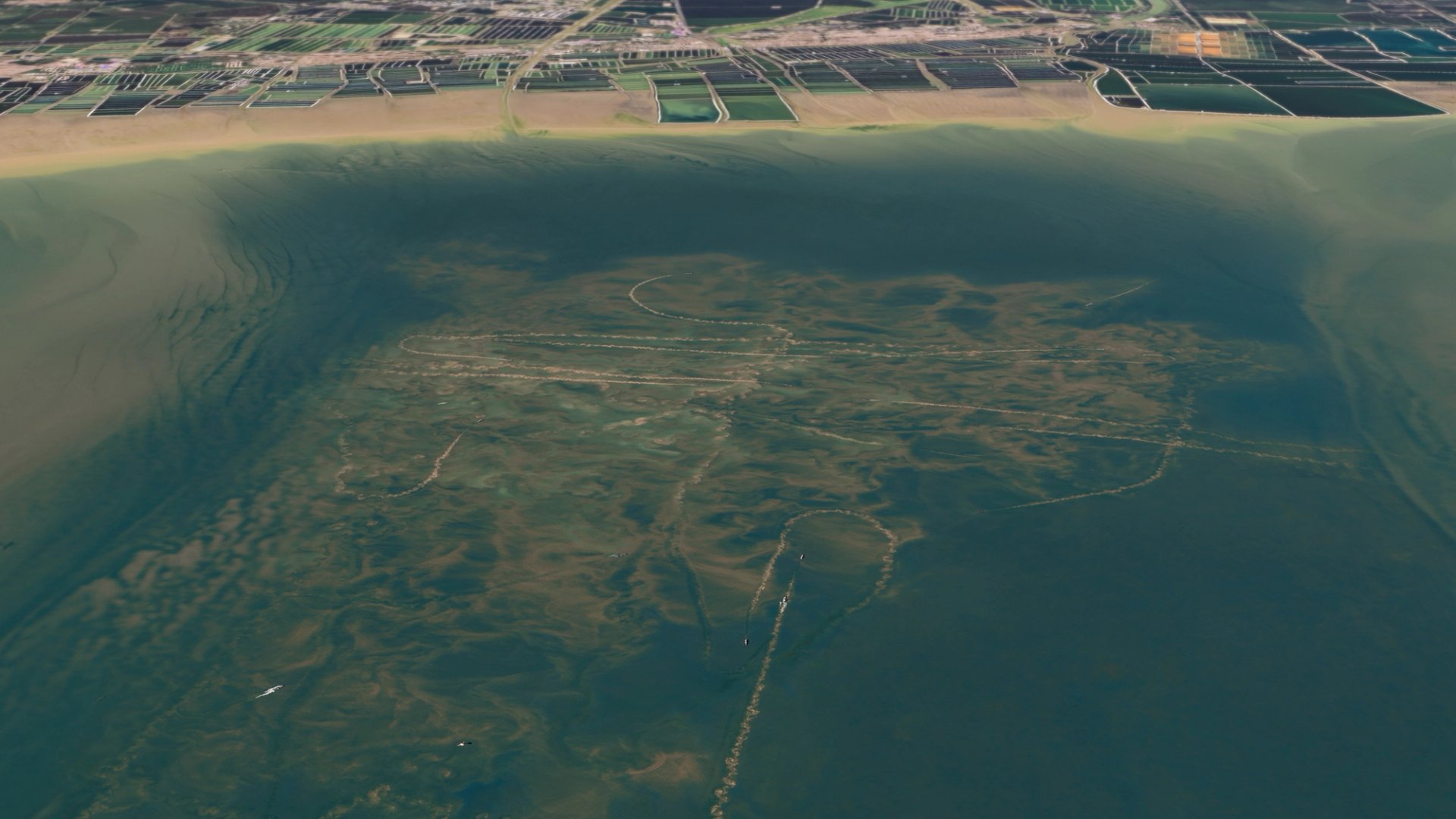

Trawling seen from above in Ocean © SilverbackFilms and Open Planet Studios/Toby Nowlan

High stakes on the high seas

Ocean explicitly targets delegates attending the 2025 United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC) taking place this week in Nice. Never has so much money been spent on a film made for so few, but then never have the stakes been higher. Attenborough addresses the conference directly, repeating the demands for fully protected marine reserves covering 30% of the world’s oceans, and an end to damaging fishing methods, and reminding delegates that the future of humanity depends on the decisions they make.

You cannot miss the power of images in putting this message across. The violent sequences of bottom trawling, and the horrifying images of factory ships scouring the Antarctic, destroying entire marine ecosystems to make pet food, are profoundly disturbing. Against these horrors, Attenborough poses a compelling message of hope. It is now proven that if we leave them alone, the oceans will regenerate quicker than ever thought, a matter of decades or less. We have all we need to make these changes—the knowledge, the money, the public will; policymakers remain the only obstacle, thus the need for such direct action. Ocean completes Attenborough’s pivot to activism and is itself a powerful act of protest—although we still might leave the cinema with the lingering feeling of having been entertained by spectacular underwater photography as the world ends.

Anti-protest laws mean that most of the forms of protest undertaken by climate activists over the past six years are now no longer possible—at a time when they are needed more than ever. The type of successful public protests in the 1980s against commercial whaling that Attenborough describes as a beacon of hope in our own fraught times would nowadays be subject to the same laws and restrictions. Many who have exercised their right to protest, in an often eye-catching and creative way, have been silenced by Public Order laws, and served heavy custodial sentences, that have been rightly described by observers as clear contraventions of universal human rights.

Whether delegates to UNOC will have the chance to view Attenborough’s film is unclear. What they will witness is the action planned by Ocean Rebellion, a climate activist group that emerged a few years ago from Extinction Rebellion with the mission to “protect, enhance and repair the high seas”.

Rather than public disruption (delaying traffic, interrupting performances and events, generally annoying as many people as possible for a purpose), Ocean Rebellion directly targets policymaking institutions with images and performances designed to capture media attention. For UNOC, the group is taking a screenprint representing the width of a trawling net, over 150m long—the largest screenprint ever made, it claims—to be unveiled in a performance on the opening day of the conference. On the day of the action, it will be used to “catch” substitutes for the French President, Emmanuel Macron, and EU policymakers, all those who are not measuring up to the demands laid out so clearly in Attenborough’s film.

Ocean Rebellion at the 2022 UN Ocean Conference Photo: © Joao Daniel Pereira

Ocean seduces, disturbs and implores with its unforgettable contrasts of underwater beauty and ruin. It is sure to have some sort of effect on UNOC delegates who happen to see it. Ocean Rebellion will have a more direct impact on the conference, both through the images it has created and those that it provokes in the mass media. In their creativity and urgency, and the risks involved in getting them across, such actions form their own highly compelling species of art.

• John-Paul Stonard is an art historian and author